Iraqi families still waiting for bodies from Islamic State massacre

TIKRIT, Iraq - The steps of one of Saddam Hussein's former palaces on the outskirts of Tikrit, where the Islamic State group carried out one of its most brutal and shocking massacres in Iraq, reach right down to the water's edge.

In June 2014, just days after IS had seized control of Mosul, so many young Air Force cadets were butchered on this spot that the River Tigris ran red with blood and corpses washed downstream for days. The dusty riverfront slabs are still stained brown from the bloodshed.

"They were new recruits, just young men with no military experience, who thought they were going home for a two-week holiday," said Rathe Mehlif Ali Raadi, clutching a framed photograph of his son Abbas, whom he watched being executed in one of IS's most violent videos.

"I saw his face so clearly on the video," he said, choking back tears as he describes his final, enduring image of his 21-year-old son.

The river is now fenced off. Spiders weave webs over humble commemorations - faded flowers and strips of green fabric blessed at Iraq's holy shrines - tied there by mourning family members of the victims, now confirmed as 1,935 young men, mostly from the poorest areas of central and southern Iraq. Their families rarely manage to visit the site.

An unsteady Nidal Abd Mohammed, shaking uncontrollably, leads a sad route towards the former presidential palace, now lined with large banners of horrifying stills from IS's video of the massacre, widely viewed across Iraq. Some show close-ups of those awaiting execution, the fear of their inevitable fate written across their faces.

They started killing them one by one, while the IS emirs watched from the balcony behind, but there were so many, then they killed them in small groups

- Haidar Attememi, Tikrit Massacre Committee

"They made them walk across this asphalt, boiling hot from the summer sun, in bare feet, then they made them walk round and round. They must have been so tired," Mohammed said, clutching a picture of his son Haider, who was just 19.

"There was a competition between the local tribes to see who could kill the most men, and in the most terrible ways. They took one group up that hill and just hacked them to pieces."

Behind him, a middle-aged woman holding two images of her dead son stands in front of one of the terrible banners, silently identifying her son amongst the doomed men.

Hands tied behind his back, he looks up from his prone position on the ground, while around him his blood-soaked comrades are shot dead by IS militants. Extending her left hand she tenderly touches his cheek, her face full of a mother's love.

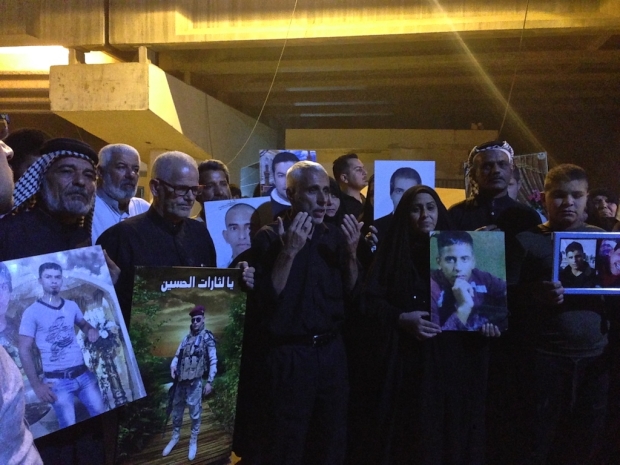

These grieving relatives are amongst 972 families of the victims of the Camp Speicher massacre who, desperate to at least give them a proper burial, are still waiting for the bodies of their dead sons.

Over a five-day killing spree, IS killed the mostly Shia cadets who had unexpectedly been given a fortnight's holiday from the Tikrit Air Academy, also known as Camp Speicher, and been old by their commanders to walk to Tikrit to find transport to Baghdad.

All were unarmed and dressed in civilian clothing. Several trucks owned by locals stopped and offered them a lift to Tikrit but it was a trick. They were instead taken to IS, who grouped them according to their religion and, after releasing some who said they were Sunni, took the rest to the palace complex and started the brutal executions.

One survivor said a fresh group of cadets arrived at the palace packed into yet another truck, and seeing all the blood and bodies tried to flee, creating chaos during which a handful, himself included, managed to escape.

"They started killing them one by one, while the IS emirs watched from the balcony behind, but there were so many, then they killed them in small groups. Then they killed them in other ways, including making the young men lie in freshly dug trenches and just shooting them where they lay," said former head of the Baghdad-based Tikrit Massacre Committee, Haidar Attememi.

The balcony from where IS emirs oversaw the massacre is now lined with framed pictures of some of the dead, in front of which are dried pools of candle wax from past vigils.

At the time, IS claimed to have killed 1,700 cadets, but the number has since been confirmed by the Tikrit Massacre Committee as 1,935. Aside from the bodies thrown into the Tigris, most were buried in mass graves in the palace complex.

Waiting for bodies

Shortly after Tikrit was liberated from IS in 2015, work began on locating and exhuming mass graves around the palace, but the remains of 680 men have yet to be found. To date, 1,255 bodies have been recovered and 963 of those identified through DNA testing, with their remains given to their families.

But remains are often incomplete, and one father said he had received "just four bones and no head," which he found extremely distressing. A further 292 bodies remain in a government mortuary in Baghdad undergoing DNA testing and identification.

"The systems and processes are very, very slow, and we are the only people working on this case now. No one else cares," Hakeem told MEE.

Established by Iraq's Hashd al-Shaabi (Popular Mobilisation) forces, which also has several civilian departments, the Tikrit Massacre Committee works on locating new mass graves, overseeing exhumations, keeping pressure up on the morgue and DNA services, and ensuring all families receive a percentage of their dead sons' salaries.

I want only one thing, and that is my son's body. It is deeply distressing for us not knowing where the bodies of our sons are

- Amal Khadem Alwan, mother

"We have no support other than from the Hashd and we have to fight for everything," he said.

With the mortuary dealing with thousands of cases from across Iraq, Hakeem said most bodies remain in the system for many months. A new UN report said that, across Iraq, 202 mass graves from IS killings have been identified, although just 28 of these have been excavated.

The International Commission on Missing Persons (ICMP), which supports the Iraqi authorities with exhumations and identification of bodies found across Iraq including at Tikrit, explained that identifying bodies was a complex and time-consuming process.

"There is a strategy, which is based on making the most of the limited human resources and capacity of the Iraqi authorities, whilst also ensuring that vital forensic evidence is not lost," said ICMP's global head of archaeology and anthropology Caroline Barker.

"At the Tikrit site, there was a high risk of losing human bodies and forensic evidence near the riverbank, so that was prioritised, but we explained that we would return and deploy a full team to help identify potential further grave sites."

An ongoing lack of coordination and cooperation between different Iraqi authorities and agencies involved in the cases of martyrs, exhumations and identification processes often led to a lack of clarity, especially for grieving families, she said.

"We try to encourage liaison with family members to manage expectations and involve them with the processes, especially the DNA testing, which takes a phenomenal amount of work," Barker said.

Demands for justice

Mother Amal Khadem Alwan, breaking down in tears in Baghdad, said: "I want only one thing, and that is my son's body."

Grabbing her hand, mother Um Amir Ali said: "It is deeply distressing for us not knowing where the bodies of our sons are."

But many family members are equally keen to ensure those involved in the massacre are brought to justice.

Relatives claim hundreds of IS members and Tikrit locals took part in the massacre, some of whom were clearly identifiable in the video. In August last year 36 men were hanged after being convicted of participating in the massacre, in a trial which the United Nations Assistance Mission for Iraq (UNAMI) said fell short of international fair trial standards.

Another 14 were sentenced to death in August this year but, relatives say, hundreds more walk free to this day. Two Iraqis stood trial in Finland accused of killing at least 11 of the cadets but were found innocent and released in 2017.

"Around 100 people have been arrested, but several hundred more are in hiding or have escaped from Iraq," said Samir Azubaidi, official representative for the families for the Tikrit Massacre Committee. His son's body is one of the 972 which remain missing.

"It's not just the killers that need to be brought to justice, but also others who were involved, like the drivers and those who buried the bodies."

Some families believe the massacre in Tikrit - Saddam Hussein's birthplace - was to avenge Iraq's former leader’s execution in 2006.

"We see it as an act of revenge, supported by foreign countries, and we've heard that one of Saddam’s daughters was in Tikrit at the time of the massacre," said father Ibrahim Ahtan, who is still waiting for the body of his son Abbas.

Azubaidi said the perpetrators were all from tribes close to Hussein's, including many former Iraqi army officers and generals.

"We asked some of the captured criminals who participated in the massacre about it and one said they chose that location because the palace was an icon of Saddam's regime and they wanted to make a statement to Iraq and the world avenging Saddam's death," said Attememi.

"They think Shia must be punished for changing Saddam's regime."

Several mothers, including Um Amir Ali, insist the perpetrators of the crime should be executed at the site of the massacre, in front of the families of the men they killed. To date, those given the death penalty for participating in the massacre have been executed in a Nassriya prison, executions which some victims' families attended.

There are also calls amongst victims' families for senior Iraqi commanders to be held to account for sending the young men, unarmed and alone, from Camp Speicher into a volatile Sunni area.

Whilst hoping for more international support to help speed up the processes of exhumation and identification, the Tikrit Massacre Committee and the families it represents want the international community to acknowledge the Camp Speicher Massacre as a "Shia genocide" and to ensure it is recorded in history as such.

"We see this as a 'Shia genocide,' and there is evidence because, in the film, IS made the boys pray and they singled out those who prayed in the Shia way and released most of those who prayed in the Sunni way," Azubaidi told MEE. A few terrified Shia cadets also claimed to be Sunni and were released.

According to Azubaidi, 96 percent of those killed in the massacre were Shia, with the remaining four percent being Kurds and Sunni Muslims.

Middle East Eye propose une couverture et une analyse indépendantes et incomparables du Moyen-Orient, de l’Afrique du Nord et d’autres régions du monde. Pour en savoir plus sur la reprise de ce contenu et les frais qui s’appliquent, veuillez remplir ce formulaire [en anglais]. Pour en savoir plus sur MEE, cliquez ici [en anglais].