Fear and exhaustion in the Old City of Hebron

HEBRON, Occupied Palestinian Territories – Under a makeshift tent, seated on a plastic chair in front of a brazier, 50-year-old Mufid Sharabati watches Israeli soldiers at the Shuhada Street checkpoint in Hebron.

“My three-year-old child … all I can tell you is that he saw three martyrs from the window of our house. What can I do for him? What can he be thinking now? And my 10-year-old son, he filmed the murder of one of the martyrs. He saw the soldier placing a knife near him [to insinuate that it was an attempted attack]. They died at our door with my children at the window.”

The tent has been set up near the checkpoint that has closed off a section of Shuhada Street in the part of Hebron that is under Palestinian Authority (PA) control.

On one side of the street, there is a ghost city with hundreds of closed shops, where 400 Israeli settlers and 50 Palestinian families live, along with 2,000 soldiers charged with protecting the settlers. On the other side is a bustling market-city, one of the main economic centres of the West Bank.

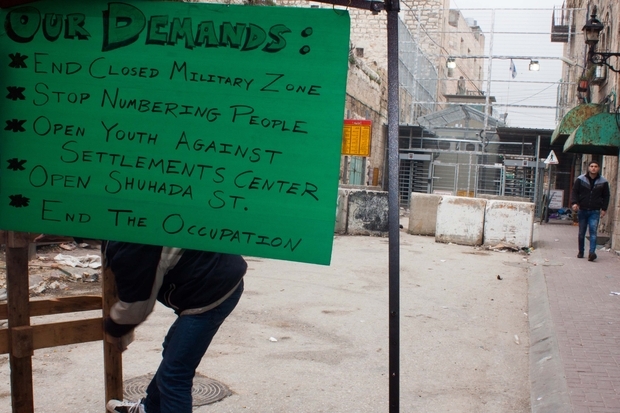

Since 7 January 2013, activists have been demonstrating in front of the checkpoint to protest the military-ordered closure of Tel Rumeida, a neighbourhood situated on the other side of the checkpoint, where Sharabati and his family live.

'Everything is forbidden'

Demonstrators set up a protest tent at the location where where Sharabati’s wife, Wafa, was arrested, detained and accused of possessing a fake ID. The soldiers had reportedly opened her bag and threatened to put a knife inside.

“They wanted to execute her near the Ibrahimi Mosque,” said Sharabati.

“There have been more than 11 martyrs in the area,” he continued. Since October 2015, 11 Palestinian youths have been killed at various checkpoints of the Old City after being accused of trying to carry out attacks against Israeli soldiers and settlers. This rise of attacks on settlers and soldiers in the West Bank has been the pretext used by the Israeli authorities to close Tel Rumeida.

Only Tel Rumeida residents can now enter and exit this neighbourhood. International volunteers who had lived there to monitor the acts of the soldiers and settlers, in addition to journalists and even the relatives of Tel Rumeida residents, have all been denied entry.

This year marks the 22nd anniversary of the closure of Shuhada Street, which Israel enforced in 1994 following the massacre of 29 Palestinians in the Ibrahimi Mosque by American-Israeli settler Baruch Goldstein on 25 February. Sixteen checkpoints have been set up around the Old City since then.

‘Women suffer the most’ at checkpoints

While journalists are not allowed to enter Tel Rumeida through the official checkpoint, there are alternative ways. One of them, through the neighbours’ gardens, leads to the house of Faysa, 40, and her husband Emad Abu Shamsiyeh.

Their house, encircled by fences to protect its inhabitants from settlers, has a military guard tower on top of the roof. On one side of the house is a concrete wall that opens on to the main road of Tel Rumeida. Further up the road is a sentry box and, even further up, is an Israeli settlement.

Sat cross-legged on her sofa, Faysa said that women suffer the most from checkpoints and harassment by Israeli soldiers.

“At the checkpoint, they don’t have female soldiers. They insist to search our bags. And if there is something personal inside? If the woman has her period?” she said.

“If they see something private, they make fun of it and laugh. Not all of them speak Arabic. The old [soldiers] used to speak a little bit Arabic, but these ones, they don’t. Sometimes they shout at the women, they insult them, [and at] other times they eye them up.”

For Faysa and Sharabati, normal life depends on the possibility of getting out of Tel Rumeida. There is a small shop for food, but for other supplies and to visit family, they have to cross the checkpoint. Since last October, though, venturing outside the checkpoint could mean being left outside it indefinitely if it is closed as a result of clashes.

“You have to think twice before going to see your family [outside of Tel Rumeida],” explained Faysa, “because we usually leave the children at home, but then you don’t know what may happen. If I go out with my husband, my heart remains [with the children]. I am afraid that someone will enter the house and attack them or shoot them.”

Faysa expressed anger over the deaths of young Palestinians at the checkpoints. “They either disappear as martyrs or go to prison - they gain nothing out of it,” she said.

For her, these actions, as she calls them, are politically useless. “We are governed by two different regimes: Israel and the Palestinian Authority. If you go out of the Israeli authority, you stay under the Palestinian one. To whom would I give my son? To the Palestinians? And what will they give me in return?”

She continued: “Sometimes, I think about it too. But I can’t help from thinking: for whom should I leave my children? Should I sacrifice my soul? For whom?”

Her words were indirectly addressed to her 18-year-old daughter, Madeline, who sat on the sofa opposite her mother. Madeline, who recently got engaged, is studying to become a nurse.

“I constantly think about her and I am worried about her. But she does not think the same,” said Faysa. “She thinks that her mother wants to control her and prevent her from going out, but no, I fear that the soldiers or the settlers will kill her at any moment. If she moves her hand, if they suspect her, they could kill her immediately. She could be killed as simply as drinking water."

'Family has lost the most'

Faysa regularly gets together with the women of Tel Rumeida through a small local group in an attempt to heal the community.

“We organise trainings about violence, what to do so that the children feel better ... All they see in the street is violence. There is nothing but violence … We discuss the feelings of the youth; we tell them they shouldn’t do everything they see [in the media].”

For her, it is about preserving lives. “Everyone is free to think the way he or she wants, but in my opinion, this uprising, this movement, I am against. Every day, young men, women, children are arrested. And tell me which Arab country has lifted a little finger? Tell me who said ‘I support the Palestinians’? ... Everyone has lost. And family is what has lost the most. It is over.”

Even though she expressed little hope, Faysa supports the demonstrations that take place at the checkpoint. For Sharabati, the protests act as the only way to resist. “This is our situation, as you can see. We stand at the door and people ask for resistance.”

The demonstrators, meanwhile, have placed a large white canvas on plastic chairs, which lean on concrete blocks set up by the army just two or three metres away from the checkpoint. Art students from the University of Hebron will come to paint in solidarity with the residents of Shuhada Street.

“We see painting as part of resistance ... As you can see, it is a peaceful and human campaign,” Sharabati insisted.

Moments later, soldiers ventured out of the checkpoint and removed a photography exhibit hung on the doors of a long-closed shop. Following the soldiers’ order, the demonstrators moved their tent a dozen metres away.

Some soldiers held tear gas canisters, ready to fire them into the crowd, but the situation remained calm.

Once the demonstrators moved on, the soldiers went back to the checkpoint and the art students pull out their brushes.

This article was translated from Middle East Eye's French page

Middle East Eye propose une couverture et une analyse indépendantes et incomparables du Moyen-Orient, de l’Afrique du Nord et d’autres régions du monde. Pour en savoir plus sur la reprise de ce contenu et les frais qui s’appliquent, veuillez remplir ce formulaire [en anglais]. Pour en savoir plus sur MEE, cliquez ici [en anglais].