'Ghost boat' mystery: Clues link Egyptian smugglers to tragic sinking

On the night of Thursday 7 April, a group of asylum seekers and migrants were preparing to board a boat in Kafr al-Sheikh, the Nile Delta governorate that has become one of the main hubs of the people smuggling route between Egypt and Europe.

But they were rumbled. Coast guards and security forces caught them and detained them before the small vessel could slip out onto the Mediterranean.

Members of the group, which consisted of 11 Somalis and two others from Ethiopia and Sudan, say the raid may have saved their lives.

Last week, rumours started to spread that hundreds of people had drowned when a ship sank somewhere off the coast of Libya.

According to Muhammad Kashef, a researcher documenting migration trends and immigration detention for the Egyptian Initiative for Personal Rights (EIPR) in Alexandria, members of the group detained in Kafr al-Sheikh believe they were due to join up with the same ship.

“When they went to the coast to catch the boat, they found that the coastguard and military forces were coming for them,” Kashef, who visited the group in the police station where they were being held last week, told Middle East Eye.

“Afterwards, they heard from their relatives in Cairo that a ship had gone down. They believe this was their trip.”

According to Kashef, the group said they had been held for several days in a warehouse about two hours’ drive from Alexandria, a common tactic used by Egyptian smugglers while they wait for the right weather (or security) conditions to get a trip under way.

A larger group is often divided up, before being taken clandestinely to a beach ready for departure. They are then loaded onto smaller boats that convene again at a larger “mothership” further out at sea.

Details about the suspected sinking have remained elusive ever since reports started to surface in the media last Sunday suggesting that between 400 and 500 people may have drowned in an incident involving an overcrowded people-smuggling vessel somewhere off the north coast of Africa.

A relative of a survivor in Mogadishu, the Somali capital, told AFP that a boat had left Alexandria on 7 April, while the BBC quoted survivors describing how they had swam back to smaller boats and eventually been rescued by a cargo ship.

But the Italian and Greek coast guards said they were not aware of a capsizing, while the UN’s refugee agency, the UNHCR, initially tweeted that the reports did not seem credible.

Then on Monday, Italy’s foreign minister Paolo Gentiloni appeared to suggest that reports of a sinking were credible, although only in so far as saying that he was waiting for more details.

“What is sure is that we are again with a tragedy in the Mediterranean, exactly one year after the tragedy we had… in Libyan waters,” Gentiloni told reporters, referring to an incident in which 800 people drowned in April last year.

On Wednesday, the UNHCR said it had interviewed survivors of what it said “could be one of the worst tragedies involving refugees and migrants in the last 12 months”.

“If confirmed, as many as 500 people may have lost their lives when the large boat went down in the Mediterranean Sea at an unknown location between Libya and Italy,” it said.

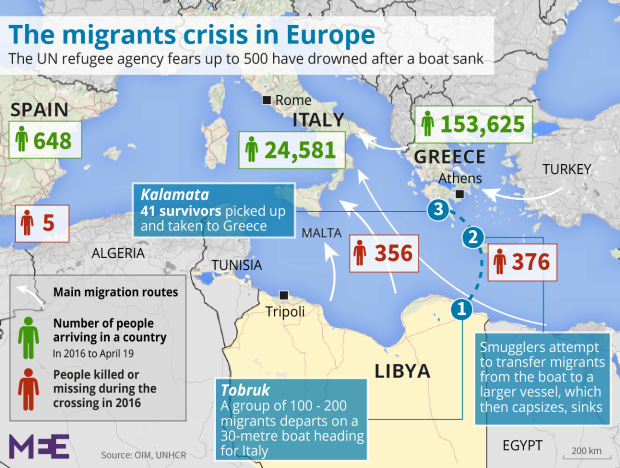

According to survivors’ accounts, between 100 and 200 people had boarded a smaller vessel leaving the eastern Libyan city of Tobruk. After several hours at sea, they had joined up with a “larger ship carrying hundreds of people in terribly overcrowded conditions”.

“At one point during the transfer, the larger boat capsized and sank,” the UNHCR said. “The 41 survivors include people who had not yet boarded the larger vessel, as well as some who managed to swim back to the smaller boat.”

The survivors drifted at sea for up to three days before being spotted and rescued by a merchant vessel. They included 23 Somalis, 11 Ethiopians, six Egyptians and a Sudanese national.

If the involvement of Egyptian boats is confirmed, the sinking would be the worst known incident involving Egyptian smugglers since the alleged deliberate sinking of a boat carrying up to 500 people off the coast of Malta in September 2014.

Funerals for the lost

In Cairo, there have already been funerals for absent bodies lost at sea, including a ceremony for two Ethiopian girls believed to have gone down with the boat, Kashef said.

He said that members of African communities in Cairo suggest that many of the missing hundreds had departed from Hadayek al-Maadi, a dusty Cairene suburb that is home to thousands of refugees and asylum seekers from around the Horn of Africa.

A smuggling simsar (broker) based in the neighbourhood had purportedly helped advertise the trip.

“They’ve admitted that their relatives who were on the boat are dead - they are in mourning,” Kashef said, after speaking to several community leaders in Cairo, who declined to be interviewed by MEE. “But they can’t do anything else… until someone finds the smuggler.”

These stories appear to offer the strongest indication yet that the tragedy may have involved smugglers operating out of Egypt.

Reports of the tragedy come with the European Union anxiously monitoring migration routes from North Africa following a controversial deal with Turkey to stem the flow of people crossing the Aegean Sea.

Many fear the deal will only push people towards other potentially riskier routes elsewhere, such as through Egypt and Libya, putting refugees and migrants in even greater danger.

So far, that does not appear to have happened. The latest UNHCR figures suggest that arrivals in Italy, the principal destination for boats from Egypt and Libya, are down on the same period last year.

But the peak season for irregular migration in the Mediterranean is only just beginning, while the impact of the EU-Turkey deal may take more than a matter of weeks to be felt.

In February, Reuters quoted an anonymous EU official as saying that smuggling in Egypt was becoming an “increasing issue,” expressing concerns about the possibility that smugglers would revive the Mediterranean route from Egypt.

This week, EU border agency Frontex also addressed concerns about the Egyptian route on its website.

Posing the question, “Has Frontex noticed a higher number of departures of migrant boats from Egypt?” the border agency noted that the route had been in use for years, adding: “This is a seasonal route and the number of departures from Egypt increases as the weather improves in the spring”.

Egyptians, predominantly young men and minors, have been taking boats from Egypt’s north coast for years in the hope of better work opportunities in Europe.

However, since 2013 that route has been used by thousands of Syrians and Palestinians from Syria and Gaza, as well as growing numbers from African countries.

Smuggling season

April is generally when Egypt’s irregular migration business sets up shop for the year, so increases in detentions and departures are expected. But some in Cairo suggest that greater numbers than usual are planning to leave this year.

“Last year lots of people successfully made it to Europe from Egypt,” Farhan, a Somali social worker who has lived in Cairo since 2002, told MEE. “So people thought it would be the same this year.”

Farhan said he knew of people in the community who were currently making preparations to cross the Mediterranean.

He said also that growing numbers of “newcomers” with little or no connection to Egypt or Cairo’s Somali community had arrived after being smuggled across the Egypt-Sudan border in the south.

“A lot of them came to Cairo this year planning to take a boat,” said Farhan. “There are lots of people here getting ready.”

According to figures collected by the Egyptian Initiative for Personal Rights (EIPR) in Alexandria, hundreds have already been arrested this year on Egypt’s Mediterranean coast, while thousands have been detained since 2013.

Between April 15-19, 230 people were taken to detention facilities across Alexandria, Beheira and Kafr al-Sheikh, the three governorates spreading out east from central Alexandria, according to EIPR’s figures.

Meanwhile, those who will continue to put their lives in the hands of the people smugglers in the hope of reaching Europe will do so in the knowledge that they could disappear without trace.

Last year, journalist Eric Reidy launched a reporting series about a boat carrying 243 people from Libya’s coast that went missing at sea. All those aboard the “ghost boat,” as it has become known, are still unaccounted for.

“It’s an agonising reality for the families, who often never know for sure what happened to their loved ones,” Reidy told MEE.

“They’re searching for any reason to be hopeful that their loved ones are still alive. Any small piece of information, for them, can be taken as evidence that people might still be alive - so a missed phone call from an unknown number can be interpreted as your lost relative trying to get in touch with you.”

Reidy said that vessels leaving from beaches in Egypt or Libya can lack basic equipment such as radar or GPS used to communicate the locations and movements of shipping around the world.

“So, unless they come into contact with another boat, they’re basically ghost boats – and nobody knows they’re there."

Middle East Eye propose une couverture et une analyse indépendantes et incomparables du Moyen-Orient, de l’Afrique du Nord et d’autres régions du monde. Pour en savoir plus sur la reprise de ce contenu et les frais qui s’appliquent, veuillez remplir ce formulaire [en anglais]. Pour en savoir plus sur MEE, cliquez ici [en anglais].