Hostage of Europe: Iranian hunger striker protests his treatment by UNHCR

ATHENS – Having escaped political persecution, Iranian Kurd and former engineer Anwar Nillufary may have been granted refugee status in Greece, but he has vowed to maintain his hunger strike until he can be resettled elsewhere.

“I cannot trust them,” says Nillufary, gesturing toward the Athens office of the UN High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR). “I trusted them with my life and look where I am now.”

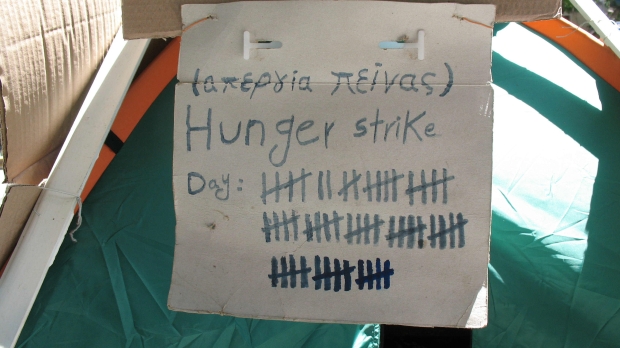

The 31-year-old Iranian Kurd has been camped outside the anonymous and innocuous-looking building for the past 60 days, staging a hunger strike to demand resettlement from the UN body and to protest the lack of protection for others like him seeking asylum in Europe.

'I trusted them with my life and look where I am now'

- Anwar Nillufary, refugee

He is currently back to a liquid-only diet, having broken his fast temporarily a month in after he started bleeding and doctors urged him to eat biscuits.

Nillufary is a recognised refugee with legal status in Greece. His circumstances reflect those of thousands of others there who find themselves within EU borders but on the margins of society, trapped with no legal route out of the debt-ridden country, and even less sense of a future inside.

“This is Europe, but I made a mistake coming here to seek refuge,” says the gaunt civil engineer. “In the past when there were wars, safe passage was made for people to flee, but now EU countries are just taking money to build fences.”

Administrative torture

Before reaching Greece, Nillufary says he experienced psychological torture, and his current situation brings to mind an equal form of administrative torture.

Nillufary left Iran more than 12 years ago, forced into exile in Iraqi Kurdistan due to his involvement in Kurdish political activism.

But he found little relief from repression, intimidation and corruption under the Kurdish Regional Government and was again driven to seek refuge from political violence - as he says, the Kurdish Democratic Party (KDP) took his residency papers and work permit, and ordered him to leave the region by whatever means. As he says: "They destroyed me."

He was stripped of his Iranian passport and denied identity papers by the politically hostile Iraqi authorities, and his efforts to apply for emigration or refugee status in Iraq were thwarted.

Eventually, he resorted to the services of people smugglers to get him to western Europe, but like so many others was abandoned halfway on his arrival in Greece in 2014 - a year before the 2015 peak of the continent’s so-called ‘refugee crisis’.

According to the Dublin regulation in place at that time, refugees were required to apply for asylum in the first EU country of arrival - a protocol of which Nillufary says he was unaware.

“The first time I approached the UNHCR office in Greece wasn’t for staying in this country,” he says.

“I was looking for legal pathways to leave Greece and be resettled elsewhere in the EU.”

As he recounts, he was instructed by UNHCR officials to apply for asylum in Greece which would then allow him to seek resettlement elsewhere.

After months sleeping rough and living with thieves and drug dealers in Athens - many refugees in the city experience such a precarious existence - Nillufary finally received his refugee papers, made his way to Sweden to apply for asylum and found that he had been acting on misinformation.

Wasted journey to Europe

“The first thing they asked me was ‘have you ever applied for asylum elsewhere in Europe?’ I said ‘yes’. They kept me in a camp for three months and finally deported me back to Athens with nowhere to go,” he recounts.

“I was misled. UNHCR played with my life and I have wasted years based on what they said.”

A UNHCR spokesperson could not comment on what he was told by staff at the time, but insists that he is not eligible for resettlement.

Nillufary’s efforts to find a legal route to a life elsewhere have over the two years since taken him to Italy, France and as far as Iceland.

He has written to countless embassies - and even to the Canadian prime minister - requesting asylum and contacted hundreds of foreign NGOs and engineering firms in an effort to gain sponsorship abroad.

In Greece too, he has applied for work in more than 50 companies, without a hint of acknowledgement - an outcome which he attributes to cultural discrimination.

“There are no jobs in this country - refugees go from having a good career and salary to ending up in the hands of smugglers and junkies,” he says.

“We cannot do anything and have no leverage. They can take back their papers and their fake protection - I want to apply for resettlement.”

The UNHCR, however, has repeatedly denied that Nillufary is eligible for resettlement and refused to issue the referral letter required for him to seek asylum elsewhere.

Yet he insists he wants to do things the legal way. “I cannot go back to people smugglers - I am even ready to pay for safe passage,” he says. “But I need to get out of this country.”

According to official government figures, there are around 62,000 refugees and asylum seekers currently in Greece, although the UNHCR and other EU members put the number at around 45,000.

In a country with the highest recorded unemployment in the EU (23 percent) and failing social services for Greek citizens, the outlook for refugees who do not speak the native language and are up against the brunt of racial prejudice is unpromising.

Slipping under the radar

While many languish in dubious conditions at official refugee camps, thousands slip below the radar, living homeless and falling into illegal and exploitative employment, begging and prostitution.

As the advocacy NGO the Greek Forum of Refugees highlights in a statement on Nillufary’s case, the major issues he has confronted - unemployment, insecure accommodation and discrimination - are typical.

“Refugees experience too often the feeling of being trapped in Europe. Reaching the coasts is at the cost of their own lives, but that is only the first part of the journey,” it says, noting the long road that must be taken to reach safety in Europe itself.

'Refugees experience too often the feeling of being trapped in Europe'

- Greek Forum of Refugees

“They are left wondering what does international protection mean if it does not offer the possibility of living a peaceful and normal life?”

These conditions of continued insecurity, deprivation and hopelessness, coupled with the lack of legal routes out of Greece, is pushing many refugees there back to people smugglers.

Spend an hour in the company of refugees in Athens and you will hear countless stories - the odd one successful - of attempts to reach other EU countries on fake passports or clandestinely over borders.

As one young Iraqi man notes of his efforts to raise money for a smuggler to Italy: “I have fled here to find insults and prejudice - my life is at the mercy of organisations.”

Akis Demopolous (not his real name), an activist and lawyer from a local refugee squat supporting Nillufary’s protest, likewise notes the effects of the bureaucratic bind in Greece.

“People are getting angry at refugees here, but they don’t understand that they are trapped,” he says.

“There are thousands like Anwar - the only difference is that he has a voice. He has gone as high as he can through legal routes and nothing has happened.”

Until this week, Nillufary’s hunger strike received no acknowledgement from UNHCR other than recurrent attempts by the police to evict him from his post.

He has been told he is not allowed to camp in the shade of the single tree outside for “security reasons”. When he erected cardboard boxes for shelter, he was arrested and detained for five hours.

'People are getting angry at refugees here, but they don’t understand that they are trapped'

- Akis Demopolous, activist and lawyer

Last week, a community solidarity protest finally pushed the UNHCR to offer a meeting. But while staff invited his advocates inside to discuss his case, Nillufary was told he could not enter the offices: no refugees are allowed inside the building under UNHCR policy, the official stated.

Although UNHCR representatives finally met with him in the foyer, his demands were again refused. As Leo Dobbs, a spokesman for the agency, explained, refugees in Greece have three options available to them: voluntary repatriation, resettlement or integration.

“Resettlement does not constitute a refugee right,” he said. “It is only for select and vulnerable cases and Anwar is not eligible. So we are looking at ways of integration, encouraging him to go down those avenues. Greece is a stable country and there is no apparent threat to him here.”

In order to apply for resettlement, refugees must be either without legal and physical protection, a survivor of torture or unable to integrate in Greece. Although Nillufary claims he meets all three criteria, he has no paper trail to prove it.

Bureaucracy over humanity

Demopolous agrees with the legality of UNHCR’s position, but says that bureaucracy has come to take precedence over humanity in the European asylum system.

“The UNHCR’s logic is that someone like Anwar is privileged to have refugee status,” he says.

“He has been a victim of torture and cannot integrate in Greece, except on paper - but this is all they care about. It is a robotic logic. Sure, maybe he could get a job picking strawberries in a field for one euro an hour and be abused by his employers, but there is no life for him here.”

He has since received visits from doctors from the municipality who have deemed his condition critical and attempted to persuade him to go to hospital. Nillufary has refused and says he will remain firmly in his camp.

“I have been a refugee for over 12 years, as has been confirmed on paper. I have no country to go back to and I cannot stay here,” he says. “But all UNHCR cares about is fulfilling its mandate. It is just torturing refugees in Europe.”

Middle East Eye propose une couverture et une analyse indépendantes et incomparables du Moyen-Orient, de l’Afrique du Nord et d’autres régions du monde. Pour en savoir plus sur la reprise de ce contenu et les frais qui s’appliquent, veuillez remplir ce formulaire [en anglais]. Pour en savoir plus sur MEE, cliquez ici [en anglais].