Morocco's new coalition: How change of leadership broke months of deadlock

Editor's note: This story was amended on 3 April to correct a quote that was wrongly attributed to Saad Eddine el-Othmani.

RABAT – Abdelilah Benkirane's dismissal as Moroccan prime minister and the appointment of his Justice and Development Party (PJD) colleague Saad Eddine el-Othmani was necessary to break the country's five-month political stalemate, a senior source involved in the coalition negotiations has told Middle East Eye.

Benkirane was dismissed as head of the government by King Mohammed VI, clearing the way for Othmani to form a six-party coalition which was announced last Saturday.

The source told MEE that negotiations had been deadlocked because of Benkirane's refusal to allow a left-wing party, the Socialist Union of Popular Forces (SUPF), to join a coalition, which had been a demand of several other parties.

"Did you understand that as soon as Benkirane left, his party agreed to the participation of the SUPF in the future government?" said the source.

But the NRI and the PM called for the inclusion of the liberal Constitutional Union (CU) and the SUPF, and sporadic negotiations went nowhere.

Games of allegiances

How then did Othmani cross the red line which his predecessor had fixed – and who encouraged the PJD leadership to support Othmani at all costs?

First, a quick reminder. A day after the elections, after having defended the reappointment of the outgoing majority, Benkirane implied that the CU could join the government, as the party linked its fate to that of the NRI by implementing a joint parliamentary group.

But the SUPF chose to join Istiqlal, a conservative formation, in order to negotiate together their entry into the government.

Benkirane then gave an "agreement in principle", a PJD general secretariat member told MEE. "However, several days later, the SUPF joined forces with the NRI. In other words, instead of directly negotiating their participation in the government, they preferred to do it through the NRI in the hope to be better off."

Benkirane then took offence at the tactics of SUPF director Driss Lachgar and decided to exclude the latter from the negotiations agenda.

For Aziz Akhannouch, the president of the NRI, the alliance with the SUPF appeared to offer a way of weakening the PJD's position in the government.

Close to the king, and an appreciated yet feared minister, Akhannouch knows how to blow hot and cold on the political scene, and had been accused many times of blocking the formation of the next government.

He defended until the end the participation of the SPUF, and convinced his PM and CU partners to do the same, and came to be described in sections of the press as the "other head of the government".

"We defend the participation of the SUPF because we consider that without them our position in the government would be weakened," PM secretary general Mohand Laenser said a few weeks ago. He called for "the creation of a comfortable majority, which can ensure the sustainability of the government".

The PJD returned the compliment. "We are the ones who are likely to represent the minority with the participation of the SUPF. Our only real ally within the government is the PPS. The NRI, CU, PM and SUPF form a unit of their own," said an executive from the party.

A decision which is not really accepted

Why should the participation of the SUPF be so important to Akhannouch and his allies? As the main opposition party under Hassan II, the SUPF saw a change in its identity which led it to becoming better known and a party close to the King.

Behind the scenes, people spoke of the "promises from up high, which guaranteed the participation of SUPF in the future government".

If the PJD was delaying announcing the inclusion of the SUPF in the government, it was because "things needed to be sneaked in," one senior figure within the coalition told MEE.

"The PJD suffered a double blow, with the departure of Benkirane and the obligation of including the SUPF. As a result, party leaders needed to sweeten the pill for their electorate," the source said.

While some PJD leaders used their Facebook pages to call for compromises, others saw their willingness to work with the SUPF as a betrayal of the party's principles.

Some PJD activists complained that the move had "not been discussed and debated by the party leaders" and been decided without due process, with one critic calling the accommodation with the SUPF "an additional step towards the independence of the leadership in relation to their core electorate".

"Whilst it has always managed, more or less but always in a clever manner, to manage its individual and collective commitments, the leaders of the PJD have gone too far in pragmatism by failing to justify its decision with its voters," said one observer.

A comfortable 'majority'

Now that the political parties forming the governmental coalition are known, it remains for Othmani to manage the organisational structure of the government and to assign ministerial positions.

Ministers are chosen by the prime minister after consultation with the other parties involved, and then are appointed by the king.

The latter has kept a firm hand on the choices of the executive ministers and can freely accept or refuse the names put forward.

"He knows very well what is at stake," said an expert on Moroccan power struggles. "Indirectly, he has a say over negotiations, often turning politicians against each other and sending messages via his 'special envoys' from the Royal Office or people who are loyal to him."

For strategic ministry posts – the interior ministry, foreign affairs, finance, Islamic affairs - the king often prefers to put in place favoured technocratis appointees.

Just a few days after the nomination of Othmani, rumours abounded of phone calls from the Royal Office to technocrats who will hold strategic offices, asking them not to leave the country before the investiture of the new government.

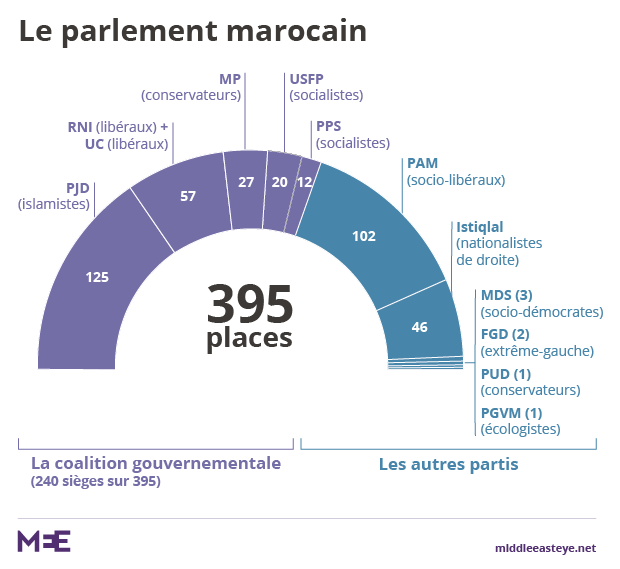

The six political parties which now comprise the coalition have the majority in the House of Representatives.Moderate Islamists from the PJD hold 125 seats, the liberals from the NRI and CU hold 57 seats and the conservative PM holds 27 seats, while on the left the SUPF has 20 seats and the PPS has 12 seats. This equates to a total of 240 seats from the 395 in the first chamber.

"A comfortable majority for the PJD? Nothing could be less sure. We will perhaps be far from a classic opposition, but rather an obstruction inside the government," said a JDP member.

"We have already observed a real and effective coordination between the [opposition] Authenticity and Modernity Party [PAM] and the NRI-CU-PM-SUPF cartel in parliament, especially at the time of election of the president of the Lower House. It remains to be seen whether this will happen again."

The fear of the PJD is to find itself faced with a political unit comprising the AMP and an alliance of smaller parties directed by the NRI. In practice, with their 206 seats in the lower house, these political formations could coordinate on an ad hoc basis to object to decisions and measures imposed by the PJD.

This article was originally published on Middle East Eye’s French page.

Middle East Eye propose une couverture et une analyse indépendantes et incomparables du Moyen-Orient, de l’Afrique du Nord et d’autres régions du monde. Pour en savoir plus sur la reprise de ce contenu et les frais qui s’appliquent, veuillez remplir ce formulaire [en anglais]. Pour en savoir plus sur MEE, cliquez ici [en anglais].