Islamic State in Libya: The power of propaganda

TRIPOLI - Fears are growing about the radicalisation of young people in Libya after the Islamic State (IS) announced that one of the suicide bombers who led an assault on two of the country’s main oil ports last week was a Tripoli teenager.

After the revelation that the 15-year-old Libyan was one of those who carried out suicide attacks on 4 January, Libyan media reported that the boy had disappeared from his home in Tripoli four months ago, after being radicalised in a mosque in the capital. In a call to his family after he vanished from home, he told them he had joined IS and was in Sirte, according to Libyan news outlet Alwasat.

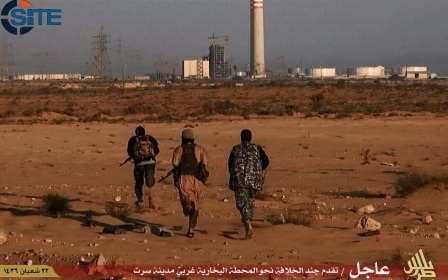

Libya’s struggle with instability and civil conflict in the wake of the 2011 uprising has made the country a fertile ground for IS, which has attracted foreign fighters and garnered some local support. It now has complete control over 300 kilometres of coastal territory, including four towns and a further four villages.

The militant group is spreading its reign of terror beyond its declared territory, with attacks in the past week targeting a police academy at Zliten, 280 kilometres west of Sirte, as well as the oil ports of Sidra and Ras Lanuf. These latest assaults indicate the presence of sleeper cells in other Libyan towns, local people say.

“We have Daesh [the Arabic acronym for IS] in our town, for sure,” said a senior official from al-Khoms - just 115km from Tripoli - who spoke to Middle East Eye on condition of anonymity. “They are small in number, but it’s like a snowball. They are targeting our youth now, and this is how they become strong.”

He said that propaganda DVDs were being surreptitiously distributed among young people.

“I have watched this film and it is like a promotional video designed to brainwash 15- to 25-year-olds. Believe me, if you see it, you can understand why people join Daesh,” he said. “I think they used professional psychologists because they know exactly how to affect the minds of young men.”

The official said IS was preying on vulnerable young people who were religious but poorly educated, adding that some youngsters from Khoms had already left the town and were now believed to be in Sirte.

“I think they went because of promises of money and other benefits. Daesh seems to have a lot of money to recruit people,” he said. “If a young man wants a woman, Daesh promises him three women. If he wants a knife, Daesh will give him an AK47. If he wants to go to Europe, Daesh says no problem, just fight with us for two years and then you can go.”

Several displaced families who had fled from Benghazi, where IS militants are fighting alongside rebel groups and members of al-Qaeda affiliate Ansar al-Sharia against government forces, were behind the DVD distribution, he said.

“Daesh has not yet declared our town is part of its state, but people have to understand what is coming,” the al-Khoms official said. “There are sleeper cells in Tripoli and Misrata, as well as in the western towns of Zawia and Sabratha. In Libya, we cannot stop the spread of Daesh now.”

Similar material glorifying IS ideologies and operations has been circulating in Libya for several years, according to a former official from the town of Nofaliya, which was declared part of IS earlier this year. “Filmed mainly in Iraq and Syria, these films show young men happily leaving on suicide missions or beheading Syrian and Iraqi soldiers,” he said. “They are very high-quality and, along with the extremist preaching in the mosque, inspired many of our sons to join ISIS.”

In Tripoli, the Special Deterrence Force has started to dismantle IS sleeper cells, making a number of arrests. In a recently released hour-long video about IS activity in the capital, seven men captured by the force confessed to being IS members and gave details about their operations in Tripoli during 2015, including attacks on a five-star hotel and diplomatic missions. One of the IS militants said these attacks were designed to gain media attention and further isolate Libya from the outside world.

The youngest captive said he had been trained in an IS camp in Libya where trainees were mainly born in the 1990s and were under 25. It was unusual to see older recruits amongst the many nationalities, which included Tunisians and Europeans, at the training camp, he said.

The men had all previously been in Sirte, the nucleus of IS activity in Libya after the militant group lost control of the eastern town of Derna. Sirte itself has been all but cut off from the outside world after IS shut down telephone and internet networks, enabling it to keep a tight check on information coming out of the town. But former residents who have fled say IS members in the town now run to several thousand, many of whom are foreign militants.

In and around Sirte, a local radio station is being used to spread propaganda amongst residents and passing travellers after militants commandeered broadcasting equipment. The al-Bayan station provides 24-hour coverage of IS operations in countries including Yemen and Russian Caucasus as well as Libya.

Propaganda material is also regularly distributed at checkpoints along the 300km stretch of coastal highway that is under IS control. Driving to the capital from eastern Libya last week, businessman Abdul Hassan said he was shocked by the visible IS presence along the road.

“The town of Harawa was completely deserted. I counted five black ISIS flags, and they have painted their logo on the front of two government buildings,” he said. “I knew they controlled the area, but to see the reality was something unbelievable because I’ve been using that road for 40 years.”

He said he was handed a propaganda leaflet by militants manning one IS checkpoint. “It was all about the family history of IS leader Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi, claiming that his ancestors were related to the Prophet Mohammad. But I don’t think it’s true. It’s like brainwashing, to make more people believe in his authority and join IS,” he said.

Middle East Eye propose une couverture et une analyse indépendantes et incomparables du Moyen-Orient, de l’Afrique du Nord et d’autres régions du monde. Pour en savoir plus sur la reprise de ce contenu et les frais qui s’appliquent, veuillez remplir ce formulaire [en anglais]. Pour en savoir plus sur MEE, cliquez ici [en anglais].