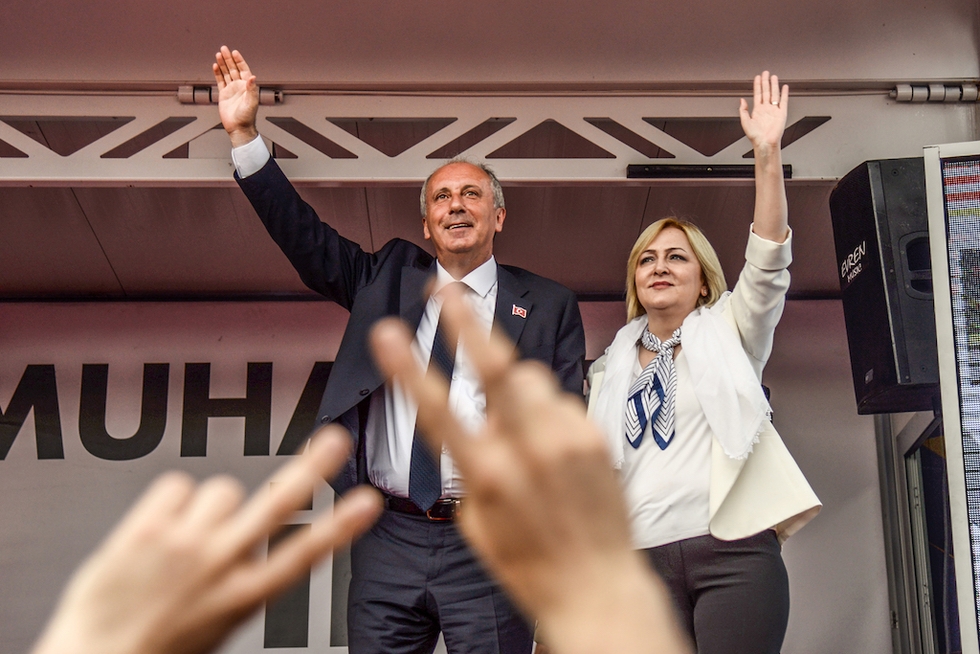

Turkish elections: Is Muharrem Ince the man to challenge Erdogan's dominance?

On Monday, huge crowds gathered in the Kurdish-majority city of Diyarbakir to hear Muharrem Ince speak in support of his bid to become president of the republic of Turkey.

The city is no stranger to large political rallies, having long been a focal point for Kurdish nationalists agitating for greater autonomy or even independence from a state which they claim has long attempted to erase their identity.

What made this rally unusual was that Ince is the candidate for the Republican People's Party (CHP), the organisation that Kurds have historically held most responsible for their marginalisation.

“First, we will teach our children Turkish as a formal language. Secondly, a language spoken with parents at home, whether it is Kurdish, Arabic or Circassian," Ince told the crowd, in his trademark fiery rhetorical style.

"This is not enough. We will make them the citizens of the world, meaning we will teach English, French, Italian, Arabic, Russian, Japanese and Chinese to our children."

The CHP, the party of the republic's founder, Mustafa Kemal Ataturk, has long struggled to reach beyond its core voting base of nationalists and secularists. Since its founding in 1919, the party has been seen as elitist by the religious conservative core of central Anatolia, and as chauvinist and authoritarian by the country's Kurdish minority.

But with those opposing Recep Tayyip Erdogan more determined than ever to overcome their differences to try to challenge the president and his long-dominant Justice and Development Party (AKP), the tables have turned, and in Ince the CHP may have found someone who can break through the religious/Kurdish glass ceiling without alienating its core voter base.

In 2016, he broke with his party's whip and voted against lifting the immunity of members of the People's Democratic Party (HDP), a pro-Kurdish party accused by the government (and the CHP) of having links to the outlawed Kurdistan Workers' Party (PKK).

“How could you eliminate immunity in such a climate in which the judiciary has become subservient to the government?” Ince told the Sozcu daily at the time, warning that if HDP members were arrested then CHP members would be next.

Since being chosen as the party's candidate on 3 May, Ince has publicly called for Selahattin Demirtas, the imprisoned co-leader and presidential candidate for the HDP, to be released from jail so he could campaign. The wives of the two candidates even met in a "solidarity" meeting in Diyarbakir.

The reason why courting Kurdish votes matters is that, should the presidential elections go to a second round of voting, any chance of defeating Erdogan will rest on securing the votes of Kurds - votes which have in past gone to Erdogan.

'He writes poetry, he is interested in physics and science, he speaks about films, he dances the traditional dances of Turkey - it is hard to imagine Erdogan dancing!'

- Ali Tirali, CHP activist

While the ruling AKP had for many years been able to court the votes of the religious and conservative Kurdish voting base, promising both investment for the troubled region and an expansion of Kurdish civil and language rights, the relationship between the party and the community has largely collapsed.

Firstly, because of a brutal conflict in the southwest between the Turkish state and Kurdish militants, which has been waged for decades but has flared up in recent years, leaving at least 3,638 people dead, hundreds of thousands displaced and areas including the historic Diyarbakir neighbourhood of Sur, as well as the towns of Cizre, Sirnak, Nusaybin, in ruins.

Secondly, because of Erdogan's decision to ally with the far-right Nationalist Movement Party (MHP), who have long been the staunchest opponents of Kurdish rights in Turkey.

Although the HDP has been excluded from the parliamentary national alliance consisting of the CHP, the centre-right Iyi Party and Islamist Felicity Party, its parliamentarians have reacted warmly to Ince's openness.

“We are pleased that the opposition’s efforts are so strong. If we do not remain in the second round we will support Muharram Ince,” said Mithat Sancar, an HDP MP.

Aykan Erdemir, an analyst and former CHP parliamentarian, hailed Ince's ability to pursue "a smart strategy of highlighting his humble origins, wit and bipartisanship as the antithesis of the pomp, quick temper and partisanship that have lately come to characterise Erdogan".

A CHP Erdogan?

In some ways equally as difficult for the CHP has been courting the conservative religious voters that make up rural Anatolia.

For the last presidential election in 2014, the party put forward Ekmeleddin Ihsanoglu, a former head of the Organisation of Islamic Cooperation, as its candidate, in a bid to woo the AKP's support base.

While Erdogan only won the first round of the presidential elections with 51.79 percent of the vote, the choice of a conservative as the CHP's candidate enraged many of the party's core supporters. The party suffered further humiliation when Ihsanoglu decided to join the MHP and openly backed Erdogan for the 2018 poll.

Unrest in the CHP ranks was further exacerbated when rumours spread that the party was considering supporting former president and Erdogan ally-turned-critic Abdullah Gul. The party moved quickly to deny the rumours after outcry from supporters and MPs, including Ince himself.

By contrast, Ince is very popular with the CHP grassroots, but the controversy highlighted the difficulties the party faces in trying to court religious conservatives.

Since hitting the campaign trail, Ince has attempted to highlight his "common man" appeal, often appearing to tread the same territory as Erdogan. Like Erdogan, Ince's family derives from the northern province of Rize on the coast of the Black Sea.

In speeches, he has pointed out that his family are religious conservatives, and that his sister even wears the headscarf (an item of clothing long despised by the CHP).

“My sister has been wearing a headscarf... but we do not use it for voting as you did, we will not use it," he said in a 2013 speech.

"Women with headscarves are our sisters too and we’ll not let you use their faith for your political desires.”

With little media coverage in Turkey, Ince's campaigning has been very hands-on - he has traversed the length and breadth of the country, speaking to large rallies and calling on his followers to post videos online to circumvent the heavily state-influenced news outlets.

Ali Tirali, a youth activist supporter in the CHP, hailed Ince as a "Kemalist and social democrat" successfully reaching out beyond the CHP base to appeal to the nation's diverse communities.

"Ince is particularly represented in the international media as the ‘CHP version of Erdogan’, but he is a very different man. He writes poetry, he is interested in physics and science, he speaks about films, he dances the traditional dances of Turkey - it is hard to imagine Erdogan dancing!"

An uphill struggle

Ince faces an uphill struggle. The latest poll released by the Gezici polling company on Thursday indicated that Erdogan was set to get only 47.1 percent of the vote in the first round voting, with Ince on 27.8.

However, were Ince able to gather up the votes of the other opposition presidential candidates then he might achieve what has hitherto been dismissed as a remote possibility by political analysts both inside and outside the country.

Were Ince to actually win, he would inherit the presidency in a highly fractured country, with a looming economic crisis on the horizon.

"Ince's challenge - if he defeats Erdogan in the runoff voting - would be to transform a leader-oriented and top-down political culture into a deliberative and consensus-building polity," said Erdemir, adding that he expected the CHP candidate to delegate to an array of experts while "sharing power with representatives of the wide electoral coalition supporting him".

Tirali, who in the past has been highly critical of attempts by the CHP to put forward candidates such as Gul or Ihsangolu, argued any success for Ince derives from his refusal to simply portray himself as Erdogan-lite.

"He shows that in order to be successful with the right-wing party and get the right-wing votes, you don’t need to imitate right-wing politicians," he said.

"[Previously] we saw the elections and voting patterns as very identity-based and Ince is showing something different. If someone can make the voters believe that he will do better things for the country, he can get their votes. I think that’s very important."

This article is available in French on Middle East Eye French edition.

Middle East Eye propose une couverture et une analyse indépendantes et incomparables du Moyen-Orient, de l’Afrique du Nord et d’autres régions du monde. Pour en savoir plus sur la reprise de ce contenu et les frais qui s’appliquent, veuillez remplir ce formulaire [en anglais]. Pour en savoir plus sur MEE, cliquez ici [en anglais].