ANALYSIS: Turkey faces big legal battle to extradite Gulen

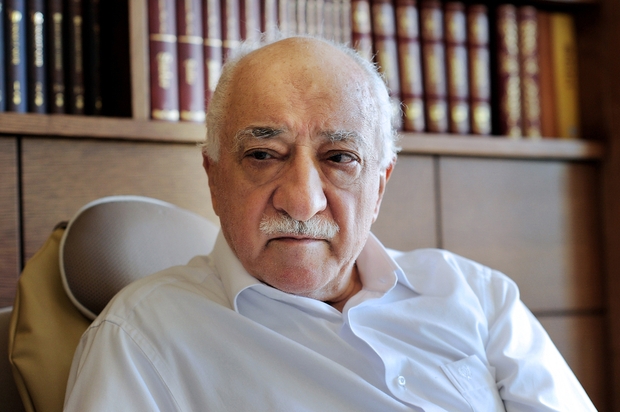

Turkish officials are expected to travel to the United States to push for the extradition of controversial cleric Fethullah Gulen, whom Ankara accuses of being behind the recent coup attempt in Turkey.

Turkey’s Justice Minister Bekir Bozdag and Interior Minister Efkan Ala are this week set to join Foreign Minister Mevlut Cavusoglu in a visit to Washington where they will demand Gulen’s extradition, Turkish newspaper Daily Sabah recently reported.

The diplomatic effort comes as Turkey has repeatedly called for the US to extradite Gulen, who has lived in self-imposed exile in Pennsylvania since 1999.

On Tuesday, Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan criticised the US government for requesting evidence of wrongdoing before it extradites Gulen to Turkey.

“What kind of partners are we if you request documents when we ask for a terrorist?" Erdogan reportedly said.

Gulen, meanwhile, has denied any involvement in the coup and accused Erdogan of going to “any length necessary to solidify his power and persecute his critics”.

“It is ridiculous, irresponsible and false to suggest I had anything to do with the horrific failed coup. I urge the US government to reject any effort to abuse the extradition process to carry out political vendettas,” Gulen said in a statement.

Turkey-US extradition agreement

But Turkey and the US are bound by an extradition treaty, and the two countries must satisfy a series of legal procedures and meet evidential standards before any official extradition request is granted.

The Treaty on Extradition and Mutual Assistance in Criminal Matters was signed between Turkey and the US in 1979 and lists 33 criminal offences that constitute grounds for extradition, including murder, kidnapping, rape, libel and arson.

To be grounds for extradition, the offences must be crimes in both countries - a standard known as “double criminality” - and be punishable by at least one year in prison. Extradition may also be granted if a person attempts to commit such an offence, or aids in the commission of an extraditable offence.

Geoff Gilbert, a professor of international human rights and humanitarian law at the University of Essex, said the US will have to answer two basic questions to meet the basic legal requirements for extradition: “Does it have the crime of attempting to overthrow the government, and does it have extraterritorial jurisdiction to prosecute?”

Gilbert told Middle East Eye he believes the US will be able to satisfy those questions on double criminality and extradition-worthy crime in Gulen’s case.

A clause in the 1979 treaty stipulates, however, that extradition will not be granted for an offence if it is of “a political character,” or where extradition seeks to prosecute or punish a person “on account of his political opinions”.

But Gilbert explained that the US takes a different approach to most other countries in determining whether a crime meets the political offence exception.

“No extradition court in Europe would hand anybody over to Turkey at the minute,” he said.

In Europe, an extradition order would be refused on the basis of the political offence exception if the crime is part of a “political disturbance”. In the US, meanwhile, the exception is generally only applied to crimes that are part of a larger “political uprising”.

“In this particular case, whilst the coup was basically very short lived, it’s arguable that a US court would find there was no political uprising, that it never actually reached that level,” Gilbert said.

“In the rest of the world … they don’t look for a political uprising. They look for a political disturbance, and a political disturbance is less than a political uprising.”

European countries would also not consider extradition right now given Turkey’s decision to suspend the European Convention on Human Rights, Gilbert said.

The sub-exception in the treaty also states that any offence committed or attempted against a head of state, or head of government, will not be deemed to be of a political character, although Gilbert said the Gulen extradition case would likely not qualify.

“This is not an offence against the head of state or head of government; this was an attempted coup,” he said.

Gilbert also noted that the treaty specifies that a person may only be charged with the crime that served as the basis for his or her extradition order.

The extradition process

The US “has relied almost exclusively” on bilateral agreements on extradition, and it holds such deals with over 100 countries, legislative attorney Michael John Garcia and US public law expert Charles Doyle explained in a 2010 paper on US extradition law.

The US received and submitted less than 50 extradition requests annually up until the early 1970s; about a decade later, that number had reached 500 per year, the researchers reported.

An official request for extradition is generally submitted to the US for consideration through diplomatic channels. The request then makes its way to the US Department of Justice and the US State Department.

The DoJ determines the legality of the request: whether the crime or crimes satisfy the standard of double criminality, whether the crime or crimes are political in nature, and if there is enough evidence to establish probable cause.

Probable cause is a US legal standard by which police can make an arrest, conduct a search, or receive a warrant from a court, and it is used during a preliminary hearing in criminal cases. A court can rule there is probable cause that a crime has been committed based on indirect evidence, including affidavits from people who are not necessarily witnesses to that crime.

The critical point in US extradition cases is that the evidence is “reviewed from the point of view of US legal standards, not Turkish standards,” a source familiar with Gulen’s case told Middle East Eye on condition of anonymity.

If the DoJ finds that the extradition request meets all the legal requirements, the case then goes before a federal magistrate court in the district where the person being requested for extradition resides.

That court will decide, “whether the request is in compliance with an applicable treaty, whether it provides sufficient evidence to satisfy probable cause to believe that the fugitive committed the identified treaty offense(s), and whether other treaty requirements have been met,” Garcia and Doyle wrote.

The source said the hearing in Gulen’s case would take place in the Middle District in Scranton, Pennsylvania. In extradition cases, a defence team cannot directly appeal the court’s order on extradition, but it can file a habeas corpus petition and appeal that up to the US Supreme Court, the source explained.

The US Secretary of State then makes the final decision on granting extradition and once more examines the legality of the request and whether it is political in nature. At this third and last stage, the defence can file a petition to block extradition on the basis of the UN Convention Against Torture, to which the US is a signatory.

“It’s really at the State Department level where the concerns about torture are most relevant,” the source said.

“The legitimacy of the evidence, the validity of the evidence, is certainly a consideration when the DoJ and the court look into this,” the source added.

‘Genuine evidence’ needed

A US State Department spokesman confirmed on 19 July that the US had received documents from Turkey, and that US officials were in the process of examining their contents.

Mark Toner did not specify what those documents covered or whether they constituted a formal request for Gulen to be extradited to Turkey.

“I don’t think I can stress enough that this is not an overnight process. That’s just not how these processes work,” Toner told reporters. “So this is going to take some time, but we’re going to stand by the extradition treaty and we’re going to act in accordance with the extradition treaty.”

According to Bruce Zagaris, an attorney at Berliner Corcoran & Rowe LLP with experience on US extradition cases, the process hinges on what crime Turkey is seeking to charge Gulen with.

Treason and conspiracy to overthrow a government are charges that would generally be treated as political offences and the US could refuse to extradite Gulen on that basis, Zagaris said.

But if Turkey can provide evidence that Gulen was directly involved in a conspiracy to commit murder, for example, that would be another matter.

“Unless Turkey can show evidence that he was directly involved in trying to commit some other offence, they’re going to have difficulty,” Zagaris told Middle East Eye. “And right now, nobody knows” what Turkey wants to charge Gulen with, he added.

US Secretary of State John Kerry, meanwhile, said the US would only approve an extradition request if Turkey can demonstrate “genuine evidence” of Gulen’s wrongdoing.

“We need to see genuine evidence that withstands the standard of scrutiny that exists in many countries' system of law with respect to the issue of extradition,” Kerry said. “If it meets that standard … there's no interest we have in standing in the way of appropriately honouring the treaty that we have with Turkey.”

Impact on US-Turkey relations

Cavusoglu, Turkey’s foreign minister, warned last week that Turkey-US ties would be negatively affected if the US does not extradite Gulen.

“Extradition does involve in part diplomatic relations and Turkey seems to be aggressively trying to push the international relations aspect of the case,” Zagaris said.

He compared it to the Iranian government applying pressure on the US to extradite the country’s former Shah, Mohammad Reza Pahlavi. Pahlavi sought medical attention in the US for a brief period after he fled Iran following the Islamic Revolution in 1979.

But Zagaris said despite the impact extradition cases can have on foreign relations, and vice-versa, “it’s very difficult to influence the US extradition process”.

“There are officials in the State Department and the Department of Justice who will review the application and if they see that the request is part of Turkey’s broad effort to crack down on political dissent and is politically motivated, they’re likely to refuse to process the request,” he said.

Zagaris said the process could take several years and Gulen’s health and advanced age (he is currently 75-years-old), as well as the political context in Turkey at the time of extradition may also play roles in the US’s decision.

Turkey has carried out widespread arrests and suspended public servants, judges, teachers and other professionals whom the government has alleged had a hand in the attempted coup. Human rights groups have also raised concerns about the mistreatment of detainees and Turkey’s consideration of bringing back of the death penalty.

Gulen’s defence team could use this context to argue against extradition in court, Zagaris explained.

“Another question that would come up would be whether Mr Gulen if extradited would be able to have a fair trial,” he said. “A court’s not supposed to look at that, but in this case, that could also be a potential problem for Turkey.”

This article is available in French on Middle East Eye French edition.

Middle East Eye propose une couverture et une analyse indépendantes et incomparables du Moyen-Orient, de l’Afrique du Nord et d’autres régions du monde. Pour en savoir plus sur la reprise de ce contenu et les frais qui s’appliquent, veuillez remplir ce formulaire [en anglais]. Pour en savoir plus sur MEE, cliquez ici [en anglais].