EXCLUSIVE: US drone strike in Syria killed mediator trying to rein in al-Qaeda

A US drone strike which officials said killed a core al-Qaeda leader actually killed a leading Egyptian Islamist who was trying to convince the group's affiliate in Syria to set aside its global ambitions and focus on fighting the Assad government.

Middle East Eye can reveal that at the time of Rifai Taha's death on 5 April, the Egyptian was attempting to persuade Nusra Front fighters face-to-face that their infighting with other rebel groups and focus on emirate-building was damaging the war-torn country.

Taha, a co-founder of the Egyptian militant group al-Gamaa al-Islamiyya, was in Syria to stop infighting that had erupted between Nusra and Ahrar al-Sham, the most powerful rebel group in Syria, over theological differences and territory gained in Idlib in late March, according to two well-informed sources. One was in close contact with Taha days before he crossed into Syria. The other fights for an armed group in Syria.

The source who was in close contact with Taha before his trip said the Egyptian planned to persuade fighters from Nusra, which shares al-Qaeda's vision of a global struggle, to join Ahrar, which believes in fighting only the Syrian government and the Islamic State (IS) group, or at least scale back their al-Qaeda representation in Syria.

Taha was a credible person to carry out this mission, both sources said, because of his influence within al-Qaeda after many years earning the respect of Osama bin Laden and other key al-Qaeda leaders in Afghanistan.

The final moments of the alleged mediator’s life raise key questions over who ordered his death. Taha passed through Atmeh, a crossing into Syria which is only accessible with permission from the Turkish military or intelligence, one of the sources said.

On 5 April, two days after a US drone strike killed 21 people including Abu Firas al-Suri, a Nusra spokesman, in the village of Kafr Jales, Taha met members of Nusra in nearby Idlib city. According to one of the sources, Nusra leader Mohammed al-Golani was present.

Early that evening, residents in Idlib heard the hum of drones overhead. After the meeting ended, Taha drove away in a Toyota pickup which contained an Egyptian commander of Ahrar-al-Sham, Abu Omar al-Masri, and three bodyguards, the source said.

The pickup was hit by missiles as it stopped at a petrol station, and before the men had a chance to get out of the cars. The occupants were “vapourised” by the strike, said one of the sources.

Abu Adnan, a resident and witness interviewed by Bilal Abdul Kareem, an MEE contributor, said he was on his way home from work and was about to pray when he saw three drones in the sky and then heard a series of explosions.

One rocket, as Abu Adnan described it, landed on the Toyota pickup and another on the petrol station. He said five people, including a female bystander, were killed and 10 injured.

Abdul Kareem's video shows body parts and the charred remains of a vehicle, as well as blood spatters on a nearby bus and shrapnel blast marks.

A missile had struck the Toyota where Taha had been sitting, one of the sources said. This suggested that Taha had been closely tracked by the US, which he reportedly confirmed to friends and family shortly before his death.

These accounts differ from the official narrative. A day after the attack, the Washington Post, citing Pentagon officials, reported that the drone had killed “core al-Qaeda” members. A senior US defense official cited in the same report said it was “unclear if the strike eliminated any leadership figures”.

Two days after the Post report, US Central Command said on Twitter that “core al-Qaeda operatives” who threatened US national security had been killed in strikes conducted against the group, referring to both the 3 April and 5 April hits.

Given Taha’s access to the Atmeh border and the precise nature of the drone strike, one of the sources familiar with his trip said he believed the Gamaa al-Islamiyya leader was set up.

“I think he was sent to Syria to die – either by the Turks or his own people,” he said.

Fighters turned mediators

Aside from the mystery over the exact chain of events that led to the drone strike, Taha’s death also raises critical questions about whether the US has blinded itself to a group of Islamists who some believe could rally rebels to work together towards bringing the Syrian civil war to an end and keep them away from a global agenda.

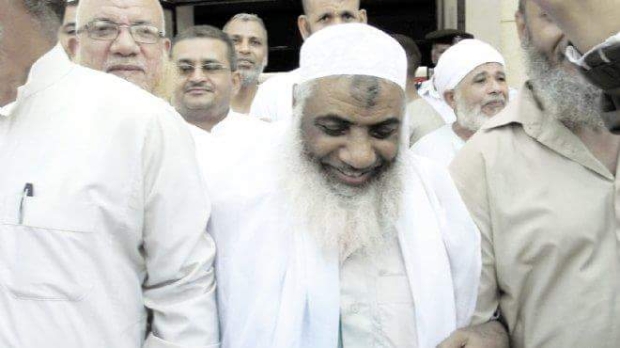

Thought to be in his early 60s, Taha co-founded the Egyptian militant group Gamaa al-Islamiyya in the 1970s. He spent several years in Afghanistan, supporting fighters, and also lived in Sudan. Taha was close to Osama Bin Laden and friends with other al-Qaeda’s leaders, but was not a member of the group, one of the sources familiar with this trip said.

In July 1995, Taha was the mastermind behind a Gamaa al-Islamiyya attempt to assassinate then Egyptian president Hosni Mubarak who was visiting the Ethiopian capital, Addis Ababa, and he was the head of the group’s military wing in 1997 when it killed 62 people, mostly tourists, at an archaeological site in Luxor.

In late 1997, the US State Department added Gamaa al-Islamiyaa for the first time on list of foreign terrorists organisations, where it remains.

Just weeks after the September 2001 attacks, he was picked up at Damascus airport in the CIA’s abduction programme, and sent to Egypt. A member of Gamaa al-Islamiyya, who asked to remain anonymous, told MEE that Taha was tortured over many years, leaving physical and psychological scars.

“They put him under the ground for many years,” the Gamaa al-Islamiyya member said.

A 2005 State Department report on terrorist organisations singles out Taha, saying that he published a book in 2001 advocating mass casualty attacks and then "disappeared" several month later. While members of the group in Egypt renounced the use of violence in March 2002, according to the report, "disaffected" members like Taha might still "be interested in carrying out attacks against US interests".

For unknown reasons, references to Taha are dropped from similar State Deparment reports and discussion of Gamaa al-Islamiyya more recently.

When Mubarak was toppled in 2011, Taha was freed and Gamaa al-Islamiyya formed the Building and Development Party, which won 13 of 508 parliament seats in the 2011 elections.

But soon after Mohamed Morsi, Egypt’s only democratically elected president, was removed in a military coup in 2013, Taha was smuggled into Turkey where he stayed and applied for asylum despite the Turks asking him to leave.

Most recently, he served as the head of Gamaa al-Islamiyya's shura council overseas.

In recent years, as he watched the Syrian civil war unfold from Istanbul, he grew frustrated as Nusra militants alienated Syrians and fought against other rebels rather than working together to oust Assad, according to the two sources familiar with Taha’s Syria visit.

He was also, said one of the sources, concerned about some Nusra hardline element who were ideologically closer to IS.

“He saw the situation in Syria heading in that direction – that people have not learned from what happened in Afghanistan and Iraq and they are just repeating step-by-step the same mistake,” said the fighter in Syria who spoke regularly with Taha over the past year as he planned his visit.

“He could not turn away and just watch.”

‘Soften the urge’

Syria's five-year civil war began as a standoff between peaceful protesters and the government, but quickly morphed into a regional proxy war involving warring rebel factions, Syrian rebels and forces loyal to President Bashar al-Assad. The groups have competed for foreign funding and military support, while on the other hand seeking local support and legitmacy.

To mediate these disputes, high-profile global militants as well as religious scholars have entered the country from time to time to calm fights and finesse alliances – and some, said the fighter in Syria familiar with Taha’s mission, in search of redemption.

“That’s an aspect that the West doesn’t understand – there is this negative notion of the word Islamist or jihadist which needs to be explained and demystified,” he said.

Many of those entering Syria followed ideologies in their youth that they have realised, he said, are not “applicable in all times and space”.

“Some of those trying to fix things are ex al-Qaeda – those are the fiercest ones in attacking al-Qaeda,” he said.

Taha’s visit to Syria came after years of tensions between Nusra and other rebels groups, particularly Ahrar al-Sham, largely over Nusra’s ties to al-Qaeda and the group’s ambitions to build an emirate in Syria, forming a base from which to plot foreign attacks.

Over the past three years, the thinking of Nusra’s leadership has ebbed and flowed over whether – or for some, when - to launch such an initiative. In parallel, there have been on-and-off collaborations between Nusra and other rebels groups on the battlefield.

Last March, Nusra, Ahrar and several others in northern Syria formed an alliance called Jaish al-Fatah – or Army of Conquest. Two months after its formation, the alliance took control of Idlib province.

Several months later, Nusra broke away from Jaish al-Fatah when a new leader, Abo Yehia - less willing to look the other way at Nusra’s connection to al-Qaeda - took over Ahrar, said one of the sources familiar with Taha’s visit.

While many analysts and reports dismiss the idea that Nusra broke away and say that Jaish al-Fatah is led by the group, the source said that Nusra is only leading in the operation's southern flank, with much of the Aleppo operations run by a group called Noredin Zinki.

Earlier this year, after Russia began its intervention in the war, talks between Nusra and Ahrar restarted.

For Ahrar, Nusra’s military power makes the group an invaluable ally on the battlefield in Syria’s north.

For Nusra, Ahrar and other groups bring “a cloak of local legitimacy” upon which the group could “form an emirate eventually that’s sustainable and durable,” said Kyle Orton, a Middle East analyst and associate fellow at the London-based Henry Jackson Society.

According to Orton, talks broke off in February after Ahrar insisted that Nusra end its ties to al-Qaeda and become a fully local group. “As soon as Ahrar said that, Nusra just walked out,” he said.

A month later, Nusra made headlines when it arrested members of the US-backed Free Syrian Army’s Division 13 Brigade, members of which had protected residents of Maarat al-Numan who had been protesting against both Assad and Nusra.

It was in the wake of this uproar that Taha came to town. “The main mission was for him to get people to work together and also to soften this urge for creating an emirate inside Syria,” Hassan Hassan, an associate fellow of Chatham House, told MEE.

He was also, said one of the two sources in touch with Taha before his trip, there to peel off Nusra fighters to join Ahrar which, the source said, he had repeatedly praised privately in recent months.

Empowering hardliners

Similar efforts to rein in al-Qaeda’s Syria branch through co-opting "moderate" members was suggested last year by retired US Army general and former CIA director David Petraeus.

In 2006, Petraeus was in charge of US military operations in Iraq when Americans started paying Sunni groups, some of whom had previously fought the US, to cut ties with and fight al-Qaeda in Iraq as part of the "Anbar awakening".

Two years later, Petraeus told politicians in Washington that the strategy had reduced US casualties, increased security and saved money.

The question in Syria, he told CNN in September, was “whether it might be possible at some point to peel off so-called 'reconcilables' who would be willing to renounce Nusra and align with the moderate opposition (supported by the US and the coalition) to fight against Nusra, ISIL, and Assad”.

Both Nusra and Gamaa al-Islamiyya's designations by the US as terrorist groups would make it difficult – if not impossible - for the US to engage or use someone like Taha directly as a go-between.

But Robert Ford, the former US ambassador to Syria and a senior fellow with the Middle East Institute in Washington, says the US should be talking with Islamist groups who are not on the list, including Ahrar, which advocate that Syrians should decide how their country is ruled in the future.

Ford, who wrote about this strategy last year, said he had given this advice to high-level policy makers, including US President Barack Obama, repeatedly.

“The smart American policy is to engage with groups like Ahrar and Jaish al-Islam that, in turn, are able to peel people away from Nusra and bring them into groups that accept that there must ultimately a political process to decide the future of Syria’s political governance,” Ford told MEE.

MEE contacted the US State Department, Department of Defence and the Centcom military command to comment on Taha’s death and ask whether the US should be considering a strategy similar to that advocated by Petraeus and Ford.

The State Department referred questions to the Department of Defence which did not respond, nor did Centcom.

Distrust of Islamists

Ford said he believes the Obama administration, including policy makers and some analysts advising them, has not attempted this approach because it has “an instinctual distrust of Islamists".

“They have an inability to understand what is a jihadi versus what is a Salafi versus what is a Muslim brother,” he said.

“They don’t see any way for Assad to be removed and so their inclination - if forced to choose between Assad and Islamists – they’ll just go with something secular like Assad, mainly out of instinct.”

And while the US may have listed Nusra and Gamaa al-Islamiyya as terrorist organisations, Hassan, the Chatham House fellow, said regional backers of the groups are interested in supporting the kind of work Taha attempted to accomplish.

“The Americans are not on the same page,” he said.

“[The US military] doesn’t think about what Petraeus thinks. That’s not their strategy. Their strategy is to kill as many of these people as possible, disrupt the leadership, and prevent any sort of coalitions.

"They want to just basically disperse jihadists whenever and wherever they find them.”

Meanwhile, the lack of nuanced understanding, at least publicly, of the differences between Islamists in Syria drives militants to further extremes, said the sources familiar with Taha’s trip. His killing, they said, is an example of the exact ramifications of this broadbrush policy.

"Now after this air strike," said one of the sources, "basically we empowered the hardliners. I am not even sure the US knew who exactly was in the car."

"I’m sure [Taha] was not a friend of the US and the US was not a friend of him,” said the fighter. But with Taha’s mission in Syria "there were common interests".

“What would you like to face – an Islamist group that believes in a national project and a Syria after the war, or do you want to face a group with a global ideology?”

Middle East Eye propose une couverture et une analyse indépendantes et incomparables du Moyen-Orient, de l’Afrique du Nord et d’autres régions du monde. Pour en savoir plus sur la reprise de ce contenu et les frais qui s’appliquent, veuillez remplir ce formulaire [en anglais]. Pour en savoir plus sur MEE, cliquez ici [en anglais].