ANALYSIS: What are the implications of Russia-US cooperation for Syria?

Now that Vladimir Putin and Barack Obama have held their first formal meeting for two years, how does the Syrian war proceed?

Will the two men’s vague talk of co-ordination make any difference to the battle lines between the Syrian army and the forces of the Islamic State (IS) group?

Can the Syrian Kurds succeed in their plan, backed by the United States, to push IS from the last crossing point to Turkey, thereby blocking the flow of volunteers to IS?

For the moment these questions have to remain open. But what is clear is that Putin has had a productive week. If good timing is the hallmark of a great tactician, then his decision to seize the initiative on Syria was a masterstroke.

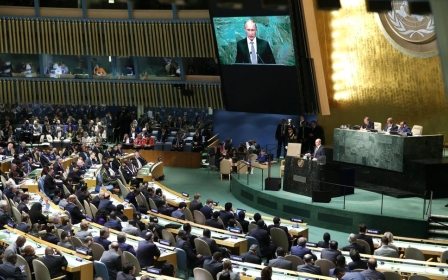

At least four factors had prepared the ground for Syria to become the dominant theme at the UN general assembly and give Putin the chance to stand out above the crowd of leaders, Obama included.

Firstly, the drama of small numbers of Muslims from almost every European country going off to join IS has dominated tabloid newspapers over the past few months, heightening fears of blowback when they return.

Secondly, in a way that nothing else has done over the last four years the sudden surge of Syrian refugees risking their lives to reach Europe alerted European politicians to the need to go to the source of the country’s despair and help to end the civil war.

Then came the revelations that the US programme to train a secular rebel force to confront Bashar al Assad’s army had failed to produce more than a handful of fighters.

Finally there was increasing recognition among Western think tanks and many Western governments of two things: no political solution could be brokered for Syria if Assad’s resignation was insisted on as a precondition; and some way had to be found to preserve the institutions of the Syrian state and its army, whatever happened to Assad, if chaos were not to ensue as in post-dictatorship Iraq and Libya.

While none of these issues were new, they combined this summer to reach a critical mass. People sensed that Washington and its anti-IS coalition were floundering and there had to be new thinking.

Enter Putin.

The Russian president had hinted several months ago that he would attend this year’s UN General Assembly. His motive was to counter the Western focus on Russia’s military involvement in Ukraine and show he would not be cowed by sanctions and other efforts to isolate him.

But he decided that the best way to do that at an international gathering was not to concentrate on explaining his thinking on Ukraine, which would look defensive.

A more dynamic approach was to change the UN meeting’s agenda, offer unexpected solutions, and make headline-grabbing moves that may start to bring them about. The crisis in Ukraine, for all the noise that NATO makes about it, has produced a death toll of civilians in a year and a half that roughly equals the number killed in Syria in an average month.

Syria is clearly the bigger crisis, and in order to focus attention on it, and on Russia’s ability to influence it, Putin turned to a favourite instrument - hard power.

By sending Russian tanks, aircraft and advanced weaponry to Syria and increasing the number of Russian advisers there he got everyone talking. This was not a covert intervention as in the Ukraine but a deliberate flaunting of hardware and troops that Putin wanted the world to see.

He was careful to say Russia would not be committing its ground forces into battle but he was less clear on whether Russian aircraft would be involved. Russia would certainly be arming the Syrian air and ground forces with better tools.

Although the media made much of Putin’s allegedly unconditional support for Bashar al Assad, the Russian leader’s comments were carefully phrased to suggest he wanted serious change. Particularly in an interview with CBS before leaving for New York, he talked of the need for reform and transformation in Syria.

“There is no other solution to the Syrian crisis than strengthening the effective government structures and rendering them help in fighting terrorism, but at the same time urging them to engage in positive dialogue with the rational opposition and conduct reform,” he said.

As for Russian aid to the Syrian government and army, “we do it hoping that Syria will launch the political transformation necessary for the Syrian people”.

So how will the war go now?

A year since it began, the US bombing campaign has not blunted IS’s fighting capacity. IS was blocked from advancing last autumn from Mosul to Erbil, the capital of the Kurdistan Regional Government of Iraq, but it compensated by seizing Ramadi in Iraq and Palmyra in Syria this year.

Kurdish success in northern Syria

The most successful anti-IS front has been in the Kurdish regions of northern Syria where the so-called People’s Protection Units (YPG) drove IS out of Kobane after four months of fighting, the longest battle of the IS war, and then out of Tal Abyad.

The two towns were important crossing points for IS volunteers, and finance to pay for their fighters, as well as transporting weapons. In both cases US bombing played a major role.

In Kobane IS resisted fiercely. The town had become a symbol, and IS sent hundreds of men into battle.

Tal Abyad, by contrast, was relinquished with little fight, once IS realised their communication lines were about to be cut south of the town, leaving their forces surrounded.

As Misro Munzir, a 21-year-old soldier who was recovering from a leg wound in Kobane’s military hospital after fighting in Tal Abyad, told MEE last week: “Da’esh [the Arabic acronym for IS] didn’t fight hard in Tal Abyad. The experienced fighters withdrew and only twenty five others stayed behind. They were confused by the airstrikes”.

One of the next fronts looks set to be the sector of the Syrian-Turkish border, west of the Euphrates, that connects Jarabulus with Azaz. According to Fuad Hussein, Kurdish President Massoud Barzani’s chief of staff, the YPG has won US backing for a coordinated campaign of ground forces, aided by air strikes, to liberate the region.

“I know the US are focusing on Jarabulus to cut the movement of terrorists”, he told MEE in Erbil. “The US are planning to cut all the roads which lead to the main cities under IS control. Fighting them inside the cities is hard. It’s easier to isolate cities, and isolation can start with cutting the roads."

Asked if US support for seizing the last IS-controlled crossing from Turkey by military force showed the US lacked confidence that Turkey would close the border to IS militants by itself, Hussein said: “I’m not saying that. Co-operation between Turkey and the Americans is good."

He implied that Turkey had given Washington assurances that it will not bomb YPG forces when they assault the Jarabulus-to-Azaz area.

If the Jarabulus front is one impending battle, another may be around Palmyra. Syrian state media claimed last week to have captured two villages west of Palmyra which had earlier fallen to IS.

Coordination with Syrian army?

It would be logical for the Syrian army to continue their forward thrust. Syrian planes have already been bombing the town Palmyra itself several times in recent weeks.

A key test of the promised US-Russian co-ordination would then be if the Russians alerted the Pentagon to a planned advance by the Syrian army so that Syrian and US aircraft could plot their bombing targets together.

Syrian planes and US planes were in the skies simultaneously over different parts of Hasaka, a town in northern Syria which is divided into a government-held area and a larger YPG-held area, after it came under IS attack in July, according to witnesses who spoke to MEE last week.

The geography of the town meant that co-ordination between the two airforces was not required in the way that it would be needed in an effort to liberate Palmyra.

The US bombing campaign has forced IS to change tactics. Instead of hundreds of troops advancing in vehicles it is increasingly resorting to tactics from the Iraq war a decade ago - suicide bombings by car-drivers and individuals on foot.

The Kurdish region of northern Syria has seen numerous explosions in recent weeks, three in one week in Hasaka alone. In Kobane in June IS infiltrated dozens of fighters wearing YPG uniforms who massacred over 200 civilians in a combination of revenge for their earlier defeat and as a sign that they are still a force.

In Iraq IS has lost ground in recent months west of Kirkuk. But Fuad Hussein, the Kurdish president’s chief of staff, is under no illusion about the danger IS still represents. He has regular discussions with US diplomats and generals.

“Daesh being in Mosul is a threat to us. They can easily reorganise and move from one place to another. If they can get more weapons and manpower they will move out of Mosul. They’ve become weaker. They’re losing ground and much equipment but they can still move within 50 per cent of Syria,” he said.

Whether US-Russian co-ordination can reduce IS’s strength remains to be seen.

Middle East Eye propose une couverture et une analyse indépendantes et incomparables du Moyen-Orient, de l’Afrique du Nord et d’autres régions du monde. Pour en savoir plus sur la reprise de ce contenu et les frais qui s’appliquent, veuillez remplir ce formulaire [en anglais]. Pour en savoir plus sur MEE, cliquez ici [en anglais].