In 'liberated' Fiskaya, the Turkish state is no friend

DIYARBAKIR, Turkey - Mustafa Chukur describes Fiskaya, a suburb of the southeastern Turkish city of Diyarbakir, as a “liberated” area.

“The people who live here are full of anger. All families in this region have had one relative killed by police or soldiers. If police or military come and put pressure on these people, they will not be able to control themselves.”

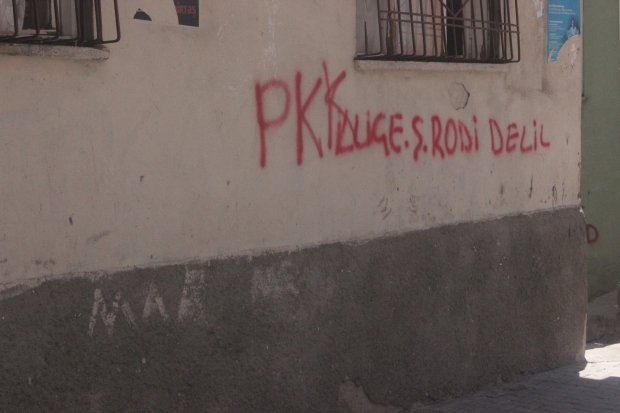

Seemingly every wall bears the graffiti of a political faction – PKK, denoting the Kurdistan Workers Party, YPG, the People Protection Units fighting in northern Syria, YDG-H, the PKK's youth wing and the names of martyred fighters.

The poverty and dilapidation is stark - tiny streets are surrounded by concrete houses, many in disrepair. Windows are reinforced by iron bars, placed there in large part to deflect projectiles. Locals say police rarely pay a visit to the neighbourhood without carrying large quantities of tear gas.

Mistrust between the Kurds of Fiskaya and the Turkish state runs very deep. The majority of the inhabitants of the suburbs are former refugees who fled from the villages neighbouring the city in the 1990s after the Turkish military began a campaign to depopulate Kurdish areas that could be used by the PKK as sources of support, food and supplies.

"The day before our village was emptied, it was shot by artilleries from 5km away," said Chukur, who also works for an organisation that helps the former village refugees.

"The day of emptying the villages, the special forces came with the village guards of other villages," he said, referring to Kurds who agreed to work for state-sponsored militias that collaborated with the military.

"They put guards on the doors of the houses and forced them to leave the village. If they do not leave, they burn the houses. People left the villages with whatever they could take."

"Until that time, nobody joined the PKK from our village," he added. "After those pressures began, young people began to join."

The deforestation and depopulation of the Turkish countryside by the military caused the destruction of over 3,000 Kurdish villages and created 2 million refugees between 1992 and 1995.

Large numbers fled to the wealthier, Europeanised west of the country where they often came under attack from ultra-nationalist Turks who made no disctinction between Kurds and the PKK, locals said.

"We as Kurds want a common life with Turks but at this point Turks aren't ready for this," said Chukur.

"When one of our relatives die, during the ceremonies their relatives call for peace. When a Turkish soldier dies, during the ceremony they call for revenge."

Many others came to Diyarbakir - known to Kurds as Amed - where they were often forced into squalid living conditions or shacked up with relatives.

"It was economically, socially and culturally available for us," said Chukur. "The other sides of the city are very expensive, we cannot stay there – but this side is cheaper. And the people here support us."

For 15 years, Mustafa Chukur and his family could not return to their villages which was continuously blocked off by soldiers and roadblocks. But following the declaration of a ceasefire between the PKK and the ruling AKP, some families were allowed to return to previously depopulated areas.

"Our association began rebuilding our village" he said. "It was a pilot case for this project.

"But because of the developments in the region, it has been delayed for a while."

The breakdown of the ceasefire last week, following the killing of at least 32 socialists in the Syrian border town of Suruc and the retaliatory killing of police officers by the PKK, means that their village is once again blocked off.

A local fixer said that attempts by foreign journalists to reach the villages at present could potentially lead to either arrest and interrogation by the Turkish security services or a prompt kidnapping by the PKK.

'It's getting harder'

Saadet Kurt, another inhabitant of Fiskaya, points to the bullet holes on her neighbour's house, the remnants of one of the neighbourhood's recent clashes with the police.

"Our neighbour's house was shot by guns. They said that young people were doing this and these families were giving support to them. They threw gas bombs and it was totally burnt," she said, gesturing to the upper floor of the house. "Nearly 20 gas bombs."

Kurt is no stranger to the police. A supporter of the PKK, she was picked up on numerous occasions for alleged recruitment activities.

"It's getting harder. Because they know us, it's harder for us. They threaten us when they see us. When I go to a place carrying a bag, they stop me and open my bag. I say, 'you don't have the right to do this.' They say to me, 'maybe you are a suicide bomber'."

For her, there is no question of the Turkish state's attitude to the Kurds - or their announced crackdown against the Islamic State.

"When I go anywhere, they [the state] know where I am," she said. "IS is coming and exploding himself and they say they don't know where he is, they can't follow him – but they always know what I am doing."

"They said they are fighting IS, but they attacked our camps, a cemetery in Lice, they burnt our forests!"

She also poured scorn on Turkey's new agreement with the US to create an "IS-free zone" in north Syria, the region know to Kurds as Rojava and controlled by the PKK-affiliated YPG.

"I won't believe the agreement until they give practical steps – they say a lot of things, but in practice they are just trying to disable the Kurds."

'Nothing from the government'

Not all of the refugees in Fiskaya are from the 90s intake. Some are more recent. Many arrived in the suburb after fleeing the fighting in Kobane between the PKK-affiliate People's Protection Units (YPG) and the Islamic State (IS).

All 12 members of one family live in a two-room flat in Fiskaya. They have relied heavily on Kurdish solidarity for their subsistence.

"People here give support to us, they give aid to us," said the mother. "We rent this house, but we don't have any jobs. We have some daily jobs. One day there is work, another day there isn't. My husband is a music teacher but has no work here."

"Until now, only people living here gave support to us. Nothing from the government. We are afraid of police activity nearby."

Some are much more frank about the situation. As men interrupted their backgammon games in a local cafe to gather round for a discussion on politics, one local ventured his opinion on the killing of the two police officers outside Diyarbakir which sparked much of the current unrest.

"If you ask me, it was not enough!"

"We are faced with mass killings," he said. "The responsibility for the mass killings is on the AKP's head! If we don't defend ourselves, more situations like Suruc will happen."

The man, who declined to give his name, said he had just finished a 10-month jail sentence for PKK activities, which he denied taking part in.

"I was tortured, verbally and physically," he said. "They transferred me to the hospital – I told the doctors I had been beaten. The police threatened the doctor not to file a report."

A staunch supporter of the PKK, he said that any attempt by Turkey to make in-roads into Rojava would provoke a massive backlash.

"If Turkey tries to enter Rojava, it will be the end of Turkey," he warned. "Our leadership is working for peace – but if they insist on war, our people will get arms and fight."

"We will not let Turkey enter Rojava! It is the brain of Kurdistan and the heart of Kurdistan. We will not let them enter – we will die and we will kill them, but we will not let them enter Rojava!"

For Chukur, little has changed since the height of the war in Turkish Kurdistan in the 90s.

"The unit of the state, the mechanism of the state is the same as it was in the 90s. The state's mentality has not changed. There is a republic and a constitution created with a nationalist mentality. We were waiting for this to be changed - we hoped the peace process would change this. But nothing changed.

"When we add all of this, there is no reason not to relive the situation in the 90s.

"We are just waiting."

Middle East Eye propose une couverture et une analyse indépendantes et incomparables du Moyen-Orient, de l’Afrique du Nord et d’autres régions du monde. Pour en savoir plus sur la reprise de ce contenu et les frais qui s’appliquent, veuillez remplir ce formulaire [en anglais]. Pour en savoir plus sur MEE, cliquez ici [en anglais].