ANALYSIS: Fall of Istanbul's mayor creates prize job for Erdogan loyalists

ISTANBUL, Turkey – Through sheer size and population alone, Europe’s largest city Istanbul holds the political destiny of regional power Turkey in its hands. And being its mayor is a prestigious and demanding job.

One of those demands now appears to be complete loyalty to the president.

Kadir Topbas, Istanbul mayor for 13 years, resigned late last month. No reasons were given, nor was it clear whether it was a forced resignation.

His decisions as mayor of such a large city for such a long period naturally brought an equal number of supporters and detractors.

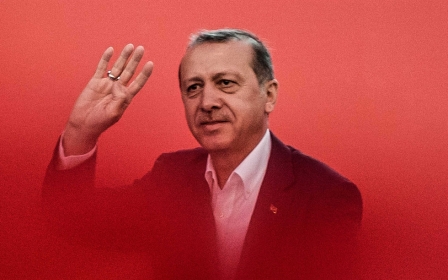

But his fall from favour in the eyes of the Turkish president, Recep Tayyip Erdogan, began after the failed coup attempt last July, and that disdain toward him has since often been on public display.

Even during the lowest ebbs in Turkish democratic history there is no precedent for a politician forcing an elected mayor out of office

- Ali Bayramoglu, Turkish commentator

Ali Bayramoglu, a veteran commentator and journalist on Turkish politics, told Middle East Eye that even though Turkey has never had a fully functional democracy, it had never seen such levels of arbitrariness to date either.

“Even during the lowest ebbs in Turkish democratic history there is no precedent of a politician forcing an elected mayor out of office. This is Tayyip Erdogan asserting his personal hegemony on the party by forcing Topbas to resign,” said Bayramoglu, who believes he was definitely pushed out.

The first questions over Topbas’ loyalty to Erdogan began being asked in the pro-government media when it was discovered that he was in New York attending a conference on the night of the coup attempt. His failure to arrange a return for another two days invited more scorn.

Then it was reported that Erdogan gave him a public dressing down after he was late to arrive at a funeral being held for one of the victims of the coup attempt on 17 July.

Erdogan reportedly, in a rare move, openly said “…the mayor has finally arrived. My eyes were searching for you."

At most public ceremonies in Istanbul since, the mayor was no longer seated next to Erdogan but was relegated to the fringes instead.

The fact that Topbas’ son-in-law was also arrested - in September 2016 - for allegedly being a Gulenist led to even greater questioning of his loyalty to the president by media closely aligned to Erdogan.

Gulenists are supporters of Fetullah Gulen, a Turkish preacher based in the US, and who authorities hold responsible for infiltrating the state apparatus and orchestrating last July’s coup attempt.

Like most members of the ruling Justice and Development Party (AKP) who have left or been pushed out of the party, Topbas, too, refused to publicly voice any criticism.

Upon resignation, he simply said he would now dedicate his life to serving “Islam and humanity” and didn’t provide a reason for standing down.

Internal cleanout

Following the April referendum, Erdogan immediately made clear that he would launch a clear-out of the AKP after retaking the chairmanship of the party.

The referendum, narrowly endorsed by 51.4 percent, was a vote on replacing the country’s parliamentary system with an executive presidency. It also permits Erdogan to be both president and party chairman.

It is this dual role that is a major problem, according to political observers.

“The image of a party-state is created when the president also gets to be a leader of a political party. The president uses the powers of that office in the party as well for personal gain,” said Bayramoglu.

The AKP has always prided itself on being able to revitalise and refresh its ranks. But such changes in the past haven’t been as cantankerous or full of public rebuke.

On many occasions Erdogan has said that “anyone not adhering to the line would be discarded” and has invited party officials at both local and national level to “resign before being forced out”.

Elections slated for 2019 - local, parliamentary and presidential - are critical for the AKP and Erdogan.

The presidential poll in particular is vital because Erdogan will need at least 50 percent of the vote to get hold of the super presidency.

To Bayramoglu, a lot of Erdogan’s arbitrary actions regarding local and provincial offices of the party are down to his fear of the impact local elections could have on his run for the presidency in 2019.

“The local elections will come first in March 2019. Comprehensive victories for the AKP will smoothen Erdogan’s path for the presidential election. But losses could badly affect his chances,” said Bayramoglu.

“He is using his presidential powers to arbitrarily make changes within the party structure.”

With a distinctly mixed record on economic and foreign policy, the AKP needs to fall back on what it has always claimed as distinguishing it from rival political parties: its closeness to the public and the provision of public services.

Erdogan’s strong emphasis on local administrations and municipalities is with that in mind, officials have privately told MEE.

He is looking to counter a growing perception that the AKP, too, is losing touch with the public after 15 years in power.

'He is using his presidential powers to arbitrarily make changes within the party structure'

- Ali Bayramoglu, Turkish commentator

Flashy displays of wealth and luxury by many with close links to AKP officials in recent years has caused a backlash against the party. There have also been increased grumblings, in the public and in the AKP itself, about rampant cronyism, nepotism and corruption in the party’s ranks.

Apart from Istanbul, there have already been a few “resignations” from local and provincial AKP-controlled administrations. Local media reports suggest more are to follow in the coming months.

Mahir Unal, the AKP spokesperson, on Tuesday denied reports about mayors being asked to resign.

“Statements saying this or the other mayor has been asked to resign do not reflect the truth. We are evaluating all our municipalities. Performance-related criteria are being researched,” said Unal.

Erdogan himself, when asked if he had demanded the Ankara mayor’s resignation, told reporters on Tuesday: “There is nothing [demand for resignation] now but that doesn’t mean there won’t be in the future.”

The results of the April referendum appeared to come as a shock to Erdogan and the AKP, both of whom probably expected a far larger margin of victory.

Losing Istanbul means losing Turkey

Of particular concern was that most of Turkey’s urban centres, including Istanbul, voted against Erdogan’s and the AKP’s executive presidency project.

The significance of Istanbul is not lost on Erdogan, who launched his own political career in the megapolis and attained fame after being elected mayor of the city in 1994.

On 24 September, in a speech at an AKP meeting in Istanbul, Erdogan’s message was blunt.

“If we lose Istanbul, we will lose Turkey,” he was reported as saying.

Neither of Topbas’ two deputies were nominated to stand for mayor until the 2019 elections. Erdogan nominated Mevlut Uysal who was elected as mayor on 28 September.

Uysal, an Erdogan loyalist, was mayor of Istanbul’s Basaksehir district, one of Istanbul’s outlying districts with a more conservative leaning.

Uysal, however, is not a certainty to be the AKP’s pick for the 2019 local election. He will reportedly be given until 2019 to prove himself.

The promise of being put forward for the prestigious but relatively less political - than a ministerial position - job of Istanbul mayor is also being said to be used by Erdogan as a bargaining chip to reward loyalty to both current and former party heavyweights in return for complete backing in the run-in to the 2019 presidential elections.

One name in the corridors of power in Ankara being touted for that position is that of former president, Abdullah Gul.

It was said that Erdogan’s team is preparing such an offer to heal the rift that has emerged in the AKP between the more hawkish pro-Erdogan and more dovish pro-Islamist camps. Neither side has publicly commented on it.

Another name mentioned for future Istanbul mayor was that of Prime Minister Binali Yildirim, an unequivocal Erdogan loyalist. He will be out of a job once his position is scrapped after the 2019 elections.

Yildirim played down that suggestion but did not outright deny such a possibility in the future when asked about running for Istanbul mayor in 2019 during a televised interview.

“That position is vacant now but someone will fill it. Where are you going to put me? That position is filled. Good or bad, I still have a job here,” said Yildirim.

Middle East Eye propose une couverture et une analyse indépendantes et incomparables du Moyen-Orient, de l’Afrique du Nord et d’autres régions du monde. Pour en savoir plus sur la reprise de ce contenu et les frais qui s’appliquent, veuillez remplir ce formulaire [en anglais]. Pour en savoir plus sur MEE, cliquez ici [en anglais].