Turkey's future: What AKP's former heavyweights think about referendum

ISTANBUL, Turkey – The dominant force in Turkish politics for close to 15 years now, the ruling Justice and Development Party (AKP) has had some powerful leaders and politicians in its ranks. But over the years as the party changed direction and priorities, some of its heavyweights either chose to gradually withdraw to the side lines – or were cast aside.

Talk abounds that these potentially disgruntled figures – including some party founders and ideologues – might join forces in the longer term to establish a new centre right conservative-leaning party.

But in the shorter term, their stance on the upcoming 16 April referendum, which will determine whether the Turkish presidency is transformed into an office with vast powers, could prove crucial.

Despite making full use of the state’s resources to promote its case, the government’s Yes camp seems to have failed to carve out a clear lead with most polls predicting a tight race.

The AKP will need its own support base to favour the constitutional amendments in large numbers to succeed. The views of the party’s former heavy hitters undoubtedly could influence a section of the AKP support, thereby tilting the outcome of the referendum in one direction or another.

Middle East Eye takes a look at who these heavyweights are, and the indicators that hint at their inclinations towards the proposed Turkish-style executive presidency.

Abdullah Gul

Positions held: President, prime minister, foreign minister, party co-founder

Why he matters: Regarded as the statesman of the Turkish conservative Islamist establishment, Gul has a reputation for a compromise-seeking - rather than confrontational - style of politics. But that does not mean he cannot be ruthless. He was at the forefront of a group of politicians as they broke ranks with the more traditionalist-minded Necmettin Erbakan’s National View movement and established the AKP in 2001.

'We have experienced a Turkish-style parliamentary system and seen its problems. There shouldn’t be a Turkish-style presidency'

- Abdullah Gul, former Turkish president

After completing one term as president in 2014, Gul said he was stepping away from active politics. Many believed he walked away after Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan refused to endorse him as the AKP’s next chairman because he supposedly considered Gul a threat.

In the run-in to this referendum, Erdogan and Prime Minister Binali Yildirim held two separate meetings with former AKP ministers and officials seeking their backing. Gul did not attend either, sending a strong message. He also didn’t attend a campaign meeting in his hometown of Kayseri on 2 April, which he was expected to attend alongside Erdogan and Yildirim.

What he said in 2015: “My thoughts on this topic are already known. These topics need to be debated knowledgably. The type of presidency is important. We have experienced a Turkish-style parliamentary system and seen its problems. There shouldn’t be a Turkish-style presidency. If there is to be a presidential system, then just like in the US where the separation of powers is clearly written down and everything is well defined… if it is based on the basis of supremacy of law like in mature democracies, then no doubt it is also a democratic system.”

Ahmet Davutoglu

Positions held: Prime minister, foreign minister, adviser

Why he matters: The bookish and mild-mannered Davutoglu was not a party founder but his rise through the ranks was spectacular, resulting in him eventually becoming prime minister. Davutoglu was the chief ideologue of the AKP and Turkey's foreign policy. His “zero problems with neighbours” approach was a huge success - until the advent of the Arab Spring. Like most other countries, Turkey was also caught unawares by events in Egypt, Libya and elsewhere and its response was muddled.

'Parliament is the shield and spine of democracy because it is an authority that is very difficult to manipulate'

- Ahmet Davutoglu, former Turkish prime minister

Davutoglu was chosen by Erdogan as the party’s candidate for prime minister in 2014 when the former took up his role as president. However, Davutoglu’s belief in a “strong prime minister, strong president” system where both were on an equal footing was not to Erdogan’s liking and he was forced out of office as a result.

The promise to shift to an executive system of presidency was dropped from the AKP’s campaign in the run-in to November 2015’s general election, when Davutoglu was at the party’s helm. Like Gul, Davutoglu also didn’t attend the two meetings called by Erdogan and Yildirim in the lead-up to this referendum to attract the support of former AKP ministers.

What he said in January 2017: “It is a requisite that the legislature and executive proceed on solid ground built around the principles of separation of powers… I conveyed my views, evaluation and concerns on the current amendment proposal’s method and content to our president and prime minister in detail … parliament is the shield and spine of democracy because it is an authority that is very difficult to manipulate since it encompasses all of society.”

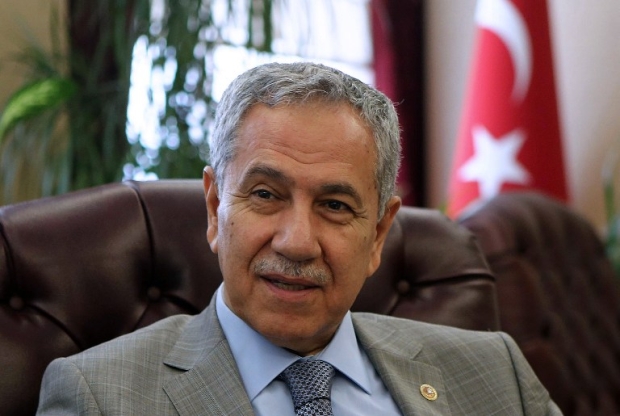

Bulent Arinc

Positions held: Deputy prime minister, parliamentary speaker, government spokesperson, party co-founder

Why he matters: A key cog in the AKP triumvirate along with Gul and Erdogan, Arinc developed a reputation for speaking his mind even if he broke with party ranks. Although he retired from active politics in 2015, he said he would still be willing to assist from the outside.

During his last few years in politics, Arinc contradicted Erdogan publicly on a few occasions. Those remarks are believed to have strained relations between the two and Erdogan allegedly became distrustful of Arinc.

The first time was during the anti-government Gezi park protests in 2013, when Arinc said that engaging in constructive dialogue with demonstrators would be better than reacting with force. There were other outbursts, such as when Arinc said that Erdogan had full knowledge of an agreement reached between government figures and the Kurdish political movement during then ongoing peace process - something Erdogan denied. This spurred speculation that Arinc might be open to aiding or joining a new movement.

Arinc has since been accused of being close to Fethullah Gulen, the US-based preacher accused of orchestrating last year’s coup attempt, by powerful Ankara Mayor Melih Gokcek (Arinc and Gokcek are engaged in an ongoing and long-running feud). Arinc attended the two meetings called by Erdogan and Yildirim.

What he said: He has not commented on the referendum either way, only saying, “speak after the 17th (April)” after one of the meetings.

Fatma Bostan Unsal

Positions held: Deputy chairperson, party founding member

Why she matters: Unsal, a vocal human rights activist and a long-time rights advocate for headscarf-wearing women in Turkey, was dismissed from the AKP in 2016 after signing a petition by academics slamming the government for its actions in the conflict in the southeast of the country. She was also dismissed from her academic post recently via a state of emergency decree for the same reason.

'There are those within the AK Party who are opposed to a concentration of power'

- Fatma Unsal, former AKP deputy chairperson

In the past she has also criticised her own party whenever she felt it was erring. Unsal has said that the current climate of oppression and silencing of free speech is worse than what was witnessed during the period after the events of 27 February 1997. The "post-modern coup" - as it is known - was when the military sent a memorandum to the then-Islamist government in power, demanding that secularism be protected. The government eventually collapsed.

What she said in April 2017: "There are those within the AK Party who are opposed to a concentration of power. One section says let us not mess with the system and not change anything. There is also another section within the party that says fine, let the system change to a presidential one but what happens after Erdogan.”

Ertugrul Gunay

Positions held: Culture minister

Why he matters: The former Republican People’s Party (CHP) member joined the AKP in 2007 - but resigned from the party and his position as culture minister in 2013, criticising how the government reacted to a corruption probe. He also said he was frustrated at the willingness of the authorities to deface historical and cultural landmarks for quick profit.

'I hope and wish that the people of Turkey will not permit the gains of so many years to be destroyed'

- Ertugrul Gunay, former Turkish culture minister

Gunay said the government had reacted by adopting a “defensive psychology” about a corruption probe against Erdogan and his close circle, and that those violating the law would eventually be made to pay a heavy price before the law by the public.

The former minister has been vociferous in his calls for the public to reject the proposed constitutional amendments, saying he hoped a 'No' result would put the brakes on the ruling party.

Gunay said that AKP never publically mentioned an executive presidency system from the day it was formed in 2001 until he resigned in 2013. Rather, he said, the emphasis of the party had always been on a pluralistic democracy, the parliamentary system and a state of law.

He added that fellow citizens from south-east Turkey - the areas where Kurdish communities are most dominant - would not back any slide away from democracy because everyone knows that for Turkey to find permanent answers to its problems then it has to remain committed to democracy. A 'Yes' vote, Gunay said, would be misfortunate for the country.

What he said in April 2017: “I hope and wish that the people of Turkey will not permit the gains of so many years to be destroyed and for the country to be cut off from the civilised world and taken backwards.”

Abdullatif Sener

Positions held: Deputy prime minister, finance minister, party founding member

Why he matters: Sener has become a fierce critic of the AKP since he resigned from the party in 2007 over concerns that his party had strayed from founding principles. He has been actively touring the country, explaining to voters why they should reject the proposed constitutional amendments.

What he said in March 2017: “This is not a presidential system, at least not one as defined in the rest of the world. This [(Turkish-style executive presidency system] constitutes an aberration from beginning to end. No citizen living in this country stands to benefit from such an arrangement…it seems the state will be transformed into a problem-creating mechanism with such an arrangement.”

Ertugrul Yalcinbayir

Positions held: Deputy prime minister

Why he matters: This seasoned politician never served under Erdogan in the cabinet and was deputy prime minister when the AKP first came to power with Gul as prime minister.

Yalcinbayir criticised Erdogan’s style during a party camp in 2004 calling it “democracy via berating” and said: “You berate MPs”. He remained an MP for the AKP until 2007 and has been a vocal critic of the constitutional amendments that would empower the president.

What he said in February 2017: “From now on you won’t be able to witness equality before law. Partisanship will supersede everything… because the head of state is now a party member. It is not possible to accept one person’s rule, one party’s and one clan’s rule instead of adherence to and the supremacy of the constitution.”

Middle East Eye propose une couverture et une analyse indépendantes et incomparables du Moyen-Orient, de l’Afrique du Nord et d’autres régions du monde. Pour en savoir plus sur la reprise de ce contenu et les frais qui s’appliquent, veuillez remplir ce formulaire [en anglais]. Pour en savoir plus sur MEE, cliquez ici [en anglais].