Egypt's economic crisis: Now it's hurting marriage plans

Walaa is a thirtysomething looking forward to getting married: taking part in the ceremony, greeting her guests, setting up home with her new husband. The problem? Walaa lives in Egypt, and is getting married amid an economic meltdown.

“My friends had everything when they got married,” said the government worker, who did not want to give specific details of her job. “I'm having to do without – I'm just getting by with the basics.”

One of the biggest obstacles facing young people wanting to tie the knot in Egypt is a tradition known as “shabka,” a gift of gold jewellery that the groom buys for the bride. The burden of this added cost has spawned initiatives aimed at ending the tradition, with the message incorporated into Friday sermons in some parts of Egypt.

READ: Egypt's currency in freefall: What it actually means

In that respect, Walaa and her husband-to-be are fortunate: the shabka was bought last year. “Now, [gold] prices have doubled," she said. "It was 300 Egyptian pounds a gram last year. Now it would be 600 Egyptian pounds a gram.”

'My friends had everything when they got married. I'm having to do without – I'm just getting by with the basics'

- Walaa, government worker

But Walaa and her fiance still face several fiscal hurdles before they can start married life. Setting up a new household amid a currency crisis is no easy task. Most furniture is imported from abroad, meaning it must be bought using Egypt's scarce reserves of US dollars.

Sharp rises in electricity costs announced in August had a major impact on household budgets, and Walaa's government salary has decreased annually for the past two years because of cutbacks.Like many others, Walaa took to storing all the dollars she could find ahead of time, rather than depositing them in the bank. But her savings aren't enough: now she is relying on her parents for almost everything she needs for her new life after marriage.

Not for import: caviar and dog food

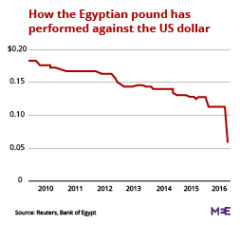

Walaa’s story is similar to many across Egypt, each unique in its own way yet echoing many others. The population, already reeling from a government austerity program, is now confronting the impact of the central bank's decision to float the country's currency in early November, meaning its value can fluctuate according to the international market.

People queued for hours last week to buy petrol before a pre-announced price increase. The move is part of what central bank governor Tarek Amer has said will be a raft of “difficult” austerity measures, implemented amid hopes of securing a $12bn loan from the IMF.

Egyptian economists say the aim of the measure is to get a grip on a rampant black market and pump foreign currency into the official market.

But one black market trader, who spoke to Middle East Eye on condition of anonymity, said that the Egyptian pound is still trading at different rates on the black market to the official banks.

“The banks are refusing to sell any dollars, which is the opposite of what people are saying," he explained. "But mostly they are demanding export licences – that's what's keeping the black market thriving.”

A previous currency flotation in 2003, under the government of Hosni Mubarak, saw inflation to rocket from 2.9 percent to 17.3 percent the following year, according to government figures. The number of families living in poverty also went up by five percent.

The indignity of price fluctuations

With these memories in mind, many Egyptians fear the impact of last week's currency flotation, and are struggling to plan for the future, wondering how to manage their budgets in the short term.

“I buy household goods, fruit and vegetables on a weekly basis,” said Naven, a young woman living in Cairo. “Now I'm surprised every time by the increase in prices.”

A box of 30 eggs, which can be breakfast for a week for a family of five or six, used to cost around one Egyptian pound ($0.89). “The price is fluctuating remarkably,” explained Naveen.

“Once prices have gone up, it's impossible for them to go down to their former level again" she explained. “I'm not the only one – all my neighbours and the other mothers I know are going through this indignity. But we just have to deal with it.”

'Once prices have gone up, it's impossible for them to go down to their former level again'

- Naven, shopper

Traditionally most Egyptian families are headed by the father, while the wife stays at home to raise their children and manage the household. But as Walaa explains: "I will share everything with my future husband to meet the needs of the home, because his salary may not be sufficient to meet the needs and obligations of us living together after we are married, especially in the present circumstances."

Since she got engaged last year, none of Walaa's friends or neighbours have followed suit: instead many of her generation are putting off that special day. “Many of them are scared of missing the marriage train,” she said.

Middle East Eye propose une couverture et une analyse indépendantes et incomparables du Moyen-Orient, de l’Afrique du Nord et d’autres régions du monde. Pour en savoir plus sur la reprise de ce contenu et les frais qui s’appliquent, veuillez remplir ce formulaire [en anglais]. Pour en savoir plus sur MEE, cliquez ici [en anglais].