ANALYSIS: The slow death of al-Qaeda in Algeria

ALGIERS - It was an admission from the very top: his men were on the run or dead, popular support was almost zero, and allies across North Africa had fallen silent. Algeria was a dead zone for al-Qaeda, admitted its chief in northern Africa.

In his April 2017 interview for Inspire, the propaganda sheet of al-Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula, Abdelmalek Droukdel, the "emir" of al-Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb, or AQIM, painted a sorry picture.

We are bogged down in a long war... This has had a terrible impact

- Abdelmalek Droukdel, 'emir' of AQIM

"Support for the cause is generally good, with the exception of the Algerian front," he said.

"We are bogged down in a long war. The Algerian front suffers from scarcity, and sometimes an almost complete lack of support - inside and out.

"This has had a terrible impact."

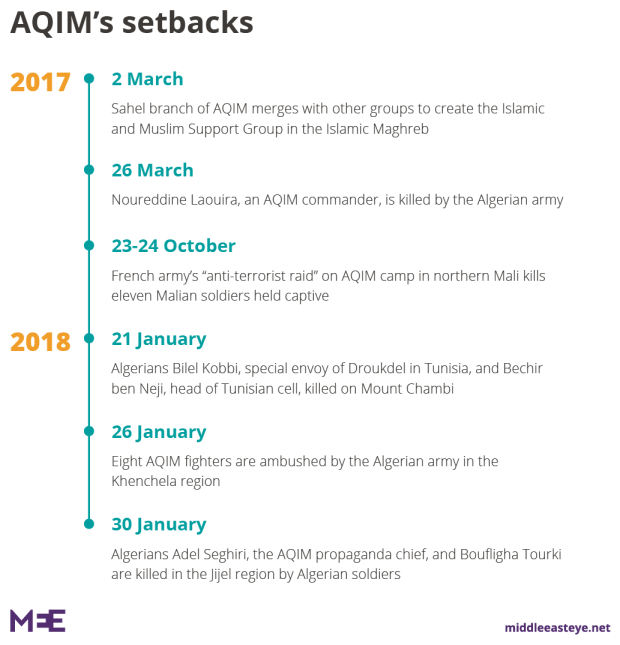

Little did he realise things would get worse. The rank-and-file was being thinned by repeated attacks by the Algerian army, but more costly was the loss of many of its executive branch.

Dead and buried

Bilel Kobi, the special envoy of Droukdel in Tunisia, and Bashir Ben Neji, emir of a group in Tunisia, were shot dead by the Tunisian military in January, In Algeria this week, Abu Rouaha al-Qassantini - real name Adel Seghiri - was killed by the Algerian army in Jijel, about 400km from Algiers.

He was the propaganda chief of AQIM, creator of the al-Andalus magazine and mastermind of the propaganda forum "Ifriquya al-Islamiyah" (Islamic Africa), which acted as message board between groups in the region and al-Qaeda in the Middle East.

Documents, a telephone and computer equipment found after his death proved invaluable material for the security services. Much of his network was compromised.

"He was among the 15 most dangerous AQIM fighters," an Algerian security source told Middle East Eye. "Not for his actions in the field but because he was in charge of encrypting and decrypting the information."

Born in 1971 in Constantine, Qassantini gained an electronic engineering degree in 1994 before joining the Armed Islamic Group (GIA) and later the notorious Salafist Group for Preaching and Combat (GSPC) in 2002.

"It is thought that he has probably continued to train in encryption practices through the internet," said one of the Algerian investigators who handled his case.

"Undoubtedly, it's a blow for the organisation and it will be weakened."

Algeria on the up

By law, Algerian military officials - both active and retired - are forbidden to speak to the media and Middle East Eye is unable to quote them by name. But all those who spoke have said the fight against al-Qaeda and its allies, after several years of setbacks, has swung decisively in the favour of the Algerian state.

AQIM has failed to carry out major attacks in Algeria for several months. The Algerian army says it eliminates an average of 200 militants each year and armed groups are finding it increasingly difficult to maintain their numbers.

So much so that last October, according to an Algerian security source, militant leaders pleaded for reinforcements from its allies in Tunisia and Libya.

How can the change in fortunes be explained? According to a retired Algerian major general, the state is "reaping the benefits of an anti-terrorism policy it has been pursuing for more than 20 years".

"This terrorism, we have always understood as both a security problem but also psychological, economic and cultural," he said.

Military operations, he said, were being run in tandem with efforts to marginalise armed groups' influence on the population.

As a result, "an almost complete absence of support inside", to use Droukdel's expression, is now manifest.

This was evident in 2015, when Madani Merzag, the former "emir" of a group known as the Islamic Salvation Army, a group notorious in the 1990s for a series of massacres, tried to form a political party. His attempt was roundly rejected by Algerians.

"There is no a secret recipe," said the retired general. "Eliminating a terrorist is not a victory if, at the same time, a recruit rises to take their place."

"We fail if [armed groups] are allowed to mobilise the youth. Draining terrorist financing can be an endless thing if you do not target their support networks.

Hit the logistics

A counter-terrorism source said: "The other mainstay of the security services has been to hit terrorist logistics.

"Some 1,000 members of support networks have been arrested in the last three years. For them, it is a real disaster that has forced dozens of terrorists and their families to surrender to the authorities. "

The tactics have not been received positively by all. NGOs are critical of Algeria's military tactics, and say regular announcements about the "elimination of terrorists" are opaque, and show there is no effort made to bring militants to justice.

But there is international support. In October, the deputy coordinator of the US State Department's counter-terrorism office called on Algeria "to share this experience with other countries around the world".

The tactics have had significant impacts as, according to an army analyst, militants have decided that "rather than fighting a far superior enemy, they would be better off moving elsewhere - Tunisia and especially Libya".

In recent months armed groups traditionally based in the Kabylie and Jijel mountains, coastal regions in the centre and east of the country have moved to the southeast near the Tunisian border.

The Chambi range in Tunisia is home to Uqbah ibn Nafi, the Tunisian branch of AQIM named after a seventh-century general of the Rashidun Caliphate.

But on both sides of the border, the vice has tightened and cooperation between security services, especially in Tunisia, has yielded results.

A week after the death of Bilel Kobi and Bashir bin Niju, a group of eight men was ambushed in Chechar, Khenchela wilayat, about 100km from the border.

Down but not out

But AQIM is not dead yet. In the south, in the Sahel, the situation is much different.

Thanks to strong alliances and money made from the ransom business, the organisation is able to sustain itself even in the face of pressure from an international force, known as Operation Barkhane, led by French soldiers.

Faced with the vastness of the desert and difficult weather conditions, the contingent that makes up the Barkhane force barely contain the attacks of AQIM under the unified banner of the Support Group for Islam and Muslims in the Islamic Maghreb.

As long as AQIM has fighters, it remains a threat

- Algerian security source

An Algerian security source solicited by MEE admits: "From an operational point of view, AQIM is in bad shape. I cannot over-emphasise how the elimination of Abu Rouaha al-Qassantini has hurt them."

He added that the Algerian army would soon flush out Droukdel, who is presumed to be hiding in the mountains of the Jijel region.

"But as long as AQIM has fighters, it remains a threat. We must never forget the story of Abdelhakim Belhadj's Islamic Fighting Group.

"It was said to have been completely destroyed but from 2011 was to reconstitute itself and fan out to several cities of the country."

Middle East Eye propose une couverture et une analyse indépendantes et incomparables du Moyen-Orient, de l’Afrique du Nord et d’autres régions du monde. Pour en savoir plus sur la reprise de ce contenu et les frais qui s’appliquent, veuillez remplir ce formulaire [en anglais]. Pour en savoir plus sur MEE, cliquez ici [en anglais].