What is an extremist? UK government admits it still doesn't know

The British government has admitted that it has still not settled on a clear legal definition of extremism, almost two years since pledging to deliver a new strategy to "defeat the extremists".

In a letter published on Thursday, Home Secretary Amber Rudd said that her department was still considering how extremism should be defined, and would hold a full consultation on proposed new legislation before it was introduced.

The letter, which is dated Monday 27 February, was published by the parliamentary joint committee on human rights, whose chair, Harriet Harman, had asked Rudd to update the committee on its long-touted plans for a counter-extremism bill.

A report by the human rights committee last year suggested that the bill had stalled because of difficulties in defining what was meant by “non-violent extremism”.

Rudd wrote in reply: “As your committee report makes clear, this policy area raises complex issues relating to freedom of speech and the importance of having a clear legal definition of extremism.

“These are issues that my department continues to consider and, as you know, we have committed to a full consultation on any new legislation before it is introduced.”

Commenting on the letter, Yasmine Ahmed, executive director of Rights Watch (UK), told Middle East Eye: "The government's admission that it cannot develop a workable definition of 'extremism' it could push through Parliament in this bill should come as no surprise.""Extremism as a concept is subjective and too broad to form the basis of proper government policy," said Ahmed, whose organisation ensures that measures taken by the UK government are compliant with human rights and international law.

But these limitations had not prevented the UK government from launching and extending its counter-extremism Prevent strategy, Ahmed said.

"As case after case arising from the Prevent strategy demonstrates, policies rooted in nebulous terms lead to very real human rights violations," she added.

The government pledged to introduce a new counter-extremism bill in both its 2015 and 2016 Queen’s Speeches, in which it sets out its priorities and proposed legislation for the parliamentary year.

In its last iteration, the government said the bill would give law enforcement agencies "new powers to protect vulnerable people – including children – from those who seek to brainwash them with extremism propaganda so we build a stronger society around our shared liberal values of tolerance and respect".

Theresa May, then home secretary and now Prime Minister, announced a new counter-extremism strategy in March 2015 in which she pledged the government would “tackle the whole spectrum of extremism, violent and non-violent, ideological and non-ideological, Islamist and neo-Nazi – hate and fear in all their forms.

“The starting point of the new strategy is the emphatic rejection of the misconception that in a liberal democracy like Britain, 'anything goes', the belief that living in a society like ours means there aren’t really any fundamental rules or norms. Instead, the foundation stone of our new strategy is the proud promotion of British values,” May said at the time.

'Extremism in all its forms'

In a speech later on Thursday at the annual dinner of the Community Security Trust, an organisation which monitors anti-Semitic hate crime, Rudd said the government remained committed to challenging extremism "in all its forms".

"We must deal with those who promote hatred, intolerance and violence," said Rudd. "That’s why in 2015 this government introduced our Counter Extremism Strategy which focuses on four pillars: building partnerships with all those opposed to extremism, countering extremist ideologies, disrupting extremists and building cohesive communities. All these areas of work challenge extremism in all its forms – from Islamist to the far right."

The government’s Prevent counter-terrorism strategy currently defines extremism as “vocal or active opposition to fundamental British values, including democracy, the rule of law, individual liberty and mutual respect and tolerance of different faiths and beliefs”.

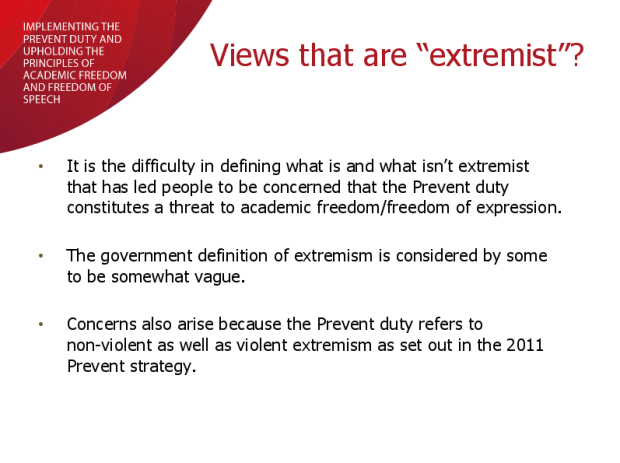

Public sector workers including doctors, teachers and university staff are already required by the Prevent Duty introduced in 2015 to monitor people vulnerable to extremism, despite complaints about the vagueness of the term.

Critics have long argued that efforts to outlaw extremism, and to conflate non-violent extremism with the threat from terrorism, is legally problematic.

Middle East Eye last week revealed how a Prevent training presentation for university staff acknowledged concerns that the government's definition was "somewhat vague".

Writing to Rudd last month, Harman said: “The Government gave us no impression of having a coherent or sufficiently precise definition of either ‘non-violent extremism’ or ‘British values’. There needs to be certainty in the law so that those who are asked to comply with and enforce the law know what behaviour is and is not lawful.”A Home Office spokesperson said: “Legislation to tackle extremism is being considered within Government. We will consult fully on any legislation before it is introduced.”

Middle East Eye propose une couverture et une analyse indépendantes et incomparables du Moyen-Orient, de l’Afrique du Nord et d’autres régions du monde. Pour en savoir plus sur la reprise de ce contenu et les frais qui s’appliquent, veuillez remplir ce formulaire [en anglais]. Pour en savoir plus sur MEE, cliquez ici [en anglais].