ANALYSIS: Saad Hariri's resignation shatters hopes of a new Lebanon

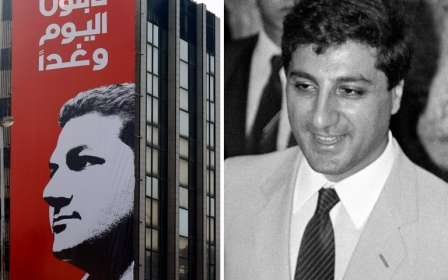

Saad Hariri's resignation as Lebanon's prime minister after just over a year in office sent shockwaves across the country. Politicians, political pundits, and journalists alike expressed their concern for Lebanon's security, stability and economy. To them and many other Lebanese, the resignation was certainly not expected.

Hariri's resignation speech, which was aired live on Saudi Arabia’s Al-Arabiya television channel from Saudi Arabia, focused on Hezbollah and Iran, citing them and a fear for his life as the factors behind his resignation. (His own father, former prime minister Rafik Hariri, was assassinated in 2005.)

His speech was hardline anti-Hezbollah rhetoric that we have not heard from Hariri in years. In fact, just by reading the speech alone, one could assume it was something more likely to be read by Saudi Foreign Minister Adel al-Jubeir.

Moments later, Al-Arabiya reported that an assassination attempt on Hariri "a few days ago" had been foiled. Lebanese Internal Security Forces later dismissed the report, saying it was not factually correct.

Saudi Arabia desperately reshuffles its deck in Lebanon

It is impossible to overlook the geopolitical element in Lebanon, which has been involved in an overt tug-of-war between Iran and Saudi Arabia, and the political developments that led to the election of President Michel Aoun in October 2016 made it clear that there has been a shift in the balance.

An early pointer was the decision by Saudi-backed leader of the (Christian) Lebanese Forces political party, Samir Geagea, to give up his candidacy and to back Aoun (a Maronite Christian). Despite the two men being bitter enemies since the civil war, they celebrated this unity over cake and champagne in what they called the "Christian Marriage".

Then came Hariri's surprise endorsement of Aoun, a move that received condemnation from MPs from his own party, the Future Movement. These two key endorsements led to the Lebanese establishment promoting the government as a consensus or unity government.

Suddenly we saw the fragmentation of Lebanon's "Sunni bloc," where a more-or-less monolithic Sunni political entity spearheaded by Hariri was suddenly divided.

Extremist clerics who previously remained in the shadow of Hariri have now become more empowered, and former Internal Security Forces general and ex-justice minister Ashraf Rifi, who previously resigned from the Future Movement, is growing in popularity for his hardline anti-Iran stance.

In municipal elections in the northern city of Tripoli last May, his independent slate won the majority of seats against a coalition led by Hariri's party, allies, and even pro-Hezbollah parties in the area.

In short, this does not bode well for Saudi Arabia’s interests in Lebanon.

Many see Rifi as Lebanon's next Sunni strongman, and it comes as no surprise that Saudi Arabia has a favourable view of him. He recently visited Riyadh and was the first Lebanese political official to comment on Hariri's resignation on Al-Arabiya.

Away from Lebanon's Sunni bloc is a once-dominant political party now trying to build ties with Lebanese civil society.

The Kataeb Party, founded in 1936 based on the Spanish and Italian fascist parties, has been monitored lately by Saudi Arabia as a potential ally. The Kataeb, unlike the Lebanese Forces and Aoun's Free Patriotic Movement, has only a handful of MPs in parliament and no ministers in the Cabinet.

The party has since dubbed itself as "the opposition," notably trying to rally civil society by leading a week-long protest against a tax increase last spring.

Its third-generation leader, Sami Gemayel, in speeches and news conferences suddenly started to use rhetoric similar to that used by independent protest movements that emerged during the 2015 garbage protests.

This has left many in Lebanese civil society split over whether to cooperate with the Kataeb, a party that actively took part in the 1975-1990 civil war, including the 1982 Sabra and Shatilla Massacres.

In late September, Gemayel flew to Jeddah to meet Crown Prince Mohammad Bin Salman al Saud. Not much was revealed about their meeting, but it won't be their last.

While Lebanese Forces leader Samir Geagea spoke favourably of Hariri's resignation, echoing the concerns the former prime minister had, it is not clear what one can now expect from his Christian political party. At the moment, it enjoys improved popular support and holds some key ministries. However, it has not compromised its anti-Hezbollah rhetoric, so its place in the present state of affairs is not clear.

Elections 2018 postponed?

Despite parliamentary elections originally being scheduled to take place during the summer of 2013, these have been postponed ever since. Last June, the Lebanese government agreed to schedule elections for May 2018, following a settlement on a new electoral law. Hariri's resignation could lead to yet another delay in the elections

With the political circumstances changing, will newly carved-up electoral districts in Lebanon need to be revisited to satisfy the political establishment?

And what about a new Cabinet? This goes beyond the issue of the allocation of ministries or the identity of a new prime minister, which at this point is a complete toss-up. A newly formed Cabinet would function for six months at most by the time elections are scheduled to take place.

Security fears going forward

Four days prior to Hariri's resignation and after a meeting with him, the Saudi Minister of State for Gulf Affairs, Thamer al-Sabhan, tweeted that the two agreed on "many things that are of interest to the Lebanese people … ". Following Hariri's resignation, he tweeted simply: "The hands of treachery and aggression must be amputated," clearly a reference to Hezbollah and Iran.

The absence of a Cabinet definitely throws a wrench into the cogs of the Lebanese government machine.

Discussions of internal strife and violence have already loomed, and opponents of Saudi Arabia have accused the kingdom of trying to create instability in Lebanon.

But there is also the Israel factor. Since the election of Aoun, a key ally of Hezbollah, as president, Israel's pro-war rhetoric against Lebanon has heated up. The common theme is that the Lebanese state and Hezbollah are now one.

Israeli Education Minister Naftali Bennett has been among the most outspoken of Israeli officials. In early April, he published a column in The Times of Israel titled "Hezbollah is Lebanon is Hezbollah," and based on that logic said that Lebanon as a whole should be fair game if a war broke out.

After Hariri ended his second stint as prime minister (he previously held the post for about 18 months from 2009 to 2011), Israeli officials were quick to share their two cents.

Former justice minister Tzipi Livni, an Knesset member in the Zionist Union Party, tweeted that this only confirmed that terrorist organisations, citing Hamas and Hezbollah, should not participate in elections.

Resignations of Lebanese prime ministers are not uncommon; it is the circumstances - local and regional - surrounding the shock of Hariri's decision to quit that is a cause for concern locally.

When Aoun was elected as president, the political alliances were widely seen as opening a new chapter in Lebanon's history. Strangely, there was little discussion of the possibility that this "breakthrough" would simply backfire and the country would revert to a more intense or hostile political environment - as is the case now.

Middle East Eye propose une couverture et une analyse indépendantes et incomparables du Moyen-Orient, de l’Afrique du Nord et d’autres régions du monde. Pour en savoir plus sur la reprise de ce contenu et les frais qui s’appliquent, veuillez remplir ce formulaire [en anglais]. Pour en savoir plus sur MEE, cliquez ici [en anglais].