ANALYSIS: Egypt's economy five years after the revolution

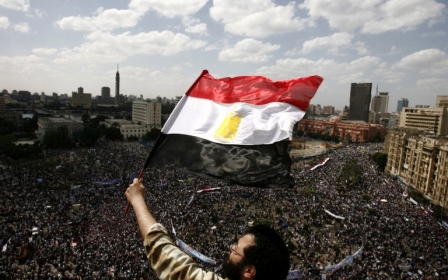

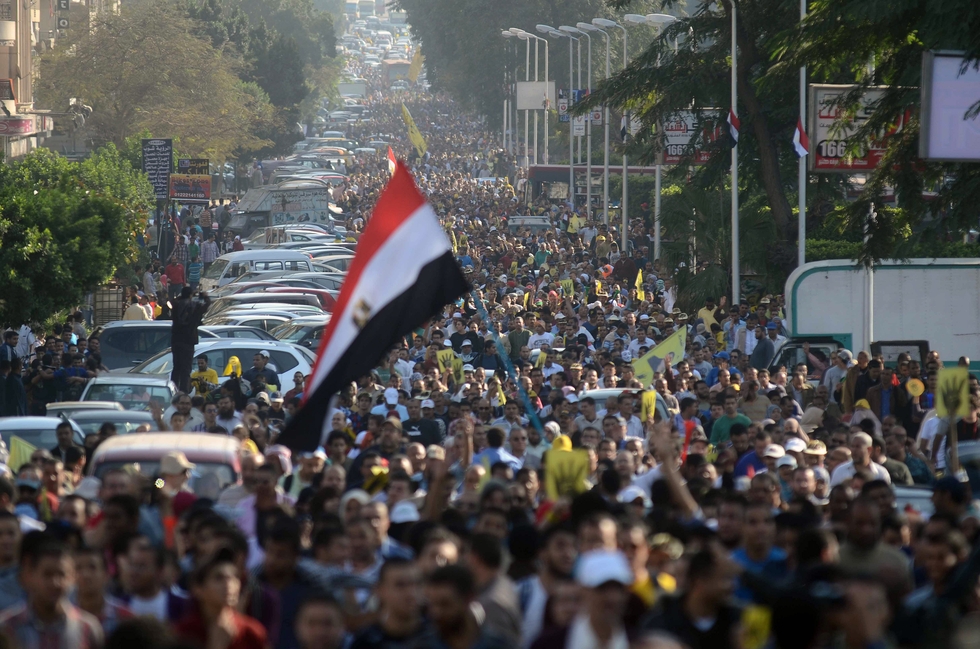

As Egypt marks the fifth anniversary of the 2011 revolution on 25 January, it looks back on five years of rapid political change, social dislocation and economic turmoil. How has Egypt’s economy fared since 2011, and what is the outlook for the next five years?

By numbers alone, on the eve of the revolution, Egypt’s economy looked fairly healthy. During the mid-2000s, growth in gross domestic product (GDP) averaged an impressive seven percent annually. In 2010, the country had accumulated foreign currency reserves equivalent to $35bn (sufficient to cover 8.6 months’ worth of imports) according to the Central Bank of Egypt (CBE), and in the same year GDP per capita stood at $2,600 according to World Bank indicators, an increase of almost 50 percent on $1,400 in 2006.

However, these headline figures masked the fact that the growth was not evenly shared. Much of it was consumption-led rather than investment-led, and concentrated in capital-intensive fields like petrochemicals and energy that tended not to create many jobs. Combined with corruption and red tape, this resulted in a large informal economy – a 2014 study from the Egyptian Centre for Economic Studies put it at two-thirds the value of the formal economy. World Bank figures show that in 2010 poverty rates were running at about 25 percent, up from 16.7 percent in 1999. So while political and social exclusion may have been factors in causing the revolution, economic exclusion shouldn’t be underestimated.

In the aftermath of the revolution, uncertainty over the final outcome led to economic contraction and sluggish growth. Over the past five years, Egypt has shifted through being governed by the Supreme Council of the Armed Forces (SCAF) to president Mohamed Morsi, who was in turn removed by SCAF, and now by President Abdel Fattah al-Sisi. The currency has depreciated and Egypt has required substantial infusions of funding from the international community after imposing capital controls in 2011.

The value of the Egyptian pound (LE) has fallen from LE5.5 to the US dollar in January 2010 to LE7.8 this January, and substantially less on the black market. In November 2015, the CBE reported net reserves of $16.4bn, or 3.4 months’ worth of imports. As a rough measure of international confidence in the Egyptian economy, World Bank indicators show foreign direct investment (FDI) inflows amounted to $4.8bn in 2014, slightly up from $4.2bn in 2013, but far below the $11.6bn of 2007.

Egypt's positive economic sectors

Egypt’s GDP growth rate has fallen but seems to have found a floor since 2011. According to Shanta Devarajan, chief economist for the Middle East and North Africa region at the World Bank: “Growth has averaged in the region of 2-3 percent a year, which is well below its potential and historical growth rates, but impressive given the circumstances. This suggests that there is an underlying core of the Egyptian economy that continues to function, despite everything.”

Indeed, the picture is not entirely negative. According to Brendan Meighan, an economic researcher at the American Chamber of Commerce in Egypt, energy and real estate stand out as two sectors that have performed well over the past five years.

Last August, Italy’s ENI oil and gas company announced it had discovered a gas field in Egyptian waters, the Zohr field, estimated to contain up to 30 trillion cubic feet of gas, enough to make a substantial contribution to the country’s energy needs for decades. While the decline in the value of the currency is a headache for central bankers and importers, it has provided a fillip to some manufacturers, especially those that produce goods without substantial foreign-sourced inputs, as imports have become more expensive while Egypt’s exports are more competitive on world markets.

Massive investment plans that have been in some cases decades in the making are receiving new attention. The Toshka project, a scheme to create a second valley with waters from the Nile along a string of oases in Egypt’s Western Desert, has been renewed. Rechristened the New Valley, it aims to reclaim 1.5 million feddans (a feddan is roughly an acre) of land from the desert at a cost of about $766m.

In June 2015, the presidency said about 500,000 feddans had been reclaimed since work started in 2014, with the remaining million feddans to be reclaimed over the next three years. Perhaps even more ambitious are government plans for an industrial and logistics zone along the Suez Canal known as the Suez Canal Corridor Expansion. This involves building a second canal at a cost of $7.7bn, funded largely from bonds. The project aims to double canal traffic by 2023, increase revenue, expand industrial production and create as many as 1 million new jobs. The first section opened in August 2015. Such projects should stimulate the economy.

Economic reform

The key issue though, is economic reform, which in the case of Egypt cannot be separated from political and social reform. Unemployment remains high. While some measures have been pushed through, including the removal of most energy subsidies in 2014, progress on other measures, including the proposed introduction of a capital gains tax, which has been pushed back to 2017, has been slow. As such, according to Meighan, the mood among the business community is more pessimistic than it was a year or two ago. On the flip side, according to Devarajan, Egypt is making good progress on introducing a Value Added Tax and developing a system of cash transfers for the poorest Egyptians.

In 2015, the World Bank signed a Country Partnership Framework (CPF) agreement with Egypt, under which the bank will assist the Egyptian government in implementing reforms. Broadly speaking, under the CPF, the Egyptian government has committed to improving governance (including tax collection), supporting job creation and setting up a social safety net.

If implemented, these policies would go some way towards restructuring Egypt’s economic system to make it more inclusive. This remains the question for Egyptians in the wake of the revolution and subsequent turbulence. Egypt’s economy is capable of producing growth – it did so under Mubarak throughout the 1990s and 2000s. The challenge is to find a way to produce inclusive growth that benefits all sectors of the population and allows them to participate as full members of society.

A major obstacle to this has long been corruption and cronyism. The Egyptian private sector has been dominated by a relatively small number of large firms that enjoy privileged positions and are able to employ monopolistic practices to generate easy profits. This has suppressed the growth of small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs), many of which remain in the informal sector where they are unable to expand. As such, the private sector has been unable to generate jobs at a sufficient rate to employ the large numbers of young Egyptians who’ve been coming onto the labour market in recent years.

Many of these big companies enjoyed links to the Mubarak family or to the army. On top of companies linked to senior army officers, the Egyptian armed forces themselves continue to own and operate many factories and businesses unrelated to military needs. Taken together, this means the armed forces control much of the economy. How much is unclear, but many sources estimate it at as up to 40 percent. The involvement continues to be opaque, with the armed forces’ budget and accounts secret, and much of the army’s economic activity off the books. So corruption and cronyism continue as factors in the Egyptian economy’s inability to create jobs, and the prevalence of informality and social exclusion.

Political challenges?

In essence then, the key economic challenge for Egypt is in fact a political one. Can Sisi forge a new social contract in Egypt based on an inclusive model that promotes job creation, reduces poverty and creates a realistic social safety net, or will the government return to a business-as-usual model where profits and resources are allocated to well-connected insiders linked to the upper echelons of the armed forces?

From one point of view, the latter doesn’t appear to be much of an option – not only has the government committed with its creditors to introducing reforms aimed at opening access to economic resources and social advancement to more citizens, but Egyptian society, having gone through a revolution, appears unlikely to countenance a backward move after five years of greater political openness.

On the other hand, it is still too early to say whether an army that has been accustomed to playing a substantial role in politics for more than 50 years can commit to withdrawing from economic involvement and confine itself to military activities.

Indeed, according to Shana Marshall, associate director of the Institute of Middle East Studies at George Washington University’s Elliot School of International Affairs, if the army were to dismantle its entire economic apparatus overnight, it is unlikely that it would be able to continue functioning as an institution. As such, the next five years may be as uncertain as the five years since the revolution.

Middle East Eye propose une couverture et une analyse indépendantes et incomparables du Moyen-Orient, de l’Afrique du Nord et d’autres régions du monde. Pour en savoir plus sur la reprise de ce contenu et les frais qui s’appliquent, veuillez remplir ce formulaire [en anglais]. Pour en savoir plus sur MEE, cliquez ici [en anglais].