Abuse in Saudi Arabia: How Bangladeshi maids escape ‘dream job’

The crowds wait outside the arrivals terminal at Shahjalal International airport as dozens of taxi drivers line the streets looking for business.

Armies of beggars plead for attention from passersby, while passengers leave the arrivals hall carrying flat-screen TVs or oversized boxes wrapped in cling-film.

A group of women appear amid the constant stream of people. Dressed in an array of colours, they pull their suitcases, looking for their loved ones.

Khaleda Akhter, 28, has just spent months inside a Bangladeshi-run safe house in Saudi Arabia, and is desperate to see her two children. Holding a copy of the Quran to her chest, she scans the arrivals hall for the exit, then begins to walk towards the double doors. Initially, her steps are slow and steady, as she takes in what has changed since she left Bangladesh a year ago.

Akhter figures out where to head, clutches her black abaya to avoid it dragging on the ground and begins zipping through the traffic to the train station. From there, she will embark on the next leg of her journey back home to Rajshahi, 250 km away near the border with India.

But underneath her clothing lies a reminder of why Akhter left Saudi Arabia. Unravelling the bandages on her arms, she shows the marks that symbolise the price she paid for wanting a better life.

"They tried to burn me,” Akhter says, wiping away a tear. "Not once, but twice. If I knew this would happen, I would never have gone.”

'I had to give it a shot'

Like hundreds of Bengalis who went to work as domestic workers in the Gulf kingdom, Akhter fled her employers after months of abuse.

She represents one of the thousands of women from the country who each year make the journey to the kingdom in the hope of a better life.

In 2018, at least 1,000 Bengali maids returned to Bangladesh to escape physical and sexual abuse in Saudi, according to local NGO BRAC. Most escaped to one of the safe houses run by the Bangladeshi embassy in Riyadh and Jeddah.

Many have been not been paid by their employers and had their passports taken away by recruitment agents, who first sold them the dream of working in the Gulf state.

Akhter sits in the restaurant adjacent to the train station, holding the hand of Aisha Begum, a fellow domestic worker, who ran away from an employer who did not pay her for four months and repeatedly beat her.

The restaurant is packed. Plates of rice and curry are ferried between the kitchen and tables. Waiters hand out cups of chai.

When Begum, 45, speaks to Akhter, she does so with confidence, looking her companion in the eye: the women are looking forward to their first shinghara, a fried potato snack popular on the Indian subcontinent. Begum pulls back her green hijab, her gold earrings visible beneath her headscarf and tries hard to attract the attention of the waiters.

“I’ve waited nearly a year for this,” she says, as she eventually sips her first cup of chai since arriving home.

Akhter and Begum met in the safe house in Jeddah in late 2017, where Akhter stayed for three months and Begum for two.

Begum recalls how her ordeal at the hands of an abusive employer lasted for three months, never knowing when she would next be hit. “My god, that tension was too much," she says and begins to cry.

"I only went to Saudi Arabia to make a better life for myself and family. What work is there in Bangladesh? Everyone is leaving at the first opportunity they get. I had to give it a shot."

The brokers who sell the dream

Begum and Akhter left Bangladesh with the help of one of the thousands of brokers - known as a dalaal - who are based across Bangladesh, from the largest cities to the smallest villages, arranging passports and visas and guaranteeing employment in Saudi homes. The brokers in turn work for the recruitment agencies who are mostly based in Dhaka.

The majority of the maids working in Saudi come from villages like Akhter’s, where poverty is rife and it’s easy for brokers to sell them dreams: the promise of earning hundreds of dollars, the chance to visit Mecca and Medina, and a safe workplace where they will not face abuse.

It’s easy for brokers to sell dreams in poor villages: the promise of earning hundreds of dollars, the chance to visit Mecca and Medina, a safe workplace

Despite not having enough money, many women take the risk and pay up, perceiving the extortionate recruitment fees as an investment. Some even sell land or take out loans from family to raise the money to leave.

"The image of going overseas represents not only wealth but a status-symbol within Bengali culture," says Ali Ahmed from the Human Development Research Centre, a migrant rights NGO based in Dhaka. "Brokers go into rural communities where they directly recruit the women on behalf of the agencies.

"The key expense should be the passport, but they [the brokers] add a premium to their services to get a visa and other documents."

For each woman they recruit, the brokers charge between 30,000 to 60,000 takas ($360-$720): of that, the cut for the brokers comes to $120. Bangladesh is one of the poorest nations in the world, with a GDP per capita in 2017 of $1538: in outlying rural areas, it is a lot less.

When migrants began leaving Bangladesh during the 1970s, there were two ways: directly through the Bangladeshi ministry of manpower; or through recruitment agents. Most Bengalis use the latter to avoid the corruption endemic in Bangladesh bureaucracy.

In 2017, Transparency International's Corruption Perception Index ranked Bangladesh as 143rd out of 180 with a score of 28/100.

Ahmed believes that many Bangladeshis trust brokers for work overseas because they are "known to the families" and "easy to reach if there is any trouble”.

But even going through the brokers, the network of corruption further compounds and inflates the final cost for the workers, who have no one to represent their interests.

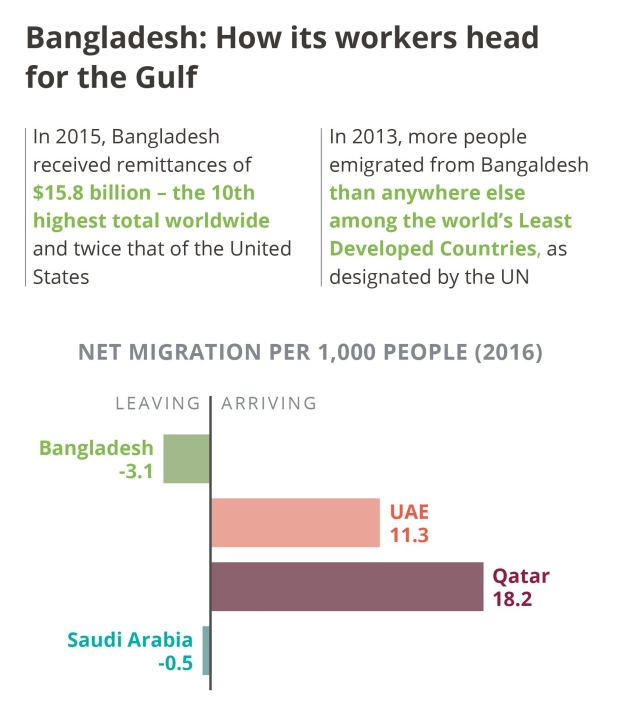

The brokers are unregulated, despite their widespread use. Migration is also good for Bangladeshi government finances: remittances from foreign workers are the second highest source of income for its economy.

Both Akhter and Begum approached brokers in their villages. "The dalaal said the place is perfect, the wages are excellent, they won't hit you or anything," says Akhter.

But the reality was very different.

'I remember the trickle of petrol going down my back'

Life in Saudi was good for Akhter, to begin with. She worked long hours but had a stable and safe job, cooking, cleaning and looking after her sponsor’s children. She was paid on time, allowed to call her family back home and given the freedom to leave the house when she pleased.

But the abuse began when her Saudi sponsor, a policeman, died five months after she arrived.

"The Saudi man who sponsored my visa was good to me and treated me properly," she says. "But after he died, his wife started to hit me. And when the wife finished with me, her other family members would later join in."

She ran out of the house in the middle of the night. 'My heart was beating,' she says. 'I knew if they caught me, I’d face hell from them'

For Akhter, the abuse went from being punched and slapped to attempts by her employer to burn her alive.

"I remember the trickle of petrol going down my back," she says. "I thought I was dreaming. Then I started to feel the heat. That's when I started screaming and panicking. It just made no sense. Why would they do this to me? I had to run away."

Akhter had been banned from using her mobile after the death of her sponsor, so had to call her broker in secret. He ignored her calls and only responded, telling her to flee, when she called her mother.

She was also given the number for BRAC, one of the biggest NGOs in the world, which is based in Bangladesh and has helped citizens facing abuse overseas.

Akhter waited till the family was asleep, gathered her few possessions and ran out of the house in the middle of the night. “My heart was beating," she says. "I knew if they caught me, I’d face hell from them."

She walked for miles in the desert heat before being stopped by a Saudi police patrol. “They asked me where I was going and what I was doing on the street. I tried to explain to them that I had had enough, but when they heard 'Bangladesh' and 'safe-house', they knew exactly where to take me.”

At the safe house, Akhter contacted BRAC case worker Noyon al-Amin and they began messaging via IMO, an app used by millions of Bengalis to help arrange their travel home.

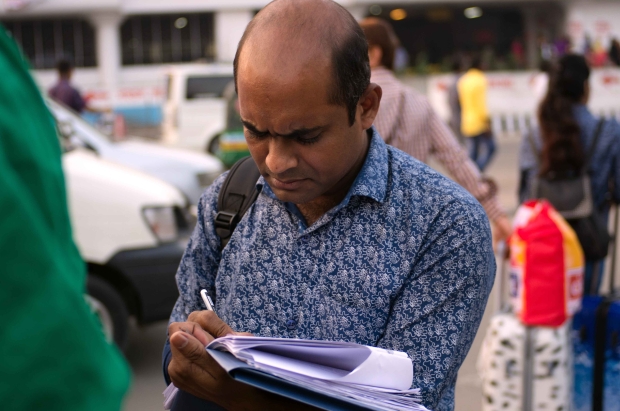

Amin joins Akhter and Begum in the restaurant, although not for long: he is constantly running in and out between cups of chai as he juggles transport arrangements for the two women and messaging other abused workers who are due to return.

Short and with a stubbly beard, Amin is a common sight outside the airport, holding a clipboard and waiting for new arrivals. He visits the terminals daily to meet abused workers and help them get home. Sometimes he has to identify the bodies of migrants which are brought back in coffins from Saudi and elsewhere several times a week.

Taking a towel out of his pocket to wipe the sweat off his forehead, Amin opens up WhatsApp and IMO and begins to go through the dozens of messages he receives daily from maids and workers inside Saudi Arabia, asking for help.

We had a case not too long ago where three women who came back from Saudi Arabia had turned clinically insane

- Noyon al-Amin, case worker

"Look, you can see that this woman was burned with a cigarette,” he points. “And this woman was hit with an iron. Nearly all the cases we have tracked in the last six months have come from Saudi Arabia. After they contact us, we then flag up their case to the Bangladeshi embassy in Riyadh. From there they head to the safe houses."

Amin knows first-hand the psychological trauma that these women face: he himself was trafficked to Malaysia with the promise of work in an electronics factory, only to be taken to the jungle and forced to cut down trees alongside dozens of Bengali and Tamil workers. “Many of the men we worked with died after being bitten by snakes and other insects when cutting down the trees,” he says.

Eventually, he escaped and now advocates for Bengalis working overseas.

Traumatised in the safe house

The Bangladeshi government set up the safe-houses in the early 2000s, according to local media reports, to meet demand. MEE has obtained diplomatic cables sent from the Bangladeshi embassy in Saudi Arabia back to Dhaka, requesting more resources from the ministry of foreign affairs (MOFA).

The cables, which date back to 2015, report that at least three to four women are coming to the embassy daily, asking to be repatriated.

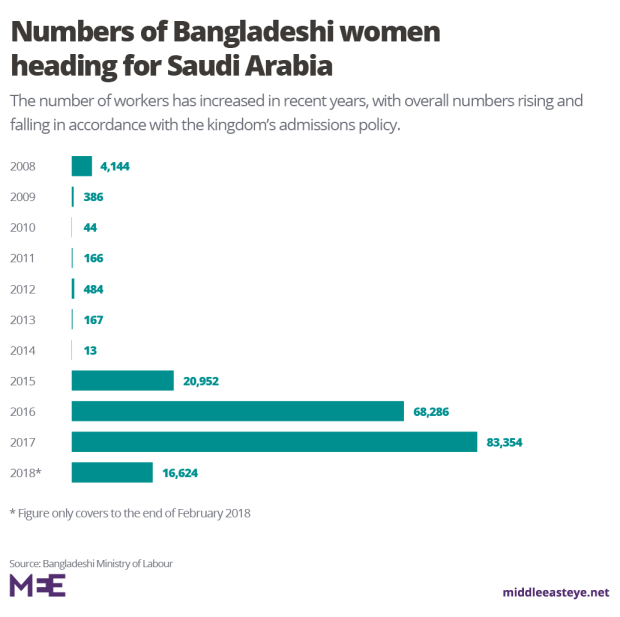

That number is likely higher now. According to official figures released by the Bangladeshi Ministry of Labour, 20,952 women were permitted to work in Saudi Arabia in 2015. That number quadrupled to 83,365 in 2017, when Saudi authorities relaxed restrictions to respond to a need for more domestic labour.

But while Bangladesh encouraged more women to work in Saudi Arabia, other countries have introduced measures to stop women heading for the kingdom and other parts of the Gulf following reports of abuse.

In early 2018, the Philippines introduced a ban on women working in Kuwait, after reports of Filipina maids being physically and sexually abused.

Likewise, in 2014 Indonesia imposed a ban on female domestic workers in 21 Middle Eastern countries, including Saudi Arabia.

Bengali diplomats in Saudi, by contrast, requested more resources in anticipation of an increase in abuse cases. Bangladesh's Ministry for Foreign Affairs and the embassy in Riyadh did not reply to requests from MEE for comment or the current numbers of women inside the safehouses.

But MEE spoke to a dozen other former maids who lived in the shelters and put the number of those inside in the hundreds.

"There are loads of women inside the safe houses, but I am grateful for the way they looked after me," says Begum. "It was a moment of peace after facing so much in Saudi. But many women want to leave."

'There was so much blood'

Images and videos obtained by MEE from inside the safehouses show women being allowed to walk around freely.

Nine women were trying to hold down nine wounds. She cut herself on her hands, feet, and torso. The blood was glistening on the floor. If we never did that then she would have bled out completely

- Khaleda Akhter describes a suicide attempt in a Riyadh safe house

But the wait has also traumatised some, who have been abused yet are stuck in Saudi either because they lack the relevant papers or their employers have accused them of crimes which the women say they did not commit.

Sometimes the frustration boils over.

One video sent from a Saudi safehouse to Amin showed a Bengali maid having a panic attack screaming "take me home, take me home." The footage showed other inmates of the shelter holding down the distressed maid and attempting to calm her down.

Amin fears that the maid filmed inside the shelter had developed psychological difficulties after being inside the shelter for months coping with the distress caused by physical or sexual abuse.

"We had a case not too long ago where three women who came back from Saudi Arabia had turned clinically insane,” he says. “These women were tortured so badly, both sexually and physically, that they now carry the physical and emotional scars of their ordeal."

A week before Begum arrived at the safehouse, Akhter witnessed a woman try to take her own life. Middle East Eye has withheld the woman’s name on the grounds of sensitivity.

"There was just so much blood,” Akhter says. “It happened after 11 pm. We were all asleep but then we heard screams and just saw her on the ground bleeding.”

"Nine women were trying to hold down nine wounds. She cut herself on her hands, feet, and, torso. The blood was glistening on the floor. If we never did that, then she would have bled out completely."

Middle East Eye spoke to several women who confirmed this incident took place. They also said that diplomatic officials from Bangladesh had forbidden the women from talking to their relatives about the attempted suicide.

Middle East Eye asked the Bangladesh Embassy in Riyadh and the Ministry of Manpower about the attempted suicide, the safe houses and the women within them. Both had not responded at the time of publication.

Amin is still trying to identify who the woman was so that he can help her. The best he can guess, based on accounts he obtained, is that she came from northern Bangladesh.

He says her case was one of several. "Some women cannot speak anymore, after facing so much torture. The psychological scars they face will take years to heal. This is an epidemic.

“We try to provide the women with access to hospital and pay for treatment. Counselling is also something we try to do to help these women rebuild their lives.”

Middle East Eye asked the Saudi embassies in the UK and US what action it intended to take to combat the abuse of domestic workers in the kingdom and whether it was aware of the safe houses. It had yet to respond at the time of publication.

Dignity is worth more than money

But despite the warnings and reports in the local press of widespread abuse faced by maids in the Gulf, women continue to leave Bangladesh for Saudi Arabia.

“We know girls in our village are going to Saudi. But what can we do? They are just like us. Desperate to get some money and see the world,” a despondent Begum tells MEE.

If I hear about another girl going to Saudi Arabia, I will beat her with my shoe till the idea is out of her head

- Aisha Begum, former domestic worker

Begum's two teenage sons arrive. Taken aback at her first sight of them in a year, she holds their arms and kisses them on the cheek.

Amin hands Akhter a train ticket. She and Begum hug each other, exchange numbers and bid farewell.

Holding her sons with each hand, Begum begins to leave the restaurant. But before departing, she has a final word of advice for women wanting to go to Saudi Arabia.

“If I hear about another girl going to Saudi Arabia, I will beat her with my shoe till the idea is out of her head," she says. “Our dignity is worth more than any amount of money.”

This article is available in French on Middle East Eye French edition.

Middle East Eye propose une couverture et une analyse indépendantes et incomparables du Moyen-Orient, de l’Afrique du Nord et d’autres régions du monde. Pour en savoir plus sur la reprise de ce contenu et les frais qui s’appliquent, veuillez remplir ce formulaire [en anglais]. Pour en savoir plus sur MEE, cliquez ici [en anglais].