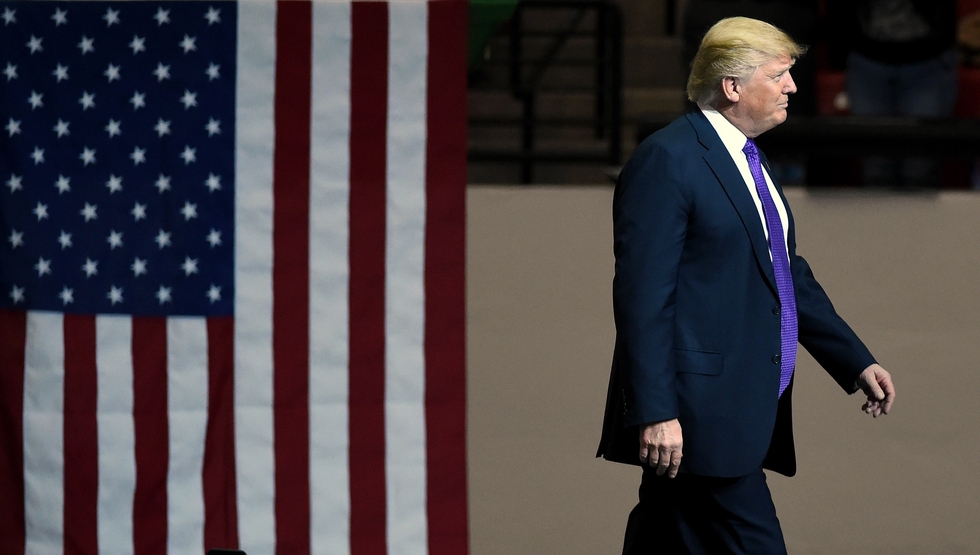

ANALYSIS: White American anxieties paving Trump’s road to victory

WASHINGTON - As Super Tuesday ended and Wednesday rolled in, many Americans woke up to the realisation that Donald Trump, the celebrity and eccentric billionaire, could very likely win the Republican nomination for president of the United States.

Trump swept to victory in seven of the 11 contested Republican states, triumphing over rivals everywhere but Texas and Oklahoma - which Senator Ted Cruz managed to win, and Minnesota, the only state won so far by Florida Senator Marco Rubio.

Trump's ascent has been surrounded with controversy, as he has blamed America's woes on China, Mexican and Syrian immigrants, and even African-Americans. Despite this discourse, 49 percent of Republicans said they support him, a recent CNN poll found.

“There’s a growing segment of the American population - who are mainly white - who feel like a silent majority that's being discriminated against,” said Rabiah Ahmed, media and communications director at the Muslim Public Affairs Council (MPAC). “They see minorities as taking over the country under the watchful eye of an African-American president.”

“They feel that what they see is the authentic identity of America changing with the changing demographics of the nation,” she told Middle East Eye. “And here comes along Trump who makes these statements and touches up on the fears they have and does so in a way that it’s acceptable. He's normalising these prejudices.”

Trump has steamrolled ahead despite his disparaging comments against immigrants, women and people with disabilities, but his anti-Muslim rhetoric has attracted condemnation from both sides of the political aisle, leaving some in the Republican establishment scrambling to thwart his efforts for the nomination.

But to his supporters, his anti-Muslim proposals have been a defining point of his campaign. It started in November 2015, following the Paris attacks that claimed the lives of 130 people, when Trump said he would support close surveillance of mosques, and suggested introducing a nationwide database to register Muslims.

His tropes have included a discredited claim that he saw footage showing “thousands of people” in Jersey City where “you have a large Arab population” celebrating the 11 September attacks in 2001. At a rally in Virginia on 19 February, he told a crowd a fictional story of a general who killed Muslims with bullets dipped in pigs' blood. A few days earlier, he singled out Syrian refugees, vowing to bar them from the country. This came on the heels of his ardent defence of waterboarding, along with other methods that are “much worse,” because, as he put it, “torture works”.

Muslim ban

The most divisive proposal of his campaign, however, has been banning Muslims from entering the US. His remarks, unprecedented for a leading presidential candidate, were met with swift repudiation even by his own party, and prompted Paul Ryan - the Republican Speaker of the House - to speak out on two different occasions in recent weeks.

“If a person wants to be the nominee of the party, there can be no evasion and no games,” Ryan said on Tuesday. “This party does not prey on people's prejudices. We believe all people are created equal in the eyes of God and our government. I hope this is the last time I have to speak out on this race,” he added.

Some say they believe Trump's manoeuvring against Muslims appeals to a certain strata of society: some conservative white voters feel resentful of Barack Obama’s presidency, and, while angry and anxious about safety at home, they look for an easy solution to a complex security problem.

Despite the condemnations and negative publicity, Trump's star continues to shine - his poll numbers are rising and the crowds attending his events are growing. His pointed suspicions about Muslims have only bolstered up his base of support, especially among Americans who feel restrained by what they call political correctness.

“People now feel it is more acceptable to say hateful things out loud,” said Jim Walsh, research associate at MIT's Security Studies Program. “Some candidates have made it okay and created a safe haven for them to say things they didn't before – for fear of being shamed. They are now seeing this rhetoric as a way to combat political correctness.”

Walsh added that being more open about racial animus has become more permissive given the prevailing anger about economic stresses and racism against Barack Obama throughout his presidency. “It's all been stewing together in the same pot for some time,” he said.

Early on in his candidacy, Trump targeted Mexican immigrants with his inflammatory tenor, going as far as to call some rapists and vowing to build a wall along the southern border to keep them out of the US. His rhetoric took on a sharper tone when Syrian immigrants started to flee to Europe, and Washington was under pressure to increase the number of refugees that it would accept, much to the ire of Republican candidates.

Then came the Paris attacks and the mass shooting in San Bernardino, California, which was carried out by a Muslim couple. These paved the way for Trump's most audacious proposal: “A total and complete shutdown of Muslims entering the United States until our country’s representatives can figure out what the hell is going on.”

The Evangelical vote

While some were aghast that a mainstream presidential hopeful would make such a suggestion, polls showed that nearly 60 percent of respondents supported his proposal. As concerns over terrorism continued to rise in recent months, some said Trump's attempt to soothe growing anxieties about security resonated with many - which is why he seems to be doing so well with Evangelicals.

“Many candidates are not focused on what have traditionally been Evangelical issues - like abortion - as they were in the past,” said Scottie Nell Hughes, chief political correspondent for USA Radio Networks, which produces and distributes radio programs with a generally conservative and Christian focus.

“Evangelicals just like everyone else are focused on the economy, but also on security, which is why Trump is having such a great time,” Hughes told MEE.

Without naming Trump, President Obama said anti-Muslim rhetoric could serve as a recruiting tool for militants like the Islamic State (IS) group. And, some argued, that it would alienate the very same community that most often acts as a bulwark against these groups.

“The problem with demonising a societal group is ethical and moral, but from a security standpoint the problem is that it makes relations with that group more difficult,” Walsh told MEE.

“When you have people who might commit acts of terror, you want the support and trust of the Muslim community to do good police work. If you are insulting the community, that will undermine law enforcement.”

The Southern Poverty Law Center, which tracks hate groups, has warned that Trump's comments are conducive to anti-Muslim violence. Trump has gained support from white nationalist, neo-Nazi organizations like the Daily Stormer, and anti-Muslim advocacy groups, like the Society of Americans for National Existence. He has also won the backing of David Duke, a former Ku Klux Klan grand wizard.

Citing normalisation of hate as a concern, the centre said that the number of extremist groups in the US has grown dramatically over the past year, pointing to hateful rhetoric from presidential hopefuls, growing frustration over police killings and terrorist attacks as culprits. The centre also said that Trump contributed to “a political war along racial and ethnic lines” through his “demonising statements about ... Muslims,” which have “electrified the radical right”.

The Muslim-American community has been working hard to combat the fallout created by Trump's inflammatory comments, which, it said has made the racial divide in the US all the more pronounced.

“We need more Americans to push back and take a stand against it,” MPAC's Ahmed said. “Those who do want to oppose Trump have to register to vote and get into campaigns and get involved, because after all, it's a numbers game. We are not going to change people's perceptions and attitudes unless we are engaged. When we have people trying to demonise us, we have to shape our own story.”

Middle East Eye propose une couverture et une analyse indépendantes et incomparables du Moyen-Orient, de l’Afrique du Nord et d’autres régions du monde. Pour en savoir plus sur la reprise de ce contenu et les frais qui s’appliquent, veuillez remplir ce formulaire [en anglais]. Pour en savoir plus sur MEE, cliquez ici [en anglais].