ANALYSIS: Rising Saudi death penalty targets most vulnerable

Saudi Arabia is on course to execute record numbers of people in 2015, as human rights groups warn that migrants and poorer Saudis - who make up the vast majority of those put to death - are struggling to access justice.

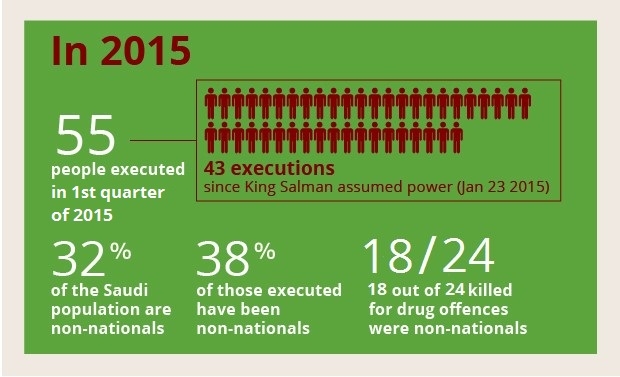

According to figures released by the Ministry of Interior, 55 people were executed in the oil-rich kingdom in the first quarter of 2015, nearly two thirds of the total executed the previous year.

The dramatic increase in corporal punishment comes as analysts continue to express concern over the independence of the judiciary and access to justice for those near the bottom of the socioeconomic ladder.

Eighty-three people were put to death in 2014, the highest number in five years. This "unprecedented spike" in executions, according to Amnesty International, has continued into 2015, despite initial optimism after the accession of King Salman bin Abdul-Aziz in January.

Saudi Arabia enforces the death penalty for rape, murder, apostasy and drug trafficking. Executions are usually carried out by beheading in public spaces.

“We are at shocking levels,” says Adam Coogle, a Middle East researcher for Human Rights Watch who focuses on Saudi Arabia. “Typically Saudi Arabia executes somewhere between 70 and 90 people annually. But at the moment we are on pace for at least 200 this year.”

The figures also show that Saudi authorities execute a disproportionate number of foreign nationals, amid ongoing concerns over access to justice for non-Saudi citizens, especially those who speak little or no Arabic.

Migrant access to justice

Migrant workers and non-nationals make up around 32 percent of the Saudi population, according to the latest government estimates published in 2013.

However, figures from the first quarter of 2015 show that over 38 percent of those executed so far in 2015 were non-nationals, many of them from the poorest countries in the region like Yemen, Pakistan and Syria.

There was international outcry in January 2015 when authorities publicly executed a Burmese woman, Laila Bint Muttalib Basim, in the holy city of Mecca. Many were shocked by leaked footage showing the woman continuing to protest her innocence as she was struck three times by the executioner’s sword in a busy suburban street.

“There are recurring complaints about the quality of justice for non-Saudis, and especially non-Arabic speakers,” says Coogle. “There are translation issues and problems with the reliability of translators. Migrant women working in Saudi Arabia who spoke to Human Rights Watch complained that, when they ended up in court over employment matters, they simply had no idea what was happening.”

Another issue, explains Coogle, is that many non-Saudi nationals on lower incomes struggle to access quality legal representation. “Non-nationals can theoretically access lawyers, but it’s an issue of resources. If you’re a poor migrant worker you can barely pay your rent.”

“Some Saudi lawyers take on these cases for free, but there’s no systematic effort.”

Fair trials evade Saudi’s underprivileged citizens

Access to justice is an issue not just for non-nationals, but also for poorer Saudi citizens, according to Radidja Nemar, a legal officer specialising on the Gulf with Alkarama, an independent Geneva-based human rights monitor.

“Most of the Saudi nationals who are executed are from socially disadvantaged backgrounds and cannot afford a proper defence lawyer,” explains Nemar.

She cites the case of seven men executed in 2013 for armed robbery at a series of jewellery stores in Abha, a large city in south-eastern Saudi Arabia.

The gang’s ringleader was crucified over the course of three days, while the others were shot by firing squad in a public square.

The trial of the seven men consisted of three brief court sessions without the presence of a lawyer. The men were also severely tortured in prison, subjected to sleep deprivation, and reportedly given hallucinogens with their food.

Several human rights groups had appealed to the UN to halt the killings, saying the men had no legal representation - but the UN did not act quickly enough.

In a last message, conveyed to Alkarama just days before their execution, the men confessed to the robbery but questioned the severity of the sentence against them.

“We did not kill anyone,” the message read. “We are poor people and we have no one to defend us. It is true that we stole several thousand riyals, but the members of the royal family are stealing billions of riyals, and no-one has ever held them accountable for that.”

Nemar explains that, under Saudi law, the crime of the seven did not necessarily merit execution since the accused did not intend to kill. However, she says, judges have “a lot of leeway” to apply the death sentence in these kinds of discretionary cases, where the Islamic legal system does not prescribe a specific punishment.

“Basically if you end up with a severe judge then you are at greater risk of being subjected to a death sentence.”

Many have questioned a system that gives individual judges so much power, especially since the Saudi prosecution service falls under the remit of the Ministry of Interior rather than the Ministry of Justice.

This system, says Coogle, is “unlike almost any other country in the world,” and leads to a “problematic image” regarding the impartiality of the Saudi justice system.

Waleed Abulkhair, the high-profile Saudi lawyer who was charged with “inciting public opinion” under the kingdom’s anti-terrorism law and sentenced to a 15-year prison sentence in 2014, alleged that the country’s judiciary is not independent.

Non-violent drugs offences

So far in 2015 most of those executed in discretionary cases, in which the judge decides on the punishment, have been put to death for non-violent drug offences, figures show.

43 percent of those executed overall in 2015 were for smuggling drugs ranging from heroin to marijuana.

The vast majority of offenders in these kinds of cases are non-Saudi nationals – of 24 executions for drug smuggling in the first three months of the year, 18 of them were for non-Saudi citizens.

“It’s by far and away foreigners [who are executed for drugs offences in Saudi Arabia],” explains Coogle, who says that he fears that many of those put to death are not ringleaders of criminal gangs but simply “mules who are pressured into [smuggling], as we see across the world in the drugs trade".International human rights law does not prohibit execution, which is practiced across the globe. Amnesty International reported on Wednesday that an “alarming” number of countries worldwide resorted to the death penalty in 2014 in what it called “a flawed attempt to tackle crime, terrorism and internal instability”.

However, key international treaties demand that countries carry out executions only in the most serious cases.

“It is certainly debatable whether or not Saudi Arabia does reserve executions for the most serious cases,” according to Coogle.

This, he says, combined with what he calls an “assault” on freedom of speech in recent years, makes a “mockery” of Saudi Arabia’s membership of the UN Human Rights Council.

“When you become a member of the Human Rights Council you are supposed to uphold the highest standards of human rights. It’s obvious that KSA hasn’t done that over the past few years, and the fact that many of these abuses are actually getting worse is very troubling.”

Pressure on Saudi unlikely

Human rights organisations frequently criticise decisions made by Saudi judges, particularly as the rate of executions appears to be increasing.

However, putting pressure on Saudi Arabia to end its blatant human rights violations is made harder by the cosy relationship it enjoys with powerful Western nations.

A key ally of the United States, the Gulf kingdom is shielded from accountability in order to maintain the status quo both regionally and domestically, researchers say.

Saudi Arabia recently became the world’s largest arms importer, while the US is thought to be the second largest exporter - US arms sales to the kingdom were worth over $5.5 billion in 2013 alone.

Many doubt whether the US, itself the world’s fifth most prolific executioner, would jeopardise such considerable business interests in the kingdom by pressing Saudi Arabia on its rights record. Last month Sweden cancelled a lucrative arms contract after a very public spat over human rights, sparking anger among many in the Swedish business community.

However, said Nemar: “It’s not just about business ties and oil. It’s also about international security. Saudi Arabia is a key part of all of the strategies that the West tries to [implement] in the Middle East.”

Even if change were to come from outside, says Coogle, it would be unlikely to affect the Saudi judiciary, who are responsible for issuing death sentences.

“The entire judiciary is essentially an arm of the religious establishment, and the potential for influencing them through negative media attention is very small - they live in a different world.

“Changing things would require a major rethink in society.”

Meanwhile, many within Saudi Arabia and outside it continue to complain that the justice system reserves the harshest punishments for the most vulnerable in society. In their final message, the seven men put to death for armed robbery pleaded for a complete overhaul of the Saudi justice system.

"Enact justice for those who steal billions, who corrupt the nation,” they wrote, “not for the victims of unemployment and poverty."

Middle East Eye propose une couverture et une analyse indépendantes et incomparables du Moyen-Orient, de l’Afrique du Nord et d’autres régions du monde. Pour en savoir plus sur la reprise de ce contenu et les frais qui s’appliquent, veuillez remplir ce formulaire [en anglais]. Pour en savoir plus sur MEE, cliquez ici [en anglais].