Britain heads to polls after tumultuous election campaign

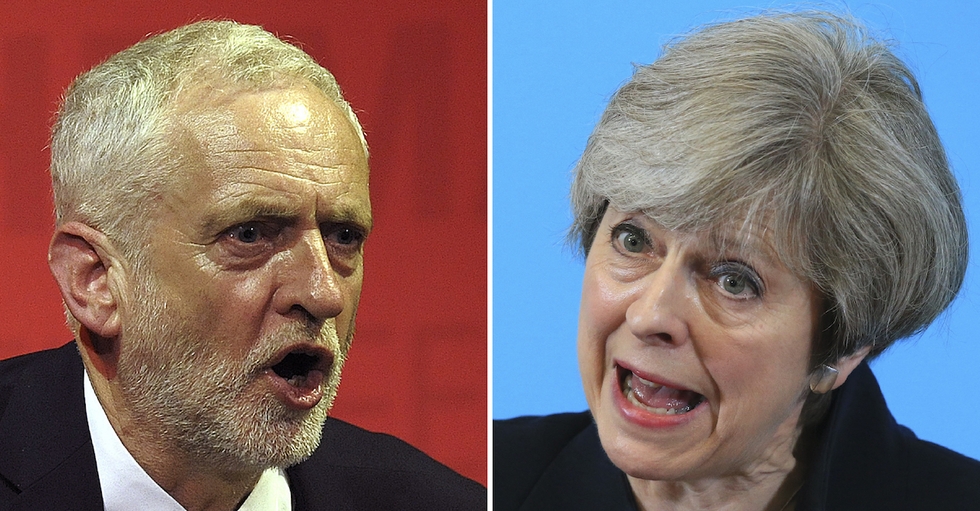

It was all supposed to be so easy. When British Prime Minister Theresa May called an early election on 18 April, it seemed clear what was happening – capitalising on Brexit fever, the new Iron Lady was going to cement the Conservative mandate, increasing her party’s majority in parliament.

But nearly two months - and two deadly militant attacks - later and the self-declared “strong and stable” campaign does not appear to have gone exactly as May planned.

And now, voters head to the polls in what feels like one of the most exciting, and potentially seismic elections in recent memory.

What initially looked like a sure fire Conservative victory now appears to have a far less certain outcome, with many commentators – and some polls - predicting a hung parliament, as in 2010.

Labour leader Jeremy Corbyn had faced much internal opposition before the election was called, and when the poll date was set, many in the top party echelons remained unconvinced he was up to the job.

Within the opposition party there was talk of civil war, with rumours that Corbyn was determined to stay on as leader despite the inevitable crushing defeat. Labour was going to see a loss the likes of which had not been witnessed since 1931, when the party lost four out of every five seats it had previously held.

And the incumbent had Brexit on her side. While she had personally campaigned for Remain, her removed stance seemed to give May the quiet, stoic British distance required of such a task.

May claimed she would steer the UK on the right course, politely navigating Britain’s post-EU future.

But this lack of detail, while designed to feel comfortably reassuring, began to appear less enticing. EU leaders in late May said the PM displayed “completely unreal” expectations about the negotiations.

Opinion polls have come and gone, and it may well be the case that pollsters are again embarrassed – as they were after the last general election in 2015, and the Brexit referendum in 2016 – but they soon began to show growing support for the Labour Party.

As the manifestos were launched, the gap between the two major parties closed even further. Where Labour had detail, numbers and figures, the Conservatives had the lack thereof. Where Labour put social welfare first and foremost, the Conservatives said they wanted to charge older people for their care.

And in an election which was initially so widely seen as May’s for the taking, she seemed to daily grow increasingly uncomfortable.

In the early days of campaigning, one homeowner in the West Midlands told May to get off his lawn. He was merely trying to cut his grass; she was trying to canvass.

Perhaps a minor interaction, but one that seemed to set the tone for the rest of the campaign. As May overstayed her welcome, and trespassed on a lawn just trying to mind its own business, Corbyn soon seemed to relish the ins and outs of the campaign.

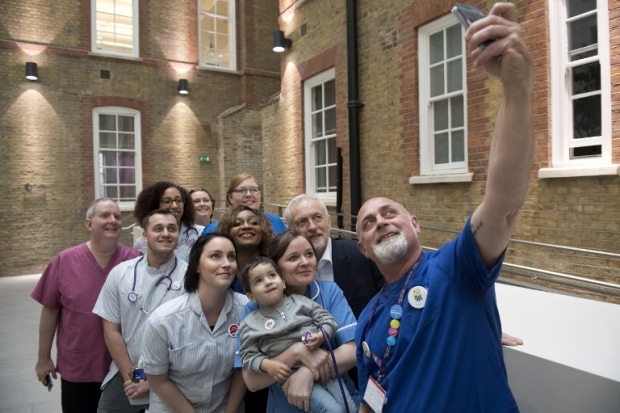

Travelling up and down the country, the Labour leader appeared to grow ever more confident. The country’s top grime artists expressed their support for him, and young people, most likely to vote Labour, registered in record numbers.

Criticised by some quarters for his opposition to Trident, Britain's nuclear arsenal, and his alleged links to Hamas, Corbyn was applauded by others for a "brave and radical" foreign policy.

But a horrific suicide bombing at a pop concert in Manchester in late May quickly brought campaigning to a standstill.

And while no party would have openly wished to capitalise on the attack – which killed 22 people, including many children – security inevitably soon topped the campaigning agenda, and May, home secretary before becoming leader of the party, was forced to answer some difficult questions.

At a televised leader’s debate a week later, however, May was unwilling to make an appearance, instead nominating her Home Secretary Amber Rudd to stand in her stead. Corbyn seemed assured and at ease. Green Party co-leader Caroline Lucas asked Rudd how she could sleep at night, highlighting Britain’s position as second biggest arms exporter in the world – many of those weapons sold to Saudi Arabia, she added.

Just 12 days later, these questions would only become harder when a vehicular and knife attack on a Saturday night in central London killed eight.

An assault on British values, a lapse in security, a matter of policing – through whichever lens one viewed this latest assault, May was again asked to confront some tough issues.

May has taken the opportunity to again call for a repeal of human rights legislation, saying that “enough is enough” and that it is necessary to keep us safe. Corbyn has instead focused on the root cause of such violence, emphasising that he believed British military action abroad is indelibly linked to the threat of terrorism at home.

This general election is viewed not as a choice between centre-right and centre-left parties, but a choice between two diametrically opposed world views.

In what is still, like it or not, a two-horse race, the choice on Thursday looks potentially exciting for the first time in many years.

Middle East Eye propose une couverture et une analyse indépendantes et incomparables du Moyen-Orient, de l’Afrique du Nord et d’autres régions du monde. Pour en savoir plus sur la reprise de ce contenu et les frais qui s’appliquent, veuillez remplir ce formulaire [en anglais]. Pour en savoir plus sur MEE, cliquez ici [en anglais].