Egypt's army: The conscripts who refuse to serve

Amir Eid is one of the hundreds of thousands who took to the streets of Cairo and other Egyptian cities during the revolution of January 2011.

Intelligent – he works as a freelance architect in Cairo – and thoughtful, he witnessed scores of people being attacked or even killed during the turmoil which has swept the country during the past five years.

'I personally cannot imagine myself carrying a weapon and shooting at someone'

- Amir Eid, conscientious objector

The following summer Eid, 25, participated in a summer school programme with the Cairo Institute for Human Rights Studies (CIHRS) – and came across NoMilService, a group against the compulsory military service which all Egyptian males are expected to observe.

Eid had thought about being forced to join the army many times – but his involvement at the CIHR got him thinking.

"How can you be part of an organisation that you don’t support?” he said. "I personally cannot imagine myself carrying a weapon and shooting at someone."

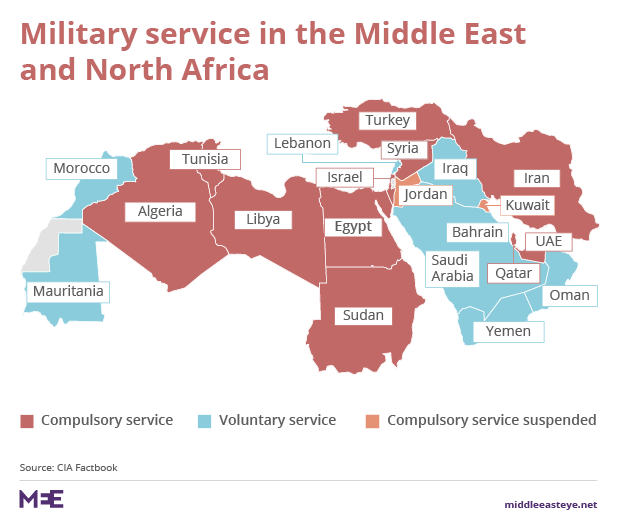

Eid is one of just nine young men in Egypt – a country with a population of about 85 million - who are known to have refused compulsory military service in the past few years.Egypt is a nation where the army has, traditionally, enjoyed a lot of support. Military service is mandatory for men aged 18 to 30 for one to three years, depending on their education. Exemptions can be granted on medical grounds, if the would-be conscript is an only son, has dual nationality or supports his parents.

International law prohibits detention as a punitive measure for conscientious objectors – but in Egypt those who refuse can be jailed. Skipping conscription is not uncommon: openly rejecting it is.

'I first tried the easy way, it didn’t work'

Looking calm and speaking quietly in a Cairo cafe, Eid explained his far from easy story.

He graduated from Cairo University’s faculty of engineering two years ago – and hoped to receive one of the very few army exemptions which allow students to continue post-graduate studies abroad (many do not then return till they are 30).

When he applied for military service in May 2015 as required, he cited personal reasons for not wanting to join the army. The officials suspended his recruiting process and a lengthy investigation then followed.

"I first tried the easy way," he told MEE. “It didn’t work. Then I decided to take the hard path - so I made my objection public."

In a statement of refusal that he posted online on 15 October, he said: ‘’I am not against the army as an entity, but I refuse the fact that the army organisations can exploit me for what is against my principles, morals and belief in peace.”

'I first tried the easy way, it didn’t work. Then I decided to take the hard path - so I made my objection public'

- Amir Eid, conscientious objector

Two weeks after going public he received a phone call from an army officer who asked why he had not turned up on the date of his enlistment.

I’m an objector, Eid told him.

The officer responded that he would need to report to the army two days later or he would be considered a "deserter".

Eid countered that he could not be a deserter in law since he had not yet joined the army.

What were his plans, the officer asked him.

Eid said that he would send letters to the prime minister, the minister of defence and the president, asking to be exempted from military service.

How to live in limbo

Talking about conscription is a taboo subject in Egypt. Those who have served are reticent to discuss their experiences, fearing a backlash from the army. Even human rights groups in the country are wary of giving statements in case they are punished by the courts (rights groups based in Egypt refused to discuss the matter with MEE). And for the local media, reporting on the issue is a red line they refuse to cross.

But although rare, Eid’s case is not the only one.The most well-known conscientious objector is Maikel Nabil, an atheist activist of Coptic descent, who founded NoMilService in 2009. The first known Egyptian to refuse to attend compulsory military service, he was detained for one day in 2010 and eventually exempted on mental health grounds. He was subsequently jailed on several occasions because of his political activism and now lives in exile in the US.

Then there are the cases of Mark Nabil Sanad and Mostafa Ahmed El-Saied, who were permanently exempted in 2015 after more than a year of struggling for recognition. While the Ministry of Defence didn’t recognise them as conscientious objectors, it decided nevertheless to exempt them from service permanently.

Samir El-Sharbaty, like Eid, is in legal limbo. He filed his request to demand exemption from the service in March of this year, is currently under investigation and has not received an answer yet.

"Thousands of Egyptians try to get around the military service every year," he explained.

"I don’t know how we, conscientious objectors, are supposed to live!" El-Sharbaty once wrote.

Eid regards such restrictions as running against international norms. Confidently, he cited international and national legislation that recognise freedom of belief and conscience, including under Article 64 of the Egyptian constitution, which guarantees freedom of belief to all citizens without limits; and Article 18 of the International Convention of Human Rights stipulates that "everyone has the right to freedom of thought, conscience and religion."

Accepted for study in Italy - but can't leave Egypt

Eid’s family initially rejected the notion of conscientious objection, then came to accept his decision. Friends, both in and out of the army, have been very supportive, he said, and encouraged him to go ahead with his case.

He rejected the idea of being subject to the forced labour imposed on conscripts such as his friends, who are obliged to work at least 14-15 hours every day for military-run businesses – a situation Eid considers "slavery".

'I don’t know how we, conscientious objectors, are supposed to live!'

- Samir El-Sharbaty, conscientious objector

"Many tell me they wish they were brave enough to declare themselves objectors," he told MEE. “One friend, who’s doing his military service, says I have the right to opt out since there’s no good in what he goes through daily."

Inspired to do the same, several of Eid’s friends are watching to see the outcome of his case. Then they will decide what to do.

While aware that he could be jailed for his refusal, Eid remains hopeful that he will be exempted. He has been accepted by the Polytechnic University of Milan to do a master’s degree course, which was due to start in September – but he can’t leave Egypt.

Instead he retains a positive outlook, studying independently and pressing forward with his case.

"I will keep getting my story out, and ask for my rights, even if I have to resort to going to court."

Middle East Eye propose une couverture et une analyse indépendantes et incomparables du Moyen-Orient, de l’Afrique du Nord et d’autres régions du monde. Pour en savoir plus sur la reprise de ce contenu et les frais qui s’appliquent, veuillez remplir ce formulaire [en anglais]. Pour en savoir plus sur MEE, cliquez ici [en anglais].