Students on strike: Why Tunisia's education reforms have run into trouble

TUNIS - Sana, Sirine, Selma and Wala are all students at the Bourguiba high school in downtown Tunis, attending second year classes (equivalent to the US tenth grade) with a major in Science. Their high school is a pilot, welcoming elite students.

Despite their young age – they are all 16 - they say that they are already aware of the necessity of changing the educational system of their country, which according to them, “does not meet what’s necessary.”

“Classes are overcrowded! Ours, for example, has 28 students,” Sana told Middle East Eye. And that’s why they are on strike.

'We have been on strike since last Monday to call on the ministry to reduce the homework and workload'

- Sana, student

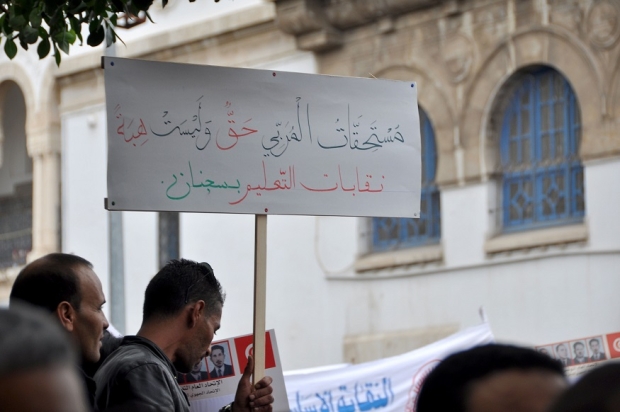

On Wednesday (30 November), secondary and primary education unions called for a national gathering in front of the headquarters of the ministry of education and the government palace. For the past few weeks, students across the country, like these four girls, have been joining protest movements. Interruptions of classes have also been organised in several schools.

During the last strike, organised last week by the Student Movement, an organisation born in the city of Sfax last year, colleges and high schools pupils across the country, from Bizerte and Kasserine to Tunis, took to the streets.

They are protesting at new reforms introduced by the ministry of education. The professors are also demanding the payment of the new school year (2016) bonus, as well as the premium given for the supervision of exams and overtime pay.

“We have been on strike since last Monday to call on the ministry to reduce the homework and workload,” said Sana and her friends. “The changes brought in by the minister in the aftermath of the calls to review the reforms, especially those relating to homework, did not help. In fact, the opposite happened.”

Sixty exams in one school year

These reforms were introduced by the government during the summer to change the education system established under the old regime, altering among others the school holidays schedule.

Until last year, students studied for three trimesters, followed by a week of exams. With this new reform, students will have a two-semester system with a continuous examination system, i.e. about three exams each week. That means that some 60 exams are scheduled during the school year.

These radical changes, which have not affected the content of school curricula dating from the old regime, displease both pupils and teachers.

The high school students interviewed by MEE complained at the pace of eight hours of classes per day, three days a week, plus five hours of classes the other three days. That comes to 39 hours of class in total.

“My parents drop me off in the morning at 8 am and I go home at about 7pm each day,” said Sana. “How do you expect me to study when I'm tired all the time? Because I go home late, it is impossible for me to revise in the evening at home!”

“Our parents feel that we are exhausted and unable to study with such a rhythm, but they can’t do anything,” continued Selma.

Power struggle between trade unions and ministry

According to Nadim Hedhli, senior professor of philosophy at a high school in Bizerte, these reforms prevent students from focusing during classes.

“During my philosophy class, my students are not focused because they think about the exam they will do in the afternoon,” he told MEE. Nadim, who has been teaching twelfth grade students for six years, explained that these changes cause discomfort and mismanagement of the time allocated to classes.

“With this system of continuous examination, in my subject for example, I am obliged to ask other professors to give me an hour of their daily time to organize an exam, as I need three hours for an exam. But I only have two hours of classes per week per class.”

'Students in the second year of high school who major in science have a total of 14 subjects to study, not to mention preparations and other research work'

- Wala, student

He also believes that the curriculum is overloaded and that with this reform, it is impossible to complete it.

“Students in the second year of high school who major in science have a total of 14 subjects to study, not to mention preparations and other research work,” Wala complained.

But for the ministry, these reforms are essential to raise the standard of high school graduates and improve their training. Minister Neji Jelloul said: “The skills acquired by Tunisian students and the performance of the education system in Tunisia are catastrophic. Last year, the success rate at the Baccalauréat was 44.88percent.”

Two months after the start of the school year, the students found themselves amid a power struggle, opposing unionists from the education sector and their ministry.

For the secondary Education Union affiliated with the Tunisian General Labor Union (UGTT), the decisions taken by Jelloul disrupted the work of the reform commissions. Unionists criticised the minister for his unilateral decision-making and his various comments in the media, when he accused professors of inciting students to organise strikes. He also questioned the quality of the work of professors and teachers, which was not to the unionists’ liking.

For their part, students asked the education minister to proceed “step by step, but above all to consult us because we are the first concerned,” Sana and her friends said.

Education: 15 percent of the state budget

The anger is the same inside Tunisia. Mongi Hamdi is a teacher in Laayoune, near Kasserine, in the west of the country. A town known as the poorest of the region. He has been doing this job for the past 18 years and believes that the problems encountered on a daily basis have always been the same.

“In addition to overcrowded programs, schoolchildren carry heavy bags on their backs,” he said. He is a union member himself, and noted that a quarter of the teaching staff since the start of the school year have been supply teachers. More than 40 supply teachers have been placed in some 20 primary schools in Laayoune.

'It is an unprecedented failure because the reforms which have been introduced do not meet the real needs on the ground'

- Mongi Hamdi, teacher

Indeed, the ministry of education did not carry out any new recruitment for teachers, at any level, during the last school year, according to the union, whereas it had pledged to recruit 800 supply teachers last September.

“The ministry is determined to postpone their recruitment until January 2017,” said Lassad Yacoubi, secretary general of the secondary education union. But the union refused and asked for their immediate recruitment to help fill in the vacancies.

“This year is the most catastrophic I've seen since the beginning of my career,” he told MEE. “It is an unprecedented failure because the reforms which have been introduced do not meet the real needs on the ground.”

The budget allocated to the education sector in Tunisia represents 15 percent of the state budget and has benefited from an increase of 200,000 Tunisian dinars (82,000 euros). But 96 percent of this budget (a figure given by the Minister) is devoted to paying teachers’ salaries.

Translated from MEE French: http://www.middleeasteye.net/fr/reportages/tunisie-critiqu-es-par-tous-les-r-formes-ducatives-mettent-en-p-ril-l-ann-e-scolaire

Middle East Eye propose une couverture et une analyse indépendantes et incomparables du Moyen-Orient, de l’Afrique du Nord et d’autres régions du monde. Pour en savoir plus sur la reprise de ce contenu et les frais qui s’appliquent, veuillez remplir ce formulaire [en anglais]. Pour en savoir plus sur MEE, cliquez ici [en anglais].