Iran's dollar crisis: How Tehran's attempt to kill the black market backfired

TEHRAN - It was meant to stop the value of the Iranian rial from sliding even further.

But an attempt by the government to unify the dollar’s official and black market exchange rates backfired, leaving government ministries and those with official connections to go on a wild shopping spree, at the cost of consumers who were already suffering economically.

It resulted in some strange and illegal buying strategies, according to Iranian media, as companies bought in goods they knew they could then sell on at inflated prices.

Textile companies imported sacks of beans. Auto manufacturers imported tea and coffee machines. Poultry businesses imported Apple iPhones

Textile companies imported sacks of beans. Auto manufacturers imported tea and coffee machines. Poultry businesses imported Apple iPhones. Those phone companies which did buy what they were supposed to simply doubled the price.

In perhaps the most glaring example, the ministry of health, which was supposed to use $21m in government allocated funds to buy ambulances, appears to have imported entirely difference vehicles that no one can now trace.

Iranian economic expert Saheb Sadeghi told MEE: “It is totally strange that the ministry of health has bought cars with subsidised dollars. This is why there are many problems with the supply of medicine in the country.”

Regulation crisis

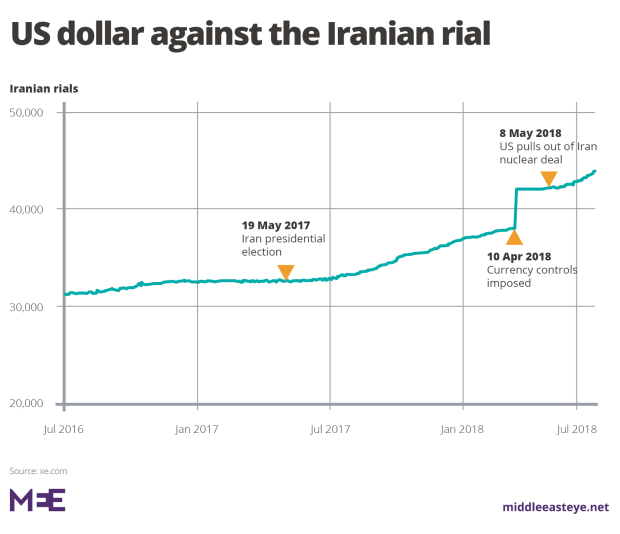

The regulation crisis began in April when the government decided to sell the dollar at a rate of 42,000 rials on both the official and black markets after the rial plunged against the dollar (again), partly due to periodic fears that the US was about to re-impose sanctions.

The move, said Iran’s first vice-president Eshaq Jahangiri, would unify Iran’s currency market which has been traded in a two-tier system for years.

“For us, any unofficial exchange rate on the market will be considered smuggling from tomorrow,” Jahangiri said on 9 April. Those suspected of illegal money exchanges were arrested and faced punishments equivalent to those for drugs traffickers.

As part of its efforts, the government launched an internet platform through which state-sanctioned importers could apply for hard currency at the lower official rate.

But soon it became apparent that the system was not working. Some businesses complained that they had to complete lengthy paperwork to obtain currency and that it took too long.Mohammad Hossein Barkhordar, a member of the Iran Chamber of Commerce, Industries, Mines and Agriculture, said on 22 April: “So far, no importer has been able to register a single order at the rate of 42,000 rials to the US dollar. The continuation of this trend will lead to an increase in prices.”

The government was unable to supply the hard currency that business needed. Iranians hoping to travel or study abroad were also hit.

Many people, desperate for dollars, headed back to the black market that the programme had hoped to end

The result? Many people, desperate for dollars, headed back to the black market that the programme had hoped to end.

The loss of confidence saw the rial plummet even further. The price of the US dollar rose to almost twice the official rate.

Businesses were left with two stark choices: stop work, because of the uncertainty about the availability of imported goods and the confusion about prices – or pay up and then sell the goods on to consumers at higher prices.

Many chose the latter, forcing customers to pay more, as Barkhordar predicted.

Behrooz Mehraban, an importer of eyeglasses from China, told MEE. “It’s not possible to get hold of hard currency [at the official rate] if you do not have any connections with the government.

“You have to rely on the free currency market [or else] you have to go the long route to gain access to foreign currencies on the official market."

Chaotic marketplace

Consumers, meanwhile, were being left to fend for themselves in an increasingly chaotic marketplace.

They were suffering even before the changes were introduced: the rial has already lost a third of its value against the dollar from early 2015 to early 2018. There have been several protests and strikes across the country against inflation and corruption this year.

Markets were already skittish as Donald Trump signalled he wanted to pull out of the Iran nuclear deal, with the re-imposition of sanctions. The past year has seen protests and strikes.

Washington has subsequently declared that it will halt gas and oil imports - the republic’s biggest export - by the end of the year.

Reza Hamidi, an accountant with a private company, told MEE: "I'm currently worried about the future of the country and my own family. The financial condition of the country is not well at all, and the new US sanctions would make the situation worse."

The frustrations eventually came to a head over the price of mobile phones, which had risen by as much as 40 percent by late June, according to Mohammad-Javad Azari Jahromi, the minister of information and communications technology.

You can easily see that companies which have connections [to the government] have been able to gain foreign currency from the government

- Alireza Mahdavi, mobile phone shop owner

The iPhone X, for instance, priced at around $1,000 on foreign markets, should have been sold for 42m rial in Iran. Instead it was being sold at 90m rial – more than $2,000.

Alireza Mahdavi, owner of a mobile shop in Tehran, told MEE: "You can easily see that companies which have connections [to the government] have been able to gain foreign currency from the government.

“They have sold their imported phones at much higher prices than the official rate they had received. Meanwhile, for you as an importer who doesn’t have these connections, it’s very difficult to receive your share of government hard currency."

On 24 June, mobile phone shopkeepers in two main shopping areas in Tehran went on strike to protest at the rapid drop in the value of the rial, then marched towards Iran’s parliament building.

The list indicated that, from 20 March to 25 June, $258m had been allocated to 40 businesses, but only around $88m worth of phones had made it through customs. It meant, according to government statements, that $170m worth of goods were still languishing in customs.

The list sparked controversy among consumers. Soon Iranian online mobile retailers, fearful that they would be accused of taking advantage of the system, removed prices from their websites, instead asking customers to contact them for the latest prices.

Meanwhile, many shopkeepers in mobile shops told customers that they didn’t have any new phones to sell, amid fear they would be accused of also cheating the system.

Name and shame

The mobile phone list left Iranians angered – and also whetted their appetites for details about other sectors.

Protests broke out in Tehran’s bazaar and smaller cities, amid demands that the government name and shame the companies involved.

Their call was echoed by President Hassan Rouhani who ordered the ministry of industry and central bank of Iran on 27 June to release a full list of companies which had received hard currency from the government and what they had done with it.

Industry Minister Mohammad Shariatmadari argued that doing so would “wage a war against the private sector” and cause the economy to collapse.

But amid government pressure, two lists followed. Between them they detailed 1,500 companies and agencies, how much hard currency they had managed to obtain and what they had done with it.

The details were an eye-opener, revealing major corruption. And they sent shockwaves through Iran.

Iranian economic expert Saheb Sadeghi pointed out that the abuses could be even worse, given that the list did not include the powerful state-owned car companies which have a stranglehold on the market because of the high tariffs paid on imported foreign vehicles.

Sadeghi said that an estimated $30bn worth of currency was taken outside Iran in 2017, amid fears of the collapse of the Iran nuclear deal and a cut in interest rates. The country, he said, now faces a lack of access to dollars from its oil sales.

“It [the April crackdown] was a security rather than an economic decision. When a security decision is made, one cannot expect proper economic results.”

Economic journalist Farideh Enayeti, who writes for Sazandegi newspaper, also questioned whether such a policy would be helpful in combating corruption and fraud, pointing out that organisations working legally could also end up being tarnished by accusations of nepotism.

'If there is corruption, it is up to judicial authorities to deal with it, rather than Twitter and Facebook pages run by ordinary people'

- Farideh Enayeti, journalist

"Moves like publishing such lists are psychological, and they add to distrust of private companies,” she told MEE.

“Many of these companies that are doing well do not want media to label them in this way. If there is corruption, it is up to judicial authorities to deal with it, rather than Twitter and Facebook pages run by ordinary people.”

The authorities and government are now working to identify and punish those who have broken the law. The finance ministry has also launched a secondary forex market where importers and exporters reach a consensus over the rate of the dollar.

Enayeti told MEE: "When the economy starts to deteriorate, people come under much more pressure and it is clear that they will gradually lose their trust in government.

“We should still wait to see what happens with the Iran-Europe talks for saving the nuclear deal, as a positive outcome could bring stability to the economy."

Middle East Eye propose une couverture et une analyse indépendantes et incomparables du Moyen-Orient, de l’Afrique du Nord et d’autres régions du monde. Pour en savoir plus sur la reprise de ce contenu et les frais qui s’appliquent, veuillez remplir ce formulaire [en anglais]. Pour en savoir plus sur MEE, cliquez ici [en anglais].