The great Egyptian gas giveaway?

A BP gas agreement touted as a major success at Egypt’s Sharm el-Sheikh economic conference follows two decades of bartering that has seen the British energy giant gain increasingly better terms without producing any gas.

BP and its partner, RWE Dea, are poised to receive 100 percent of any profits, after paying royalties and taxes, from two offshore Egyptian gas concessions, terms that analysts say reflect an Egypt desperate for gas and a sector run incompetently for years.

Bartering that has lasted for 20 years between BP and Egypt’s state-run gas company has cost the country at least $32bn in potential revenue, according to a member of a working group that included employees of BP and the Egyptian state-run gas company who analysed previous contracts.

MEE can reveal that the latest agreement, which lasts for 30 years, says that:

- BP will invest $12bn to develop North Alexandria and West Mediterranean Deep Water, two offshore Egyptian concessions

- BP will sell 100 percent of the gas at between $3 and $4.1 per million British Thermal Units (MMBTU) to the Egyptian General Petroleum Company (EGPC)

- BP will also sell 100 percent of condensate found to EGPC

- BP will pay royalties and income tax only

The agreement shifts away from a production-sharing model, long used by Egypt, in which companies and countries typically split profit 20:80 to a tax royalty scheme that analysts say essentially privatises Egypt’s gas sector and hands control and oversight of natural resources to private companies.

“A decision to give the ownership of the oil and gas reserves, as well as the assets invested, to BP all of a sudden is definitely a move that requires deep investigation by the Egyptian people, represented by a legitimate parliament, to evaluate any advantages this has, if any,” said Hatem Azzam, a former member of Egypt’s parliament who also served as secretary-general of the parliamentary industry and energy committee.

Azzam, whom Egypt officials have said is not welcome back in the country after he spoke out against the July 2013 coup, also warned BP that the deal could be worthless if there was another change in government.

“It is not history yet, and all the agreements the regime is doing in this way are not binding to Egyptians and will be considered null after the military coup is over,” he said.

Energy analyst Mika Minio-Paluello said: “If I was Egyptian, I would be absolutely freaked out about what it means to move away from product-sharing agreements. There is a difference in what is best for the Egyptian state and what’s best for BP and the more control you give to BP in making decisions, the less the public’s interests get represented.”

Others say this is the sheer price of doing business.

“If Egypt had an alternative way of doing it, they could have done it,” said David Butter, a Middle East analyst and associate fellow at Chatham House. “The basic fact is it is going to cost whatever it is going to cost to produce the gas.”

BP has also defended the deal. “The West Nile Delta project investment is the largest foreign direct investment in Egypt, and demonstrates our continued confidence in Egypt and our commitment to unlock its energy potential,” BP told Middle East Eye.

Weak negotiating hand

The deal comes as Egypt finds itself in a weak negotiating position. Starting in 2005, Egypt accrued debts to oil and gas companies that reached $7.5bn as of last June, around half of which was paid off in recent months.

Meanwhile, as gas production slowed down by companies reluctant to invest without clear return, consumption rose and the country transformed from a net exporter to a net importer. By last summer, the season of peak energy use, blackouts became a daily experience for Egyptians, with some areas of the country experiencing up to six power cuts a day, for up to two hours at a time.

To bridge its current gas needs, Egypt imports liquid natural gas from traders at a cost of approximately $10/MMBTU – more than double the amount it will pay BP.

Energy analyst Tareq Baconi said Egypt’s situation is the result of “clear incompetence over years and years of badly managing the oil and gas sector”.

“Egypt used to provide both Israel and Jordan with gas and it went from being able to do that overnight to becoming a net importer,” Baconi said. “The reason that happened was because of the way the energy sector has historically been managed.”

But Egyptian insiders in the oil and gas industry claim that Egypt’s weak negotiating hand is the result of more than just incompetence.

Azzam, the former MP, who has 20 years of experience in the energy industry, said that instead of paying back their debts to multinational energy companies in the 2000s, Egyptian officials spent the money on football teams, shell companies and jobs for relatives and friends.

Many of the same network of officials from the era of former Egyptian president Hosni Mubarak, he said, have been reappointed to positions of influence since the 2013 military coup that brought President Abdel Fattah al-Sisi to power, ahead of the latest agreement with BP.

“It’s recycling Mubarak corruption and presented as if it is an achievement,” said Azzam, who has lived in exile for more than a year after speaking out publicly against Sisi.

This network includes Egypt’s current minister of petroleum and mineral resources, Sherif Ismail, who served as vice minister for gas operations and then as chairman of E-GAS under former minister Sameh Fahmi, he said.

When asked about Azzam’s assertions of corruption in the 2000s, a BP spokesperson said the company was not aware of the allegations raised. EGPC confirmed receipt of an inquiry from MEE, but did not respond to any questions.

Azzam is speaking out now because, while the gas is still in the ground, he said he feels determined that Egypt should get better terms for its natural resources.

“One might not blame BP for this, as corporations always seek to maximise their returns,” he said. “I blame corrupt Egyptian officials that put Egypt in a very vulnerable situation like this, a very exposed situation,” he said.

“We need to make it clear. We still have a chance to renegotiate this and we’ll make all the necessary measures to do this,” he said.

‘Walk near the wall’

For years, Azzam said he heard industry whispers that the agreements between BP and EGPC were “not right”.

After the overthrow of Mubarak in 2011, Azzam was elected to parliament. “My objective in my capacity as secretary general for the industry and energy committee was to put a plan for the future of the energy sector,” he said.

Part of this work, Azzam said, was to review all existing deals which he believed were corrupt in order to start renegotiating their terms to benefit the country and secure more energy resources. As part of this plan, he began to speak in parliament and on television about the deals between BP and EGPC.

“I did this on purpose because I knew when I did this, I would find people that are working in BP or EGPC. They’ll say this guy is supporting the truth and we will support him,” he said.

Employees working in various areas of EGPC and international oil companies, including some in senior positions with legal, contractual and geological expertise, started to speak with him, he said. A small working group was formed and met privately to analyse the deals in detail.

“They didn’t know each other because they didn’t want to be exposed,” Azzam explained. “We have the culture – we say imshe ganbil hait – ‘walk near to the wall’. Keep safe, something like this. Nobody wants to put themselves out, but it’s good enough that when they saw something happening, they got involved.”

By 2012, scouring through past contracts and calculating based on the formulas described within them, the working group, he said, concluded that Egyptians had lost out on at least $32bn in several major renegotiations of the contracts since 1992.

20 years of deals without gas

The history leading up to the West Nile Delta agreement goes back to 1992.

That year, BP agreed to buy 50 percent of the license on the first concession, North Alexandria, from the Spanish oil company Repsol and took on the terms of the agreement negotiated that year between Repsol and EGPC: after the company recovered its investment costs, Egypt would receive 80 percent of the profits and BP would receive 20 percent, according to Azzam.

As part of the agreement, if BP failed to produce gas from North Alexandria by 2001, EGPC would retender bids for the concession, reopening the process to competing contractors, Azzam said. Alternatively, if BP produced gas from certain portions of the concession, the company could hold onto that area, but the rest of the concession would be retendered.

In 1999, BP bid and won the concession to the West Mediterranean Deep Water, an offshore concession adjacent to North Alexandria.

By 2001, when BP bought out Repsol’s remaining interests in the concession - 40 percent of which was, in turn, bought by RWE Dea, then the oil and gas subsidiary of German utility RWE AG - no gas had been produced on the concession, Azzam said. By the terms of the contract, EGPC could have reopened bids for alternative deals.

Instead, with implicit government approval, BP held onto North Alexandria, Azzam said, and, in 2003, EGPC directly awarded the entire concession area to the company without competition, a violation of the 1992 agreement which, he said, would make further development of the agreement “corrupt and void”.

“You should never let a company sit on a field like that,” said analyst Minio-Paluello. “It’s quite standard to say that [if] you don’t do this, we will take it away from you. It should have been one or two or three years, not 10.”

Changing terms

In 2008, BP and RWE Dea renegotiated the terms on both North Alexandria and West Mediterranean Deep Water (RWE Dea holds 20 percent of the West Mediterranean concession).

Azzam said that BP reported at the time that the costs to produce gas from the West Mediterranean, a deep water concession, had been rising, which analysts say was a common concern in the industry at the time.

However, Azzam said the two concessions have different geological qualities that would have required different levels of investment for production, yet the two contracts were renegotiated with nearly identical terms. Basically, he said, Egypt was giving more gas to BP for free.

“Egypt works on a system where the terms are specific to the local license condition,” Mika said. “In that context, having them [the terms of contracts] identical raises questions.”

Under the 2008 terms, after it recovered the amount it had invested to produce gas, BP and RWE Dea would receive 40 percent of the profits and EGPC would receive 60 percent. Egypt was also, by this point, to pay between $4 and $4.50 per MMbtu, up from $2.65 MMbtu contracted in 1992.

“There was no obligation on Egypt to accept, however, they accepted,” Azzam said.

Butter, the Middle East energy analyst and Chatham House associate fellow, however, said with the debts Egypt owed to companies by that time, there wouldn’t have been enough incentive for BP or other gas companies to invest in Egypt without better terms.

“It was already getting up to a few billion dollars in 2008. The payment record of the Egyptians was poor,” Butter said. “They kept on looking for, effectively, loans from the oil companies to delay the payments.”

“It clearly wasn’t enough to get BP playing ball,” he said.

One reason offered for Egypt’s debts is the high cost of subsidising the country’s energy. Such a setup, said Baconi, means that the government is underwriting the costs of power generation companies, so entities like EGPC are always in a precarious financial situation.

But Azzam claimed that Egypt’s debts started to rack up in the 2000s because Egyptian officials were using the money that should have been paid to companies like BP on activities that buttressed their political positions.

Money was used, Azzam said, to buy loyalty from senior officials in Egypt’s fiscal and monitory regulation bodies – including influential ex-army generals and officials - who then turned a blind eye on corrupt oil and gas deals.

Meanwhile, Azzam said that then Minister of Petroleum Sameh Fahmi told the parliament – which must approve all oil and gas agreements – that BP had presented him with a report from international management consultant McKinsey and Company showing that BP’s rate of returns would increase under a renegotiated contract and they would be hesitant to invest otherwise.

“What was his excuse to ask for the change of the agreements? That BP will not invest and we will lose,” Azzam said.

Why, he asked, should Egyptians care about BP’s internal rate of return and why would the country remain at the mercy of BP’s conditions when EGPC had the right to retender the bids?

“These are legitimate questions that have only one answer,” he said. “This is against the interest of the country’s wealth and future generations.”

Terms change again

In 2010, three months after a BP-owned drilling rig exploded in the Gulf of Mexico, leading to Deepwater Horizon, one of the largest marine oil spills to date, BP renegotiated the terms of the two concessions again, announcing that the company and RWE Dea would invest $9bn.

The 2010 contract followed the same production sharing agreement (PSA) model of the earlier deals whereby the companies invested up front and recovered their costs through the sale of petroleum products.

However, instead of splitting profits from those sales with EGPC as in previous contracts, under the new contract BP and RWE Dea appeared to receive 100 percent of the profits after recovering their investment costs, something analysts said is unheard of for this type of agreement in the industry.

“I’ve never heard of a contract where a company gets 100 per cent,” Minio-Paluello said.

“I would say a company getting 100 percent of the profit in a PSA is very odd,” said Baconi.

Baconi, who was hired by MEE to review the 2010 contracts between BP and EPGC on North Alexandria and West Mediterranean Deep Water, confirmed that Azzam and the working group’s conclusion that the contracts – thought to be the most recent until the deal signed last month – left unanswered questions about the profits that Egypt would get.

After recovering the costs of its investment to produce petroleum products on the two concessions, Baconi said the contracts do not say how profit will be split between the company and Egypt.

“After selling a minimum amount of petroleum products to EGPC, Egypt essentially gave BP what could amount to a carte blanche regarding any additional or incremental reserves. The vague nature of the contract suggests this could in effect turn out to be an incredible concession.”

In news reports at the time, BP and Fahmi both explained the change of terms as the price of doing business.

“Under the previous terms,” BP spokesman Robert Wine told reporters “it was not commercially viable for us. The government now has a deal it finds acceptable.”

Fahmi said it was difficult to develop offshore fields in deep water and implied that, without such terms, foreign partners would be loath to produce gas in the country. The contract, he said, offered “great benefits” to Egypt.

Azzam, however, said with Egypt increasingly indebted to BP and with officials continuing to spend ministry funds on corrupt activities, it would have been difficult for EGPC to break off the deal, no matter the terms.

Gas fuels uprisings

Less than a year later, a highly controversial gas deal involving Fahmi would contribute to the uprisings that brought down Mubarak after 30 years in power.

For nearly a decade, Egyptian gas, it came to light, had been sold to Israelis for rock-bottom prices.

Starting in 2005, during Fahmi’s tenure as petroleum minister, EMG – an Egyptian-Israeli company formed by former intelligence figures-turned-businessmen – would buy gas for $1.50 MMBtu and sell it to the Israeli Electric Company for $4 MMBtu. The rate was later increased, but was still below market rates. Egypt lost at least $417m as a result of the deal.

In April 2011, Fahmi was arrested for his role in the deal and, in June 2012, was found guilty on charges of selling cheap gas to Israel and squandering public funds and was sentenced to 15 years in jail.

Also implicated was Hussein Salem, an Egyptian businessman nicknamed the “Father of Sharm el-Sheikh” for his investments that built up the resort town. Salem fled Egypt during the uprisings.

Salem was later arrested at his home in Spain, but was never extradited. He was convicted in absentia and sentenced to 15 years in jail as part of the same trial involving Fahmi.

Despite the importance of Egypt’s energy crisis in the uprisings, under the leadership of the Supreme Council of Armed Forces (SCAF) - Egypt's highest ranking military body, that took power after Mubarak stepped down and held power during most of President Mohamed Morsi’s time in office - many of the same individuals who rose up in the Ministry of Petroleum ranks under, and some as a result of, Fahmi, remained in positions of power and sought to push through the BP deal, Azzam said.

Under SCAF, Abdullah Ghorab, chief executive of EGPC during Fahmi’s time, was appointed oil minister. He sought to restore confidence on the deals, denying the country had waived its stake in the concessions in favour of BP and RWE Dea.

“The BP model was not invented in Egypt,” Ghrab told reporters in 2011. “It is a model that is applied in all countries of the world, and applied in Iraq, for example.”

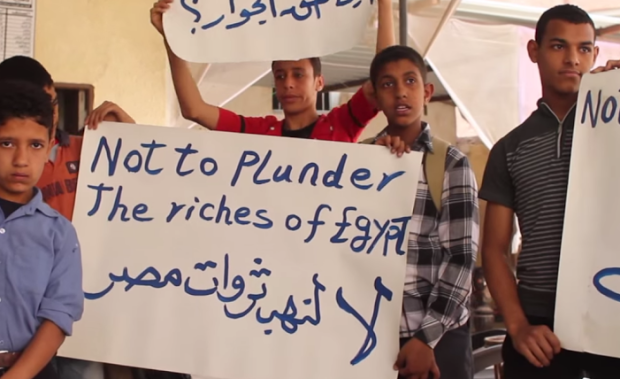

Along with political instability holding up the development of the projects in North Alexandria and West Mediterranean Deep Water, in 2011, residents in Idku, where BP reportedly planned to build an onshore gas facility, started to protest against the plant, concerned about its potential environmental impact.

After Morsi was elected as Egypt’s president in June 2012, Osama Kamal became the new petroleum minister. Kamal, said Azzam, had climbed up the sector’s career ladder with Fahmi’s help, founding and then becoming, in 2009, chairman of the state-run Egyptian Petrochemicals Holding Company, during Fahmi’s tenure.

Azzam, who was then an elected member of parliament and secretary general of the industry and energy committee, said he warned Morsi twice that a Mubarak-era network was still operating behind the scenes, but Morsi failed to take action.

“I personally started to speak about it very high and very loudly in the parliament and outside the parliament and during Morsi’s presence,” Azzam said. “He was not basically informed about [the gas deals] in the right way.”

In May 2013, Azzam filed complaints against both deals with Egypt’s general prosecutor. Several days later, Morsi announced a cabinet reshuffle which saw, among other changes, Kamil replaced with Sherif Hadara who, Azzam said, was not considered to be part of the old guard.

Azzam said he called Hadara on his first day to make him aware of the complaints he had filed. Within days, talks were reopened with BP with the intention, on the Egyptian side, of renegotiating better terms for the country, he said.

Two months later, when a popularly backed military coup brought Sisi to power, Azzam’s case with the prosecutor general was frozen.

Revived BP deal

With Sisi, Sherif Ismail, vice-minister for gas operations and then chairman of state-run EGAS during Fahmi’s time, became the new oil minister. Ismail, Azzam said, endorsed many of Egypt’s gas export deals, including the EMG deal.

In June 2014, Ismail told Reuters that the BP project in North Alexandria had been restarted and vowed to pay off the country's debts to multinationals by the end of the year.

This February, an Egyptian court acquitted Fahmi of all charges and annulled his prison sentence, confirmation in Azzam’s eyes that the old guard had returned.

Then last month, on the same day the agreement had reportedly been signed, Bob Dudley, BP’s CEO, told the Sharm el-Sheikh audience that at a time when the drop in oil prices have been a huge shock for companies like his that had been living in a “world of luxury”, their pledged investment in Egypt is significant.

“We have seen in the last year, and particularly in the last three or four months, the term that many people use in Egypt: we can see the red tape being cut,” Dudley told the audience.

“To make that decision in 2015, in a year where we are not doing that in many other places around the world again should be a signal about the changed business environment in Egypt.”

Azzam, who now lives in exile in Europe, is sceptical about the financial achievements of Sharm El-Sheikh - held at the Jolie Ville Movenpick owned by Hussein Salem, the businessman involved in the Egypt-Israeli gas deal - for the country.

“The only beneficiary so far from the conference is Salem who gets the bookings of the conference area and the hotels,” he said. “This is for sure the only money that this conference has earned.”

And despite public pledges, questions remain: what are the exact terms of the agreement between BP, RWE Dea and EGPC? And will gas finally be produced from North Alexandria and Western Mediterranean Deep Water?

BP says the gas will come online by 2017 and will create 5,000 mostly Egyptian jobs.

The project, BP told MEE, “creates a platform for monetising future resources in the area over the next 30 years or more. Further phases of development of the remaining resources will be appraised in the future.”

After many false starts, said Butter, the project looks hopeful.

“It’s been such a long time, you have to be concerned that maybe some other kind of snag will appear,” he said. “But yes, I’d say that the implementation should go ahead over the next couple of years, so I think there will be some gas coming out there.”

Minio-Paluello, however, questions whether – gas shortage or not – it should come out under the current terms.

“Resources belong to the state and the people. It’s understood that if you get a private company in, they are allowed to make a reasonable return,” he said, “but most of the money should be going to the state because it’s the peoples’ resource and they can only be taken once.”

Azzam is sceptical that a new agreement is even in place.

“There is no parliament now. So if Sisi signed [the agreement], it has to be published. Nobody announced that something has been published so far,” Azzam said.

And even if an agreement had been negotiated, he said questions remain.

“It doesn’t mean anything unless you see the terms and conditions inside. You can name it Hatem Azzam agreement, but it doesn’t mean anything because in 2010, they named it production sharing and basically we got zero,” he said.

“So I would ask the same question: what does Egypt get out of it?”

Middle East Eye propose une couverture et une analyse indépendantes et incomparables du Moyen-Orient, de l’Afrique du Nord et d’autres régions du monde. Pour en savoir plus sur la reprise de ce contenu et les frais qui s’appliquent, veuillez remplir ce formulaire [en anglais]. Pour en savoir plus sur MEE, cliquez ici [en anglais].