ANALYSIS: Jordan struggles to keep economic fires burning

Following last week’s parliamentary elections, Jordan’s King Abdullah on Sunday made his priorities clear when he asked Hani al-Mulki, formerly the country’s caretaker prime minister, to form a new government with a focus on economic growth, introducing reforms and diversifying the economy.

The kingdom is one year into Jordan Vision 2025, a 10-year blueprint for economic and social development. The plan is based on two scenarios: that Jordan’s economy will grow by 4.8 percent or even 7.5 percent over the decade.

But both figures are a long way off for a country with a stagnating economy and few resources besides its strategic location. There’s no oil, and despite a wealth of sunshine, little solar energy. Jordan is the world’s second water-poorest nation, making agri-business challenging and expensive.

Exports centre around potash, phosphates and labour. Despite importing a third of its domestic labour force, Jordan exports 40 percent of its workers abroad. They bring in around $3.8bn worth of remittances into the country, which make up at least 20 percent of GDP and, according to analyst Fahed Fanek, provide a vital monthly income for around 350,000 families.

A vibrant private sector might make up for national financial shortcomings, but Jordan’s largest employer is the state. Excluding the military, Jordan’s large public sector employs 13 percent of the workforce to the cost of 37 percent of GDP. Although they are widely seen as a career-long ticket to security, state jobs pay poorly: the average public sector paycheque puts a single-income family of four below the poverty line.

With bare cupboards at home, Jordan has long relied on tourism, foreign direct investment and hefty US budgetary aid. But the flow of foreign money into Jordan is slowing.

According to government statistics, foreign direct investments dropped by 35 percent in 2015, while exports declined by 10 percent. Tourism has also crashed due to the wars in neighbouring Syria and Iraq. Revenue for Jordan’s most crucial industry sector dropped 12 percent in the first quarter of 2015, and has fallen since.

With less money coming in, spending is down. This past Eid al-Adha, typically a time when families buy new clothing for children, saw Amman shopkeepers report their lowest sales in a decade.

Compounding this, heavy taxes on imported garments are giving shoppers pause, causing the retail sector to contract. Despite sales tax on international brands being halved in late 2015, more than a few have left Jordan for better profits elsewhere.

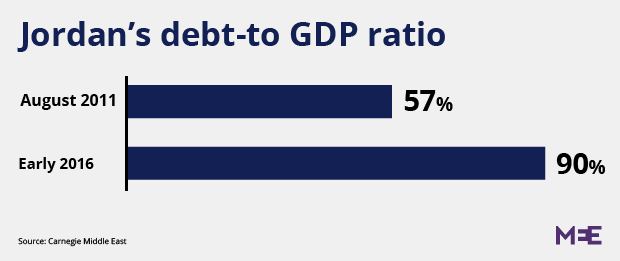

Jordan has borrowed heavily to compensate. According to a March 2016 Carnegie report, Jordan’s debt-to-GDP ratio raced from 57 percent in August 2011 to 90 percent in early 2016. Public sector overspend was a significant element, particularly losses incurred by the state’s water and electricity authorities.

Despite a healthy inflow of UN aid, the cost of hosting around a million Syrian refugees has also hit hard: during the time, the country’s absolute debt more than doubled.

Papering over the cracks

In January, Jordan’s Lower House of Parliament passed a new budget bill, designed to decrease public spending. The bill came hot on the heels of a desperately needed International Monetary Fund (IMF) loan of nearly $800m. The loan comes with strings attached: fiscal reforms, structural adjustments and measures to employ more youth and women, who make us just 13 percent of the labour market.

But economists caution of deeper structural concerns.

Subsidies, which accounted for nearly 9 percent of Jordan’s GDP over the 2011-2012 period, top the list.

More than a third of Jordanians live below the poverty line. The minimum wage, 190 JOD /month ($150) is less than half the poverty threshold for a family of five. Subsidised electricity, water, bread and petrol keep Jordan’s poor afloat, but economists say the implementation is not working.

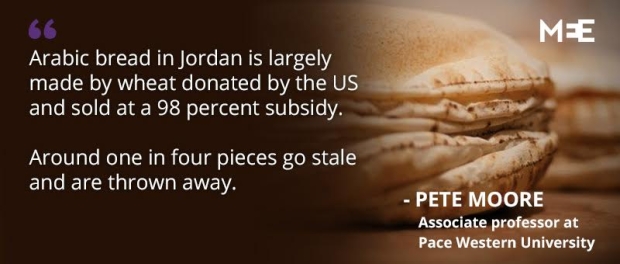

“Jordan has tried to target subsidies but they’ve failed because of the terrible administrative capacity resulting from a long-term decline in the Jordanian state. It’s bankrupt,” said Pete Moore, an associate professor at Pace Western University.

He pointed to Arabic bread, sold at a 98 percent subsidy, as one example: made with wheat donated by the US as aid, Arabic bread represents one of the great wastes of the Jordanian economy. Around one in four pieces go stale and are thrown away.

“I think the economy is the worst it has been in the 20 years I have been going to Jordan. Per-capita income hasn’t budged since the mid-80s, and we are now seeing real, genuine unemployment among the young and upwardly mobile,” said Moore.

Amman: Tale of two cities

In June, Jordan’s Centre for Strategic Studies polled 1,800 Jordanians and 700 “opinion leaders” about their views of the government formed when the country’s parliament reach the end of its term in late May and King Abdullah named Hani Malki caretaker PM.

Some 45 percent of the national sample and 56 percent of opinion leaders thought Jordan was in worse shape now than a year ago.

In Amman the situation looks particularly grim. Jordan’s capital has long been two cities: glossy west Amman for ex-pats and the handful of wealthy Jordanians, and gritty east Amman for everyone else. But west Amman is slowing down.

“Three years ago, my customers were tourists, wealthy Jordanians, and ex-pats. Now, it’s just the ex-pats,” said the owner of an upscale bath products shop in Amman’s touristy Rainbow Street.

Moore said the real estate and insurance industries used to paper over the crisis in west Amman, but these bubble have now burst.

“We’re really hurting,” said the Jordan head of an international consultancy, who didn’t want her company’s name in the press.

“Business is down, people are slow to pay, some clients aren’t paying at all. It has always been tough in Jordan, but this is the most difficult it has ever been.”

Competition for a dwindling supply of jobs has grown fierce. One manager of a media company, who asked for his business not to be named, told Middle East Eye that when he placed an advertisement for a secretary, he had more than 300 calls in five days.

“I made the mistake of putting my own phone number in the ad, I had calls day and night,” he said.

Three years ago, a similar ad for a low-paying secretarial job netted a dozen CVs and one hire. This time, he got calls from family members begging him to hire their sisters, and offers from Syrians who said they would work for a third of what he might pay a Jordanian.

But the numbers masked a bigger problem: few candidates, he said, were qualified.

“You rarely find IT skills and proficient English because the universities here don’t prepare students for the market. Education is very poor in Jordan,” he said.

For a long time, remittances allowed families to hire private tutors to help but this too has now ground to a halt.

Security doesn’t come cheap

The recent string of security incidents in Jordan, beginning with a shooting at a police training academy outside Amman in November 2015, has underscored, for locals and international backers, the importance of keeping Jordan stable in a fast-destabilising region.

According to Moore, the US was projected to donate an unprecedented $900m to Jordan’s military this year. Here, Jordan has a trump card: for allies and regional partners, the spiralling cost of security is an acceptable price to pay given its strategically key location. The EU wants refugees to stay in Jordan. Israel wants a strong fence between it and the Islamic State. The US and the UK want a base where they can maintain a military presence.

Jordan’s military is growing into the outsize role its geography offers. Forces are getting better – and costlier – training and equipment than ever before, thanks largely to US and UK funding and hands-on support. The number of men in uniform is also climbing: official data shows a 10 percent increase over the past two years. US economic and military aid to Jordan has risen to $1.275 billion during 2016, with hundreds of millions more for border security and anti-terrorism.

Jordanian economist Riad al-Khouri believes this marks a dangerous dependency for the state.

“One in four male members of the labour force works for the government and carries a weapon. This makes them the bedrock of the system, and they are paid and massaged accordingly,” he said.

That massaging, he said, includes healthy pensions, pay bumps and promotions, as well as access to co-ops where family members can by buy groceries at cut prices.

All of this, and what he describes as a wealth of “corruption, back-handers and side contracts obtained through family or tribal connects” keeps the Jordanian government stable, he said. Like Moore, Khouri described a donor-fed system designed to shore up power rather than propel economic growth.

But have we reached a breaking point?

The IMF has demanded fiscal reform and the rolling back of subsidies for its support. The last time the bank pushed for this in 2012, angry Jordanians took to the streets.

The EU has also gotten involved and a new deal, described by Moore as “incredibly clever and evil,” has relaxed trade rules with Jordan for manufacturers that employ Syrians, part of an EU strategy to stem the tide of asylum seekers by improving their lives in Jordan, Lebanon and Turkey. Yet the economist predicts that due to endemic corruption and the quickening rot of the Jordanian state, any foreign re-boot plan is likely to fail.

The general economic decline, mirrored by a rise in military spending and a spike in economic criminality, bodes badly, he explained.

“The question is whether it’s going to continue to be a slow decline, or become much more rapid and unpredictable,” said Moore.

“If it’s slow, they can keep their hands around it. But wider unrest, losing control of parts of the country, that’s the beginning of things they really can’t get a handle on.”

This article is available in French on Middle East Eye French edition.

Middle East Eye propose une couverture et une analyse indépendantes et incomparables du Moyen-Orient, de l’Afrique du Nord et d’autres régions du monde. Pour en savoir plus sur la reprise de ce contenu et les frais qui s’appliquent, veuillez remplir ce formulaire [en anglais]. Pour en savoir plus sur MEE, cliquez ici [en anglais].