How Jordan brought its economic woes on itself

As protests continue in Jordan, the kingdom has put the blame for the economy’s lacklustre performance and controversial tax reforms on IMF-backed austerity measures and a drop in foreign aid.

But in reality, say analysts, the economy has been badly managed for decades, while significant amounts of government spending remain undisclosed.

'The problems were there long before the refugees arrived or Emirati money fled'

- Pete Moore, associate professor at Case Western Reserve University

A quick look at headline figures explains what sparked protests over the imposition of a new income tax and price hikes and has sustained them over a week despite the resignation of the government and the prime minister.

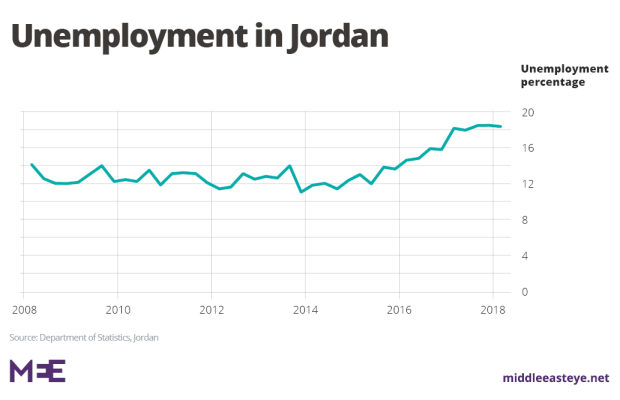

According to department of statistics data released this week, unemployment has hit a 25-year high at 18.4 percent, rising to 24.1 percent among university graduates – and these estimates are conservative.

On top of that, inflation has doubled since 2006, raising the cost of everyday goods. At the end of May, the Economist Intelligence Unit declared Amman the most expensive city in the Arab world and 28th worldwide.

Trade unions say the minimum wage of JD220 ($310) per month is a third less than what’s needed to eke out a living.

King Abdullah told the press on Monday that there had been a “failure and slackness on the part of some officials regarding decision-making”, and “the world has not fully shouldered its responsibilities” by reducing aid despite the kingdom hosting close to a million Syrian refugees.

He also conceded that the tax reforms, a condition of the IMF that has been pending for years, had been badly communicated to the public. Gulf states had been major donors to Jordan over the years, but have scaled back funding, notably neighbouring Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates.However, experts say the cause and effect that has impacted Jordan's economy is a bit more complicated.

“All the policies taken by Jordan they were not forced to do. They live in a tough neighbourhood, true, and have a lot of (Syrian) refugees, but all that said, the problems were there long before the refugees arrived or Emirati money fled,” said Pete Moore, associate professor and director of graduate studies at Case Western Reserve University in the US.

“An important part of the narrative is that it is self-inflicted by the Jordanian political elites.”

Confusing cause and effect

It’s true that aid to Jordan has dropped. Foreign grants, equivalent to 2.5 percent of GDP, declined by 15 percent year-on-year in 2017, according to Standard & Poor’s.

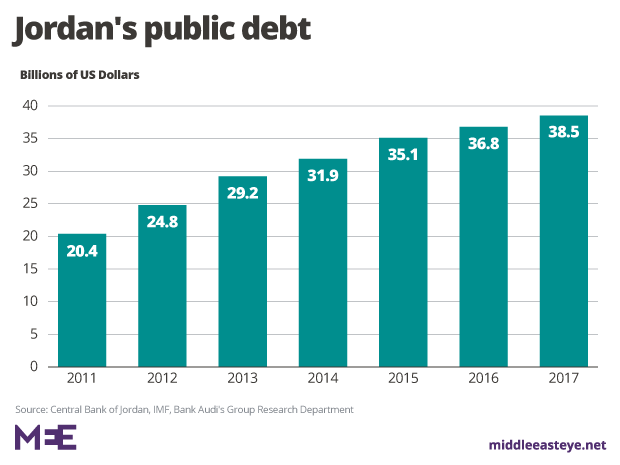

Meanwhile, the country has had to go to the international money markets for debt financing, which has surged from 67.1 percent of GDP in 2010, to 95.9 percent of gross domestic product (GDP) in 2017, according to Capital Intelligence Ratings. International borrowing has gone from three percent of central government debt in 2012, to 21.9 percent in 2017.

“The royal court is trying to make it look like the IMF, or the Saudis or Emiratis are pressuring Jordan, but this confuses cause and effect,” Moore said.

“The cause is primarily linked to the royal court’s policies since the 80s, to a massive military build-up under King Hussein. In per capita terms, the regime has basically shunted money towards the military and obscured money spending, one of the main drivers of the socio-economic crisis.”

According to the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute (SIPRI), in 2017 the military accounted for 15.8 percent of government spending and 4.8 percent of GDP, one of the highest in a region that has some of the highest military spending in the world.

While officially budgeted at $1.87bn, with some $350m a year funded by the US, the total amount spent by the armed forces, the General Intelligence Directorate (GID) - the country’s mukhabarat – and the royal court is not disclosed. So secretive is military spending that there is not even a defence ministry.

It’s this lack of transparency that has made austerity measures and tax increases hard to swallow for many Jordanians, said Ziad Abu-Rish, a professor of Middle Eastern history at Ohio University and co-editor of Jadaliyya, who is also Jordanian.“The argument that there is a budget deficit and you have to cut spending makes it sound more innocent than things are. We don’t know what the budget actually looks like to determine if these are the necessary cuts as we’ve very little sense of what percentage of the state budget the military and royal institutions represent, and how that money is being used. And I should be clear: we as Jordanian citizens are discouraged from discussing these things and sometimes criminalised,” Abu-Rish said.

“So the idea of cutting a safety net at the same time as increasing unemployment and poverty, and a decrease in purchasing power, makes no sense as far as the population is concerned,” he said.

Mixed bag of reforms

While military spending has remained high, spending on socio-economic issues has dropped. So too have sources of government funding after Jordan implemented a raft of economic reforms in the early 2000s to be in line with the promotion of free trade and neoliberal policies by the World Trade Organisation (WTO), the World Bank and the IMF.

Customs duties had been one of the biggest government revenue earners, but were resultantly slashed, while tax-free policies to attract foreign investment also impacted the country’s budget.

He also pointed to the free trade zones established in the early 2000s that are tax exempt and the Qualifying Industrial Zones that manufacture $1.3bn worth of garments a year but are majority-owned by southeast Asian firms, while out of the 56,000 people employed in the sector, just 30 percent are Jordanians.

Furthermore, there are 800,000 migrant workers in the country – just less than 10 percent of the population - which benefits employers and small businesses because of the low wages, but does not reduce unemployment, said Tariq Tell, a Jordanian professor of politics at the American University of Beirut.

Tell added that the country’s banking sector is owned by Saudi interests, which runs the public debt, while one of the country’s largest foreign currency earners, the phosphate industry, was privatised, depriving the kingdom of long-term income.

Punishing the middle class

What is particularly noticeable about the protests is that unlike in the past, the current demonstrations have been spearheaded by professional syndicates and involved the middle classes.

“The new tax law would squeeze people on JD 1,000 ($1,410) to 1,500 ($2,100) a month, while the business class is basically paying no tax. There are many loopholes that could be closed, but instead the middle class are being punished, which is why they are mobilising,” said Tell.

'There’s a sense of mismanagement of funding coming through to the country, yet they’re taxing the poorest?'

- Liat Shetret, senior adviser at Global Centre on Cooperative Security

Behind the protesters' calls to freeze the tax reforms is anger at corruption, cronyism and fiscal mismanagement. “The protesters' claim of corruption being a core issue is quite accurate. There has been a lot of money going in and out of Jordan, whether Iraqi capital, development aid, or American money, and a lot of it has not benefited everyday Jordanians,” said Moore.

Jordan was ranked 59 out of 180 countries in Transparency International’s 2017 Corruption Perceptions Index. “People believe there is widespread corruption, and that Queen Rania’s family is corrupt,” said Tell.

Unless such corruption is cleaned up and there is more budgetary transparency, increasing taxes – no matter how needed to balance the books – will be a hard sell.

“The Jordan government handles donor relationships, but it is not as coordinated as it could be. The concern is that there’s no visibility around which programmes are being implemented, and that donor money can be duplicative.”

Who is accountable?

In the immediate term, the new cabinet is considered a deflective manoeuvre to shift the blame away from the monarchy.

“For 25 years, each different government claims it will reform the economy, so if we’ve the highest unemployment in 25 years, such reforms have been a complete failure, and who is accountable for that?” Abu-Rish said.

“We need to acknowledge there is a monarchy that has overwhelming concentration of political power, and a cabinet can come and go at the will of the king. It was the royal court that decided who was in cabinet, and it brought in (prime minister) Hani al-Mulki and his group in, and brought them out, and is now bringing a new group in.”

'For 25 years, each different government claims it will reform the economy. So if we’ve the highest unemployment in 25 years, such reforms have been a complete failure, and who is accountable for that?'

- Ziad Abu-Rish, professor at Ohio University and co-editor of Jadaliyya

The incoming cabinet is the seventh since King Abdullah came to power in 1999, and the second since the king dissolved the parliament in 2016.

The new prime minister, Omar Razzaz, is a Harvard-educated former senior World Bank official. It is expected that he will pursue a similar economic strategy to previous governments.

Bottom line, said Riad al Khouri, Middle East director at political risk adviser GeoEconomica GmbH in Amman, is that Jordan is heavily in debt because of corruption and inefficiency.

“Will all these problems be solved by the new prime minister? No. The measures he will introduce will be the same,” he said, adding, “I think this income tax law will pass but instead of being introduced en bloc will be done piecemeal, and not shoved down the throats of the public.”

This article is available in French on Middle East Eye French edition.

Middle East Eye propose une couverture et une analyse indépendantes et incomparables du Moyen-Orient, de l’Afrique du Nord et d’autres régions du monde. Pour en savoir plus sur la reprise de ce contenu et les frais qui s’appliquent, veuillez remplir ce formulaire [en anglais]. Pour en savoir plus sur MEE, cliquez ici [en anglais].