Water crisis looms for Egypt as Ethiopia's Nile mega-dam nears completion

Editor’s note: Two of the biggest dam projects in the world – one in Turkey, the other in Ethiopia – are nearing completion. Both are likely to profoundly affect the lives of millions in the Middle East and bring further tensions to already severely water-stressed regions.

In his second report, environment journalist Kieran Cooke reports on the progress of the Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam and its likely consequences for Egypt.

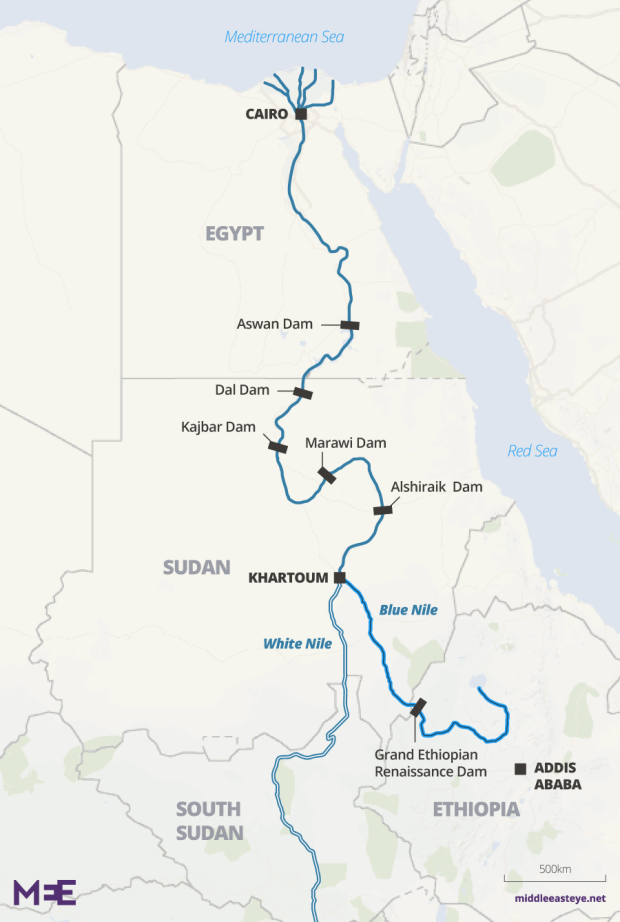

There have been hold ups and reports of large cost overruns but building work on the lavishly titled Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam or GERD, under construction on the Blue Nile in the north of the country since 2011, is nearing completion.

In Cairo, almost 2,500 kilometres to the north, every step in the GERD process – the 6,500 MW hydroelectric dam is one of the world’s largest and the biggest in Africa – is being anxiously watched.

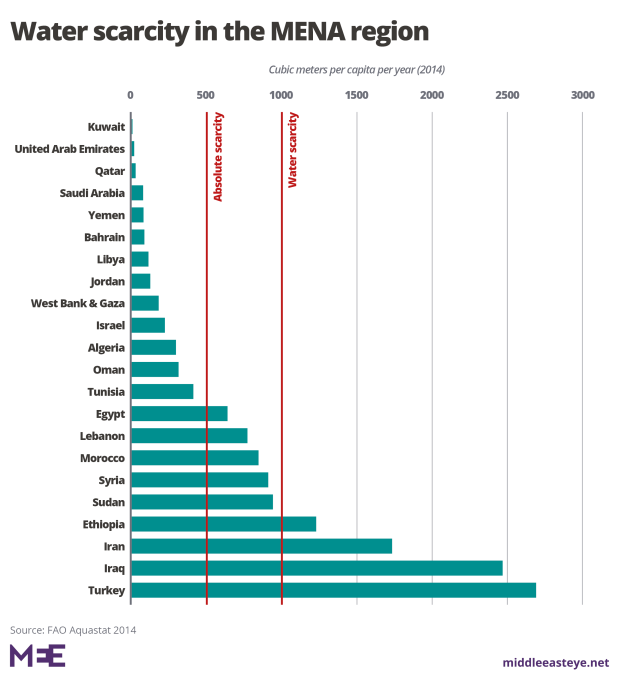

Egypt is facing a water crisis. A rapid increase in demand due to population growth, severe mismanagement of resources and a lack of investment in water infrastructure have led to Egypt being one of the most ‘water stressed’ countries in the world.

At the present rate of consumption, says the UN, the country could run out of water by 2025. The GERD will exacerbate these severe water shortages.The Blue Nile, which rises in Ethiopia, joins the White Nile in Sudan and then flows into Egypt. The river is Egypt’s lifeline with more than 90 percent of its 100 million people dependent on it for drinking water and for irrigating crops.

'It is a matter of life and death… this is our country and water must be secured for our citizens, from Aswan to Alexandria'

- Egyptian President Abdel Fattah el-Sisi

For years Egypt has viewed the Nile as its own; at one stage its politicians talked of bombing the GERD in order to preserve what they viewed as their historical right to the river’s waters.

“No one can touch Egypt’s share of Nile water,” said Egyptian President Abdel Fattah el-Sisi in November last year.

“It is a matter of life and death… this is our country and water must be secured for our citizens, from Aswan to Alexandria.”

Yet for all the strong words, Cairo knows the GERD will, at some point in the near future, become a reality. The project, say close observers of the project, marks a profound shift of power in the Nile Basin.

“Traditionally Egypt – as the power in the region - refused to countenance any upstream dams on the Nile,” said Tobias Von Lossow, a specialist on dams at the Netherlands Institute of International Relations, who has spent years studying the GERD and the complex water politics of the region.

“Then along came Ethiopia and, against all the odds and the doubts of many outsiders, including the Egyptians, the GERD has been built.

“Sudan, the other downstream nation, sees benefits from the GERD and is backing Ethiopia. Egypt has been forced to recognise a new reality – it has to negotiate with Addis Ababa as an equal.”

Electricity shortages

The most immediate concern for Cairo is when the giant reservoir at the GERD site will start being filled, and for how long that process will last.

If the reservoir is filled over a relatively short period – in under five years – it’s calculated that water flows on the Nile through Egypt could drop by as much as 20 percent.

Reduced flows on the Nile would also lead to electricity shortages, with a sharp drop in power generated at the Aswan hydroelectric dam.

Cairo wants a very gradual filling process which will cause less disruption to water flows, taking place over a period of between 10 and 20 years.

Ethiopia on the other hand wants to capitalise on its massive investment and fill the reservoir at the GERD over a much shorter period, enabling it to start generating electricity and begin selling it to other countries.

“The big question is what if the climate changes and there’s a drought during the filling process at the GERD, with water levels in the Nile suddenly dropping substantially,” said Von Lossow. “That could lead to conflict.

“The other issue is that though the GERD is solely for generating electricity, it will regulate water flows on the Blue Nile, enabling more opportunities for the development of agriculture and irrigation across the border in Sudan. That would mean less water flowing into Egypt.”

For the moment, delays and finance problems at the GERD have given Egypt some much needed time to tackle its chronic water woes.

Under the original construction timetable, power was due to be generated from the GERD scheme last year but various factors have been causing delays.

Unwilling to have restrictions placed on it by international lending institutions and banks, Ethiopia has largely self financed the GERD, estimated to be costing $5bn.

Lottery funding

In a nationwide campaign, people were urged to support the project through a national lottery.

Controversially, civil servants were persuaded to use part of their salaries to buy bonds in the scheme. The church also joined in the fundraising.

Then came a sharp downturn in Ethiopia’s economy, with the boom of several years turning to bust. Friendly foreign governments were asked for bail out funds.

The United Arab Emirates supplied $3bn in aid and investments and Saudi Arabia was asked for a year’s supply of fuel, with payment delayed.

China, already a big investor in the country, became a major player in the GERD, with a $1bn loan for power transmission lines.

A new government, headed by prime minister Abiy Ahmed, came to power in April this year.

Ahmed, seen as less nationalistic and more pragmatic than his predecessor, has gone out of his way to address Egypt’s fears about the GERD, meeting Sisi in June this year.

In the course of the Cairo meeting, Egypt’s president asked Ahmed to swear to God “before the Egyptian people” that he would not hurt Egypt’s share of the Nile. Ahmed did so.

“The use of the Nile waters is loosely governed by various historical treaties and agreements though these are often disputed. In the final analysis what often matters is how those in power get on.”

Ahmed has launched an investigation into large-scale cost overruns at the GERD. A company run by the Ethiopian military responsible for supplying turbines and other electrical equipment has been replaced, accused of wasting millions of dollars.

Salini Impregilo, the Italian company and main contractor at the site, is said to be owed considerable amounts of money for its work though it has said little about rumours of long project delays.

Another setback for the project was the death in July of Simegnew Bekele, the project’s chief engineer and a figure much revered in Ethiopia.

Bekele was found dead from a bullet wound in his car. Police subsequently said he had shot himself.

Egypt has begun to take some action aimed at heading off a full-blown water emergency.Under a 20-year water management scheme, plans are for more than $50bn to be spent on desalination plants, including what will be the world’s biggest such facility.

New, less wasteful, irrigation schemes are also being put in place. With an estimated 40 percent of water resources lost due to leakages, more money is being invested in upgrading old piping and in new pumping stations.

Critics say all this is too late, with officials still reluctant to recognize the scale of the country’s water crisis. They say Sisi’s government is obsessed with expensive and questionable prestige projects, such as the construction of a second Suez Canal.

Time, like the water, is running out.

This article is available in French on Middle East Eye French edition.

Middle East Eye propose une couverture et une analyse indépendantes et incomparables du Moyen-Orient, de l’Afrique du Nord et d’autres régions du monde. Pour en savoir plus sur la reprise de ce contenu et les frais qui s’appliquent, veuillez remplir ce formulaire [en anglais]. Pour en savoir plus sur MEE, cliquez ici [en anglais].