Rift widens in Egypt's Muslim Brotherhood after spokesman's sacking

The widening gap between the two major political forces within Egypt’s Muslim Brotherhood has intensified as a split between the movement’s members on their vision for the way forward was made public on Monday.

The spat erupted over a decision to sack the Brotherhood’s spokesman Mohamed Montasser as well as three other senior members, who had been critical of the group for maintaining its status quo "gradual reform" policy towards the state despite a continued government crackdown on dissent, a Muslim Brotherhood member told Middle East Eye on Wednesday on condition of anonymity.

However, the decision to replace Montasser with the Turkey-based Talaat Fahmi was challenged by other members of the Brotherhood, who argued it was "not valid" as it did not follow the standard procedure taken in such cases, the source added.

According to the source, the decision was taken in Egypt by Mohamed Abulrahman, who heads an "investigation committee" recently set up by the Brotherhood’s elected high administrative committee to look into actions of the movement’s members as well as other issues.

But the Turkish Anadolu Agency reported on Wednesday that the decision to sack Montasser was taken in the Brotherhood’s London office, prompting a rejection by 11 administrative officers.

The decision was also challenged by Mohamed Kamal, a member of the Brotherhood's guidance bureau, who insisted in a statement on Wednesday that the high administrative committee did not meet to approve the sacking of Montasser, calling for greater authority to be handed to the movement's youth.

The movement now has two spokesmen and two "official" websites, with the original Ikhwanweb under the control of Montasser’s supporters, while a new outlet - Ikhwansite - was set up recently to serve as a platform for those who recognise Fahmi as their new spokesperson.

While both camps oppose a militant insurgency against the Egyptian state, supporters of Montasser, who are mostly inside Egypt and belong to a younger generation, want a more "revolutionary" stance against the government, seeking to forge alliances to other protest groups and more independence in field decision-making.

Supporters of Fahmi, however, are reported to be predominately exiled older members, who still believe in reforming the system from within, without resorting to radical change in state institutions. This camp also appears to be more wary of any association with violence.

Neither side has suggested breaking away from the Muslim Brotherhood to form a new body, as both camps claim to be representing the views of the movement.

The rift between the two camps has long been in the making following the military coup in July 2013 that toppled elected president Mohamed Morsi, who hails from the Brotherhood.

Middle East Eye reported back in February the existence of jostling between revolutionist and reformist wings of the Brotherhood in how to respond to the government of President Abdul Fattah al-Sisi, following the deaths and imprisonments of thousands of protesters.

"With the Brotherhood’s leaders either in jail or scattered in exile to capitals across the globe, for the first time in the organisation's long history, less known, but revolutionary-spirited members are leading resistance on the ground," wrote Arwa Ibrahim for MEE.

A report published by the Associated Press in June echoed that view.

"The signs of divisions within the group suggest a growing distance between young Brotherhood members who have borne the brunt of street clashes with police and the older Brotherhood leadership, which is largely in prison or in exile abroad and in the past has been willing to strike deals with those in power in Egypt, as means for survival," wrote Maggie Michael.

Gillian Kennedy, a visiting research fellow for the Institute of Middle Eastern Studies (IMES) at King’s College London, also warned in June in an article for the Atlantic Council that "the Muslim Brotherhood appears to be in internal disarray".

She added: "Decentralised and severely damaged by mass arrests and exiled leaders, the Brotherhood now makes decisions without authorisation from the Guidance Bureau, with newly elected youth committees managing the banned organisation."

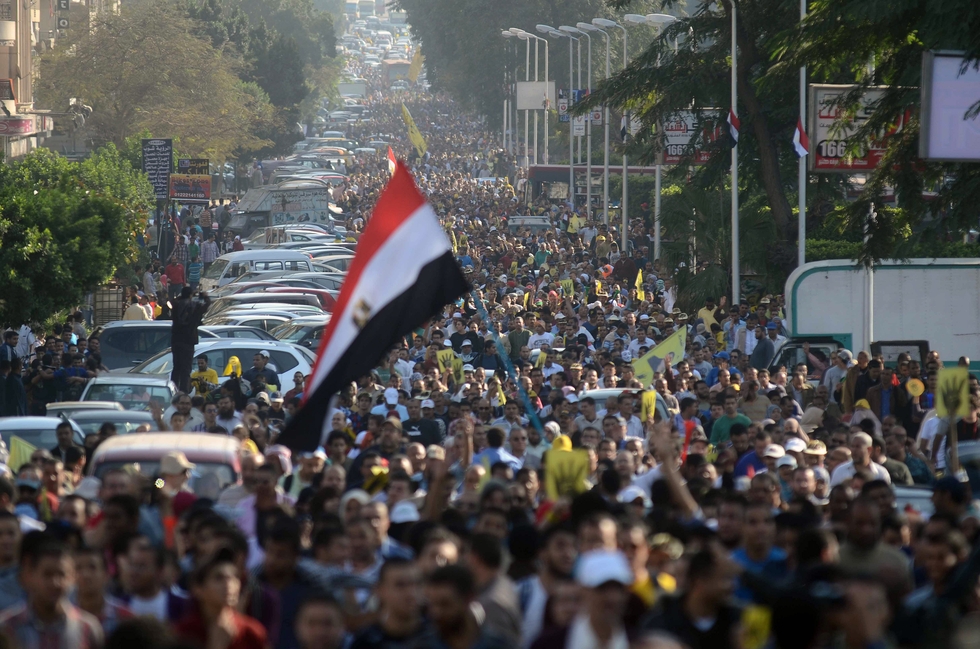

However, it is not the first time that the youth members of the Brotherhood have broken ranks with the movement’s elders. When the 25 January 2011 uprising against the rule of President Hosni Mubarak broke out, young Brotherhood members were among those demonstrating in Tahir Square without being sanctioned by the movement’s leaders.

The youth members of the Brotherhood had effectively dragged the whole movement to be part of Arab Spring revolt that eventually toppled Mubarak and later installed via the ballot box a president from the Muslim Brotherhood. It remains unclear, however, if both sides can manage to mend fences before the fifth anniversary of the 25 January uprising in over a month’s time.

Aside from internal divisions within the movement, the Brotherhood is also at odds with other protest movements, who have thrown - and received - accusations of betraying the "revolution".

Middle East Eye propose une couverture et une analyse indépendantes et incomparables du Moyen-Orient, de l’Afrique du Nord et d’autres régions du monde. Pour en savoir plus sur la reprise de ce contenu et les frais qui s’appliquent, veuillez remplir ce formulaire [en anglais]. Pour en savoir plus sur MEE, cliquez ici [en anglais].