ANALYSIS: From master to observer - how Turkey became irrelevant in Manbij

KOBANE, Syria – The Islamic State (IS) group is well known for its harsh crackdown on local populations and opponents, but the northern Syrian town of Manbij has been particularly hard hit.

Since IS stormed the strategically key town near the Turkish border in December 2014, there have been almost daily executions. The town’s Kurdish minority has born the brunt of the repression, but IS has also been brutal with the town’s Sunni Arab residents whom it suspects of supporting the Free Syrian Army.

When the tide began to turn against IS late last year, and anti-IS ground forces, backed by US-led anti-IS coalition planes, started making inroads against the militants in northern Syria, there were many cries from inside the city and the Syrian opposition that the town’s liberation should be prioritised.

Despite the town’s strategic value, and widespread belief that its recapture would greatly undermine IS’s ability to send foreign fighters and supplies into Syria, these calls for liberation were ignored until this week when a campaign was finally launched.

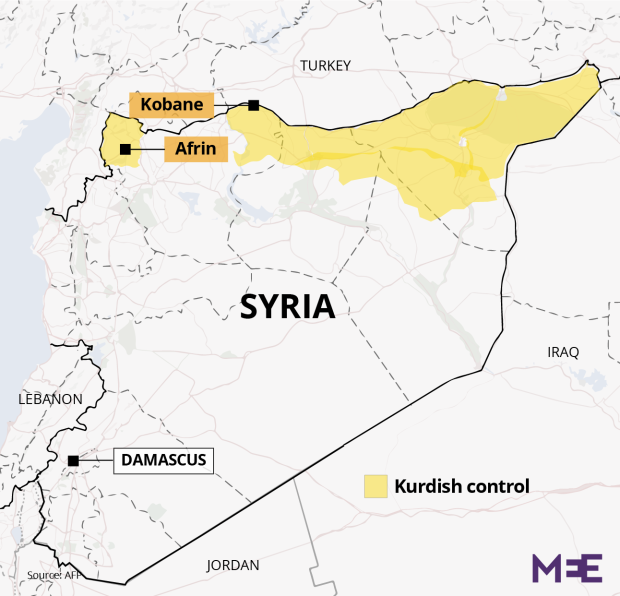

Turkey’s opposition to the offensive by the Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF), which it fears would connect the Kurdish towns of Kobane with Afrin, has been widely held responsible for the delay.

Ultimately, however, analysts say that there is not much that Ankara could do. Meanwhile, events in Syria have outpaced Turkey's fears of growing Kurdish influence at its border. As a result, Ankara’s worst nightmare – a Kurdish statelet on its border - seems to be a possibility.Last June, Turkey made clear to the Americans and the Kurds, that the Kurds crossing the Euphrates River into Jarabulus was a "red line" and only accepted the current US-backed operation on the condition that the Kurds would not advance further than between 3km and 6km from the dam on the Euphrates.

But the Kurds crossed this red line when they captured the Tisreen Dam on 26 December and now they are moving Turkey’s red lines even further.

“Turkey assisted the [Syrian] revolution with a good attitude in the beginning, but now it deals with us and the Kurds as enemies,” Sheikh Farouk al-Mashi, an Arab tribal leader who works with the Kurds in Manbij, told Middle East Eye.

Tug of war

Monday’s ground assault, which has already taken back some nine villages from IS, has been months in the making. Local civilian and military councils were set up at the beginning of April, but analysts say that the US wanted to hold off due to Turkish opposition.

But as IS suffered a string of setbacks in Iraq and Syria and momentum began to build, analysts say that Washington became convinced that it could delay no longer.

Nicholas Heras, a Washington-based Middle East researcher, told MEE that closing the Manbij pocket “would further bolster the US narrative that the current coalition strategy to defeat [the Islamic State group]” was working.

The control of Manbij is seen as a crucial piece of that strategy, with hopes high that its loss will curtail IS’s ability to bring in foreign fighters from Europe and Asia and reduce its ability to launch a counter-offensive.

Washington and Ankara have long had a tug of war over the Syria border. For years, the West has claimed that Turkey was purposefully lax in its monitoring in a bid to allow anti-government Sunni militants to bring in supplies, while also stressing that Turkey was a key ally in the anti-IS fight

Turkey on the other hand vehemently denied claims of aiding Sunni militants, and following a string of IS attacks on Turkish soil, it seemingly clamped down even further.

According to the US military, the number of foreign fighters joining the group through the Syrian and Iraqi border has dropped from 2,000 fighters per month, to 500 per month, but stemming the flow entirely has proved elusive.

Despite Turkey’s clear ability to impact the border, the extent of its involvement in the campaign to liberate Manbij is hotly contested.

Western analysts say the operation to take Manbij is most likely not coordinated with Turkey, although a US military official told Reuters that it was.

Aydin Selcen, a former Turkish consul, told MEE that Turkey is not supporting the operation, but doesn’t have many options to stop it.

“It can't do anything. It is beyond howitzer [artillery] reach and can't afford to disrupt US strategy directly,” Selcen said.

With Ankara not wanting to militarily intervene directly in Syria, the country has instead used used artillery shells to prevent Kurdish advances in northern Aleppo in March this year.

“I wouldn’t discount a potential outreach to Damascus against the SDF,” he added.

One-time allies Damascus and Ankara fell out sharply following the revolution to oust President Bashar al-Assad, with Turkey seen as a major backer of the non-Kurdish opposition.

However, Amberin Zaman, an analyst for the Woodrow Wilson Centre, told MEE that the operation was coordinated with Turkey to prevent Turkey attacking the Kurdish People’s Protection Forces (YPG). Turkey also wants to prevent the Kurds from completely controlling large parts of the Turkish border in northern Syria.

“Turkish fears over the YPG's well-known goal of linking Afrin with Kobane needed to be addressed,” Zaman told MEE.

“Thus the US flew in Arab members of the Manbij Military Council to Turkey to meet with Turkish officials to provide assurances that YPG would leave once the operation was completed,” she added.

“Obama pledged the same in his most recent phone conversation with [Turkish President Recep Tayyip] Erdogan.”

Some analysts have gone even further to suggest that Turkey, which has been embroiled in an internal conflict with the Kurdish Workers Party (PKK) at home and has opposed to its allies the YPG in Syria, will have to make peace with the Kurds if it wants to stay relevant in the anti-IS fight.

Zaman told MEE that Turkey now needs to make a deal with the YPG as Turkish-backed rebels have been losing ground in the north with the Islamic State making inroads in the Azaz corridor which rests some 75 kilometres west of Manbij and is a key lifeline to Turkish-backed opposition groups.

Time to cut a deal?

Concerns are now high that the latest counter-offensive launched last week by IS will see rebels lose their last Azaz stronghold of Marea.

“Turkey and the rebels will need to cut a deal with the YPG or risk losing everything,” she added.

Sharvan Darwish, a spokesperson for the Kurdish-led, US-supported Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF) told MEE that attempts by Turkish-backed rebels that tried to push back IS from Azaz in April were "a complete failure".

“In 15 minutes, all of [the Turkish-backed rebels] left, after they were attacked by IS, after just six members of IS attacked them in al-Rai,” he said, referring to the a border crossing that was recaptured by IS at the beginning of April.

Nor is this the first setback for the Turkish-backed opposition. Last year, a multi-million dollar initiative by the US to train and equip rebel forces in Turkey ended in failure when the group seemingly surrendered to al-Qaeda’s Syria affiliate the Nusra Front shortly after re-entering Syria.

The contrast with the SDF push launched earlier this year and heralded as a game changer has helped many in Kurdish majority areas to hope that military gains on the ground will eventually lead to greater political power.

SDF spokesperson Darwish told MEE that liberation of Syria from IS and not the unification of Kurdish areas was the main objective of the offensive but others say it is impossible to not look at what wider opportunities may lie ahead.

Ibrahim Kurdo, a foreign relations head of the local Kurdish self-administration in Kobane told MEE that he hopes the Manbij operation will help the Kurds set up a federal region.

“The people in Rojava [Syrian Kurdistan] and northern Syria look at the federal system as the future of Syria from Efrin, Azaz until [Hasakah province to the east],” he said. “They will be combined and united in a federal region, but it depends on the international situation, opportunities, date and time.”

Aaron Stein, a Resident Senior Fellow at the Atlantic Council, told MEE that Turkey increasingly realised it had few options left to prevent this.

“They have two bad options: use their own troops to close the pocket, or pull support from the [US-led anti-IS] coalition,” he added.

Middle East Eye propose une couverture et une analyse indépendantes et incomparables du Moyen-Orient, de l’Afrique du Nord et d’autres régions du monde. Pour en savoir plus sur la reprise de ce contenu et les frais qui s’appliquent, veuillez remplir ce formulaire [en anglais]. Pour en savoir plus sur MEE, cliquez ici [en anglais].