ANALYSIS: The AKP's great schism

What could normally be observed as a mundane row between two members of Turkey's Justice and Development Party (AKP) now is at the forefront of the debates among Ankara's serpentine wings.

Earlier this week, the tension between the government's spokesperson and Deputy Prime Minister Bulent Arinc and long-serving AKP mayor of Ankara Melih Gokcek, has turned into an exchange of accusations and condemnations when the latter blasted out fiery comments about Arinc's political allegiances.

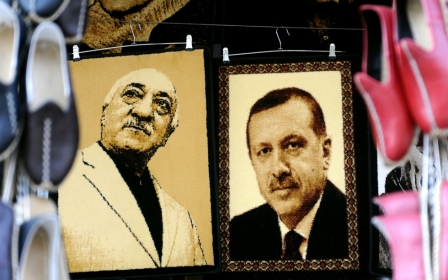

"I always wondered from where they would hit us," said Gokcek on Twitter, implying that Arinc was a Gulen agent. Referring to the alleged conspiracy by now in self-exile US-based cleric Fethullah Gulen to weaken the AKP, the mayor of Ankara denounced Arinc for being a part of Gulen's "parallel structure", calling for his resignation.

Later on the same day, Arinc delivered a strong rebuke during a break in a council of ministers meeting. "Gokcek is corrupt and has no manners," Arinc said, adding that "he sat in the lap of the Gulen movement" and "sold Ankara to this structure plot by plot".

The dispute has come amid ongoing tensions between President Recep Tayyip Erdogan and Prime Minister Ahmet Davutoglu over the government's new steps regarding the next phase of the "peace process" to resolve the decades-old Kurdish issue.

On 28 February, Abdullah Ocalan, the outlawed Kurdish armed group PKK's jailed leader, made an indirect declaration through Kurdish People's Democratic Party (HDP) members and called on the PKK to hold a congress in the spring for eventually laying down arms. President Erdogan expressed his contempt and made clear that he did not approve the establishment of a "monitoring committee". The committee was established to carry the talks between the outlawed PKK and the government forward.

Refusing the involvement of a 5-6 people committee to keep an external eye on the current talks between the government officials and Ocalan, Erdogan said: "These processes are carried out by them [the intelligence agency]. […] If the government is in charge, then the government should continue the process. The process should remain within its [current] framework."

What provoked Ankara Mayor Gokcek to launch such an attack on Arinc earlier this week was the government spokesperson's reaction to Erdogan's meddling in government affairs.

On the establishment of the "monitoring committee" and Erdogan's disapproval, Arinc publicly criticised the president, perhaps in the most open way ever: "Our government regards this step [monitoring committee] an appropriate one. […] It is the government that is running the country and the responsibility belongs to the government."

Though Arinc had to take a few steps back in the aftermath, the row has already become a part of the increasing speculation on just who rules the country.

The cracks in AKP

Upon the election of Erdogan as president in the summer of 2014, AKP's new leader Davutoglu promised to carry Erdogan's fight against the Gulenists forward, and in the meantime he and his new cabinet did their best to keep Erdogan at ease for the upcoming elections in June 2015.

Though both PM Davutoglu and President Erdogan had similar views on the Gulenists, Davutoglu was keen to restore the tarnished reputation of the party in the wake of the corruption probe that shook up the country in late 2013.

He made clear that the "parallel structure" and their fight against them was one thing, but if there really was corruption, those who stepped over their boundaries should be brought to justice. "We are determined to cut off the arms of whoever attempts to embezzle our national resources, even if that is our brother," he said in December 2014.

The first crack in AKP came when the General Assembly of the Turkish Parliament had convened to vote on sending four former ministers to the High Council investigation on corruption charges. This would pave way to the prosecution of the ministers.

Although Davutoglu was in favour of at least doing his part and leaving the matter to the hands of the High Council, Erdogan's repeated calls to acquit the former ministers worked and the parliament denied the request.

This was the first failure of the Davutoglu government over their divergence with Erdogan. The second defeat came when the PM initiated the legislation of the "public transparency package" in February, to increase the accountability of public officials and institutions.

The legislation was postponed till after the elections, when Erdogan held a private meeting with the AKP members in the absence of Davutoglu and reportedly expressed to them his uneasiness.

The third round was different. When Hakan Fidan, Undersecretary of Turkey's National Intelligence Organisation (MIT) resigned and declared his intention to become a member of parliament for the AKP, Erdogan did not hide his disappointment over his decision.

Fidan was the point person to initiate the Kurdish "peace process" in 2008 and then in 2012 under Erdogan's directives. On many occasions, the president referred to Fidan as his "secret keeper".

"If the intelligence agency of a state is insufficient, it is not possible for that state to survive. We appointed him [Fidan] to such a position. I am the one who assigned him. Then... if it [the resignation] was not allowed, he should have stayed, not leave," Erdogan said, showing his frustration.

Though initially Davutoglu seemed to be winning the round by convincing Fidan to join his ranks, a few days later Fidan dropped his candidacy and returned to his original post. Erdogan expressed his gratitude.

Speculation regarding the Erdogan and Davutoglu government split echoed on TV screens and print media. Following the high-profile Fidan ruckus, Erdogan unleashed his anger upon Central Bank President Erdem Basci and Deputy Prime Minister Ali Babacan.

He blamed the duo for being incapable of lowering interest rates, an issue that Erdogan is almost obsessed with, and also he accused them of taking orders from the "interest lobby".

The term "interest lobby" was developed during the Gezi Park protests of summer 2013 by Erdogan's now-advisor Yigit Bulut, for allegedly being behind the demonstrators with the aim of shaking the stability of the government.

It was only after Basci and Babacan's lengthy monetary outlook presentation to the president and Davutoglu's intervention, that waters were calmed, but the downward curve of the depreciating Turkish Lira against the US dollars only slowed down.

According to Murat Yetkin at Hurriyet Daily News, what Turkey is going through is in fact an authority problem. "Whose words should be taken into account to understand what Turkey says: the president or the government? If the president and the government were from different parties, this discrepancy could be understood, but they are of the same party in this case," Yetkin wrote.

However, for some this apparent split is also an outcome of the unsustainability of the current political system. For Yigit Bulut, a staunch supporter of a systemic change, Turkey's first popularly elected president should be bestowed with extended authority.

"The presidency institution no longer represent sthe same post since the election of Erdogan with popular voting. […] The step that should be taken is a transformation to a full presidential system with a focus on leadership," Bulut said.

Super presidency

Erdogan always had the idea of reinstating his executive powers when elected president. However, a systemic change at this level could only be realised by a constitutional change and Erdogan is channelling his energy in AKP's favour with the aim of gathering more support for the next general elections, sometimes at the expense of being criticised for losing his presidential neutrality.

According to Ahmet Tasgetiren at the government-leaning Star newspaper, the election of Erdogan by popular vote has created a sense of duality at the top of the executive branch. "Erdogan is keeping his relationship with the party alive and he wants to use his existing presidential powers," he said. "The current legal structure does not meet the new necessities, and problems arise."

For some analysts, Erdogan's strategy is twofold: on the one hand he is showing his contempt for the "monitoring committee" of the Kurdish peace process, on the other hand he is increasingly criticising the government's measures on the same matter. While the first tactic aims to get the votes of the nationalist electorate, the latter is being perceived as to create a sense of chaos, which would legitimise the systemic change that he is seeking.

According to Ali Bayramoglu at the daily Yeni Safak, even if it is the case, this strategy can only harm the party. "The 'politics of crisis' would only intensify internal party divisions and increase disputes. This would also be reflected on the outer sphere of the government party and government-leaning media," Bayramoglu wrote on Tuesday.

Erdogan's two-fold strategy could work if the AKP's standing in the polls was in favour of granting the party the necessary majority to change the constitution. For Fuat Keyman, professor at Sabanci University international relations department, the "negotiations at the peace process – competition at the election process" tactic does not produce favourable results for the AKP.

"The election outlook is turning in HDP and Nationalist Movement Party's (MHP) favour," Keyman argued. With the addition of other factors that increased the perception of a governing duality at the top of the state, Keyman believes that AKP's strongest side, good economic governance, is now at risk because of the debates on the presidential system.

"AKP still has the power to win the elections, but the probability for acquiring enough votes to change the system is gradually fading away."

Middle East Eye propose une couverture et une analyse indépendantes et incomparables du Moyen-Orient, de l’Afrique du Nord et d’autres régions du monde. Pour en savoir plus sur la reprise de ce contenu et les frais qui s’appliquent, veuillez remplir ce formulaire [en anglais]. Pour en savoir plus sur MEE, cliquez ici [en anglais].