Islamic State closes in on Libya’s oil crescent

Members of the Islamic State (IS) have their sights set on gaining full control of an area known as Libya’s oil crescent, according to residents in the Libyan town which has become IS’s latest conquest.

At a meeting with leaders from Harawa, IS militants said they were not interested in the town itself but needed it under their control as part of a planned takeover of the country’s central oil facilities, a senior resident of the town told Middle East Eye. Wary of the strong resistance Harawa had put up against its expansion in the region, IS negotiated an agreement with the tribal elders before entering the town and raising the flag above public buildings on Friday.

“In the negotiations IS said that before Ramadan they would enter the oil crescent,” he said, speaking on condition of anonymity. Although locals had previously warned Libya’s rival governing institutions that the militant group was targeting the area for its oil, this was the first time IS had spoken of their plans, he said.

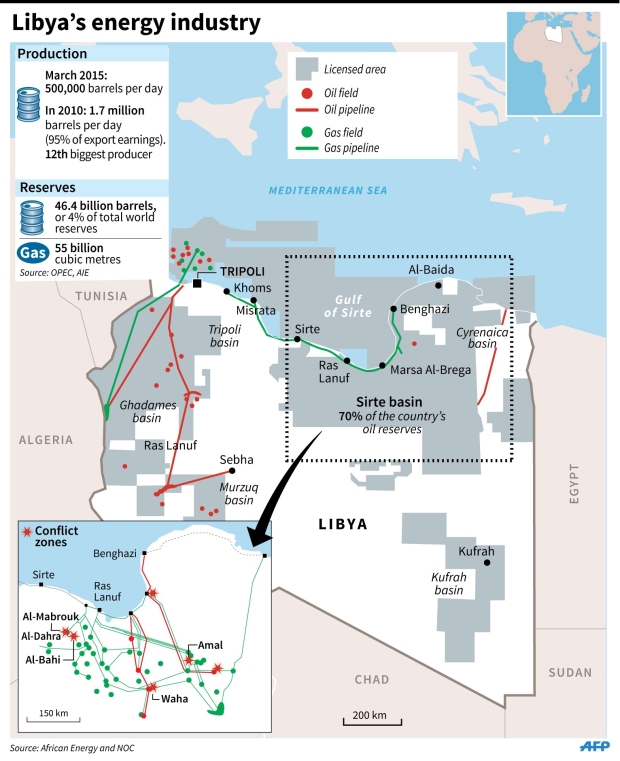

IS already has full control over the desert town of Nufaliya, just 50 kilometres from Libya’s largest oil export terminal of Es-Sidra, and controls much of Muammar Qaddafi’s former hometown of Sirte. Now having taken Harawa - strategically positioned between Sirte and Sidra in the centre of Libya’s coastal highway - it has secured a route to the oil crescent.

The desert region to the south of the oil ports has also been strategically cleared in a series of attacks by IS militants on security personnel and oil fields, where employees have been killed and kidnapped, and vehicles and equipment seized. Such assaults, over a six-month period, forced workers in nearby oil facilities to flee and has left the area vulnerable, according to one former oil worker, Mohamed.“I expect they will try and take Sidra and Ras Lanuf and the oil fields on the west side of the oil crescent,” he predicted. “There are few people left to protect the oil fields apart from local security from isolated towns.”

The oil ports of Sidra and Ras Lanuf are not under the control of either of Libya’s feuding governments. For almost two years they have been controlled by self-appointed federalist leader Ibrahim Jadhran. Then heading the country’s oil protection forces, he gained control of facilities by leading workers in an industrial action that kept four ports closed and cost Libya millions of dollars in lost oil revenue.

These strikes - initially about pay and conditions - became part of a larger federalist movement demanding greater autonomy and a larger portion of the country’s oil wealth for eastern Libya.

Despite attempts by successive Libyan premiers to dislodge him, Jadhran has maintained a powerful presence in the region, including full control over the Sidra and Ras Lanuf oil ports and influence over a third export terminal further east at Zueitina.

When the Tripoli government launched an ultimately unsuccessful bid to take the Sidra facility, Jadhran joined forces with the Libyan Army, operating under the internationally-recognised parliament in the east, to repel the assault. After Tripoli forces withdrew in March, so too did the Libyan Army. Nothing further has been heard of this partnership - one of the many shifting allegiances in the Libyan civil war, where the proverb "the enemy of my enemy is my friend" continues to resonate.

“Jadhran is a mystery even to us. We have not yet understood what he really is, apart from an oil thief,” said Misrata Military Council head Ibrahim Beitemal. “We have attempted to open dialogue with him but he does not like to collaborate because he doesn’t agree with the east or the west.”

He also claimed one of Jadhran’s brothers had joined IS in Libya, something that local people say is common knowledge in the area.

Whether Jadhran has any direct involvement with the militant group remains unclear, although Beitemal claimed that intelligence suggested he had tried to broker a deal with IS. “We have been told that Jadhran proposed some reinforcements to ISIS but on the condition that he kept control of the oil ports and fields, but this was rejected,” he said.

IS continues to destabilise the region targeting forces under the Tripoli government, at checkpoints along the coastal road and on the outskirts of Misrata. In the early hours of Sunday morning, three soldiers were shot dead at a checkpoint on the road between Misrata and Sirte.

Since taking over Harawa, IS has established five regular checkpoints on the coastal highway in a public display of the extent of its control.

Harawa is thought to be the first Libyan town that IS had been forced to negotiate with before raising its flag above public buildings. Local resident Haithem said that despite its willingness to fight IS, the town had received no military support and, after the fall of Sirte had been left with no choice but to negotiate a truce.

Heavily-armed militants entered the town after negotiations were completed, handing back three prisoners from Harawa that were seized during previous clashes, as a “goodwill gesture” intended to encourage the tribal elders to hand over local fighters who killed IS members in two rounds of clashes. Preaching at the town’s main mosque, IS instructed people not to raise the Libyan flag of independence and said that members of the police and army should resign and sign recantations.

Any security and protection would now be provided by the militants themselves, Haithem said.

War planes, reportedly from the Tripoli government, circled above the town after IS fighters entered Harawa but were repelled by anti-aircraft fire from the ground.

Although the black flag now flies above the local council building, Haithem described the situation as an “uneasy truce” explaining that neither side fully trusted the other.

Middle East Eye propose une couverture et une analyse indépendantes et incomparables du Moyen-Orient, de l’Afrique du Nord et d’autres régions du monde. Pour en savoir plus sur la reprise de ce contenu et les frais qui s’appliquent, veuillez remplir ce formulaire [en anglais]. Pour en savoir plus sur MEE, cliquez ici [en anglais].