Jamal Khashoggi: The Saudi insider who spoke up for free speech

Editor's note: Jamal Khashoggi has been missing since entering the Saudi consulate in Istanbul on 2 October. His disappearance is the subject of a Turkish murder investigation. Saudi officials have repeatedly denied any involvement in his case, but on Friday, Saudi Arabia said Khashoggi died after a fight broke out inside the consulate.

In the months before Jamal Khashoggi vanished in Istanbul, he told friends that he was homesick.

The journalist's marriage had recently ended after his wife, under pressure from Saudi authorities, had divorced him, and he was living alone in an apartment just outside of Washington.

Khashoggi, by then 59 years old, knew the US capital well enough. In the days when he was still close to members of the Saudi royal court, he had worked as a media adviser to Prince Turki bin Faisal, the former intelligence chief who served as ambassador to the US between 2005 and 2007.

During a visit there two days after Donald Trump had been elected US president in November 2016, Khashoggi told an audience at the Washington Institute for Near Eastern Policy that Saudi Arabia was right to be nervous about the man about to step through the front door of the White House.

I have left my home, my family and my job, and I am raising my voice. To do otherwise would betray those who languish in prison

- Jamal Khashoggi, September 2017

Soon afterwards, he told friends that Saud al-Qahtani, an adviser to Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman (MBS), told him that he had been banned from writing and tweeting. For a year still in Saudi, he wavered uncomfortably. "I am a journalist," he said.

Last September, alarmed by a wave of arrests, he went into exile in suburban northern Virginia, breaking his media silence defiantly that month in the first of his soon-to-be regular columns for the Washington Post newspaper.

"It was painful for me several years ago when several friends were arrested," he wrote. "I said nothing. I didn't want to lose my job or my freedom. I worried about my family.

"I have made a different choice now. I have left my home, my family and my job, and I am raising my voice. To do otherwise would betray those who languish in prison."

In and out of favour

This was only the latest turn for Khashoggi, who had been in and out of Saudi royal favour for decades after his start as a reporter in the complex and shifting world of Saudi media in the 1980s.

He had been fired over editorial choices, sometimes more than once from the same place. Let go by one member of the royal family, he went on to serve as an adviser to another.

But from newsrooms to embassies to royal entourages, the one constant, say friends and colleagues, was that Khashoggi operated from inside the system that he sought to change - and not into a Western-style democracy, but a kingdom that stood against tyranny; he sought to bring more, rather than fewer, voices to the table of governance and was, above all, seeking a place for free speech.

"I want my country to be on the side of history," he told a journalist in 2015. "Saudi Arabia should have a relationship with all sides in the region, particularly powers, groups, that share the same values with us ... I would love to have a democracy in Saudi Arabia, but it is not an issue today. The system is working today in Saudi Arabia."And it was this instinct to work from within, say friends and colleagues, that would prove to be his downfall.

Gregarious and warm as he was, friends and colleagues frequently recall a calmness in the tall Saudi, and a sharp, zen-like way of thinking and speaking, even in the most harried moments and on topics of intense conflict.

"If I didn't know he was a Muslim, I would think he was a monk," said Saad Djebbar, a London-based lawyer who first encountered Khashoggi when they were on opposite sides of a libel lawsuit involving a Saudi publication he worked for at the time. The pair became firm friends.

If I didn't know he was a Muslim, I would think he was a monk

- Saad Djebbar, friend

He wasn't a revolutionary, nor a dissident, and never saw himself as one, even in his year in exile, say friends, but was instead a red-line pushing patriot whose integrity attracted allies with a wide range of politics and beliefs. An adviser to one, an interlocutor to another, he was a man wedged in the middle of worlds, someone who was many things to many people.

Another long-time friend, a Saudi dissident living in London who didn't want to speak on record over fears for his own safety, said it was exactly this candour that so angered the latest iteration of the royal family who preferred an enemy they could vilify.

"Jamal was the opposite. He was very rational. He criticised them in a polite manner, and it was always constructive criticism. This led to hatred. MBS hated him for this," he said.

Said a third friend: "He had a saying - 'Say your words, and go'. And he did."

Finding political Islam in Indiana

Born in 1958, Khashoggi grew up in Medina, the second-holiest city in Islam after Mecca, just before the kingdom's oil boom, which would fuel massive construction projects. Residents are renowned around the region for their extreme politeness, generosity and calmness.

But Khashoggi said it was when living in the midwestern US town of Terre Haute, Indiana, that he was first introduced to political Islam, a topic he would become a leading expert on, while studying business administration at Indiana State University.

"It was after 1980 with the Iranian revolution and the rise of Islamic awareness throughout the world," Khashoggi told the American journalist Peter Bergen in a 2005 interview. "I was still living in Terre Haute at that time, and I [began] to attend Islamic conferences and meetings."

At some point, Khashoggi told friends that he had joined the Muslim Brotherhood. Friends said he had left the group years ago but had kept in touch.

At some point, Khashoggi told friends that he had joined the Muslim Brotherhood. Friends said he had left the group years ago but had kept in touch

"The Muslim Brotherhood within Saudi Arabia was not a conventional thing, more like a school of thought," said Azzam Tamimi, a British Palestinian academic who was Khashoggi’s friend for over 30 years. "He would identify with us. He would link up with us ... it's like being a member of a school of thought more than anything else."

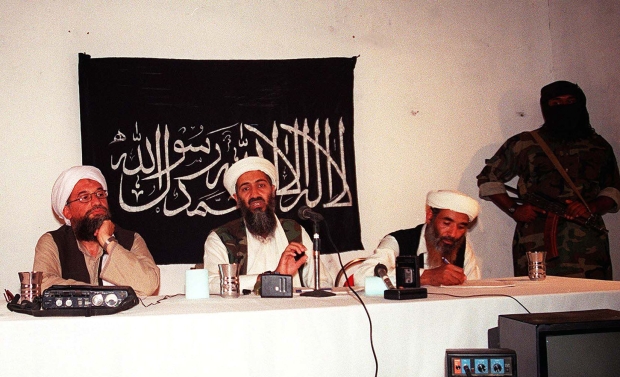

Seven months after he graduated, Khashoggi started working at the Saudi Gazette. Then, as a foreign correspondent for Arabic daily Al-Sharq al-Awsat and English-language Arab News, he became the first journalist from a major Arab news outlet to profile Osama bin Laden in 1987.

At the time and until the mid-1990s when his attentions turned to attacking the West, bin Laden was a hero in Saudi Arabia, a leader of Arabs helping fellow Muslims fight against the Soviets in Afghanistan. Khashoggi had spent some time with bin Laden in Jeddah when they were children, telling Bergen he knew him "slightly".

"We are from the same generation, same background," he said. "Osama was just like many of us who [had] become part of the [Muslim] Brotherhood movement in Saudi Arabia. The only difference which set him apart from me and others, he was more religious. More religious, more literal, more fundamentalist."

After bin Laden"s initial invitation to travel to Afghanistan and write about the Arab fighters, Khashoggi would go on to interview him several times until 1995.

"When I went to Afghanistan [first in 1987] what Osama had in mind and Abdullah Azzam [Al-Qaeda's co-founder] had in mind was to use me somehow to tell about the opportunity waiting for the Arabs in Afghanistan so they could invite more Arabs," he said.

Khashoggi said bin Laden could see that the fighting in Afghanistan would end soon and asked him what would happen to the Arab fighters. "They will go back to their countries, but the flame of jihad should continue elsewhere," bin Laden told Khashoggi. "It will be called al-Qaeda."

Khashoggi said he was surprised - and concerned. "I discussed it with him, and I said, 'But Arab regimes will not like that'."

He would later tell journalists that bin Laden had "gotten in with the wrong crowd," and publicly questioned after 9/11 why 15 Saudis had been involved in the attacks that killed nearly 3,000 people.

"After all, Osama bin Laden's hijacked planes not only attacked New York and Washington, they also attacked Islam as a faith and the values of tolerance and co-existence that it preaches," he wrote.

Criticising Salafism

Working as a foreign correspondent for pan-Arab newspaper Al-Hayat in its heyday, Khashoggi was on the front lines of many of the key events that would shape the region in the 1990s, reporting from Algeria, Lebanon, Bosnia and Sudan.

In 2003, he became editor-in chief of Al-Watan, one of the biggest newspapers in Saudi Arabia calling for reforms at the time, even though it was partially owned by the royal family.

Less than two months into the job, Khashoggi made world headlines when he was forced to resign after the paper published an opinion piece that questioned Salafism and the roots of extremism days after suicide bombing attacks killed 39 people in Riyadh.

"We believe in Al-Watan newspaper, and we believe in reform," he told the BBC. "The newspaper is more important than I am, and I hope it will continue."

Friends say it was the contacts that Khashoggi had formed during his journalism career, particularly with Muslim Brotherhood affiliates, that made him so valuable to the Saudi government.

Tamimi recalls how in 2005 he and Alistair Crooke, a former British diplomat, had brought Hamas and former US and European officials together for the first time in Beirut. Khashoggi was chosen by the Saudi government to attend the talks.

"They needed him more they he needed them," said Tamimi.

Khashoggi would return to journalism, and to Al-Watan, in 2007, but resigned once again in May 2010 after another column that criticised Salafism. A month later, Prince Alwaleed bin Talal appointed him to lead Al-Arab, a new 24-hour media outlet, he was launching.

"We are going to be neutral; we are not going to take sides," he told the New York Times. "We are going to bring in all sides in any conflict because right now we have a conflict in almost every Arab country."

But 11 hours after the channel started in the Bahrain capital of Manama in February 2015, and after putting an opposition leader on the air, it was shut down and never reopened.

He sided with the Arab Spring and the Arab revolution and they didn't like that

- Azzam Tamimi, friend of Jamal Khashoggi

Friends say it was increasingly difficult for Khashoggi to work after the "Arab Spring" uprisings. "They started curtailing their contact with him and probably started limiting his scope after 2011 because he sided with the Arab Spring and the Arab revolution and they didn't like that," said Tamimi.

Another friend, Djebbar, said that sometime in 2016, Khashoggi – who was writing a column for Al-Hayat – attempted to attend a conference in the UAE, but he was turned away at the airport. A top Emirati official had a problem with him, Djebbar said Khashoggi told him, declining to name the official.

"He gave me the impression at the time that the Saudi authorities were under pressure from the Emirati official to stop him from writing," said Djebbar.

Once Qahtani, MBS's adviser, told Khashoggi that he was banned from writing and tweeting after his comments about Trump in 2016, friends said they were increasingly worried about his safety, setting up plans if he were to disappear and urging him to avoid risky situations.

"He left Saudi Arabia because he knew he couldn't take prison," said Basheer Nafi, the Palestinian academic and writer who had known Khashoggi since the 1990s. "They were picking up his friends right and left, and he thought that eventually they would reach him."

But mainly, said Nafi, Khashoggi just wanted to write – and he did.

Responding to the latest wave of arrests in the Washington Post in November 2017, Khashoggi questioned whether bin Salman was more like Russian President Vladimir Putin or Mikhail Gorbachev, the reforming leader of the Soviet Union.

"As of now, I would say Mohammed bin Salman is acting like Putin. He is imposing very selective justice. The crackdown on even the most constructive criticism - the demand for complete loyalty with a significant 'or else' - remains a serious challenge to the crown prince's desire to be seen as a modern, enlightened leader," he wrote.

False sense of security

Yet even as Khashoggi criticised the kingdom – raising questions about the direction of Saudi Arabia's war in Yemen, restrictions on media freedom and women's rights - he said he supported MBS's Vision 2030 project and even complimented the crown prince on his reforms.

The Saudi dissident friend says Ambassador Khaled bin Salman, MBS's brother, offered to set up a media organisation for him. He also told friends Qahtani, the crown prince's adviser, had made a similar offer. "But of course he rejected the offer," the dissident said.

Instead, Khashoggi was launching his own projects, reportedly planning a website which would carry translated reports about Arab economies and starting an advocacy group called Democracy in the Arab World Now. And he was aware, painfully at times, at how Saudi Arabia was changing under MBS. But when he agreed to enter the consulate in Istanbul earlier this month, friends say, he may have had a false sense of security because he had so fluidly moved from inside and outside the royal circle throughout his adult life.

"Jamal's experience on intelligence when he was with Turki bin Faisal made him believe that the current situation was like it has always been," said the dissident. "When he was here in London ... he saw how bin Faisal treated opposition figures here and he thought he would be treated in the same manner."

Bruce Riedel, a former CIA analyst and director of the Brookings Intelligence project who first met Khashoggi when he was a media adviser in the Saudi embassy in London, said it had been slow going, but possible, until a couple of years ago, for someone like Khashoggi to push for change.

We were so expectant. He had been feeling so lonely, but I could see the clouds clearing

- Hatice Cengiz, Khashoggi's fiancee

"The king and the royal family tried to reach a consensus among themselves and then reach out to the clerical establishment and to the business elite. It didn't always happen ... but you could be critical of a decision without fearing for your life," said Riedel. "I think Jamal understood that was changing, but didn't understand how deadly that change was going to be.

"And there is of course the very passionate point that he went into that embassy for love. It's really quite moving."

After a year of homesickness and longing, Hatice Cengiz, Khashoggi's fiancee, who waited outside as he entered the embassy on 2 October, said it was a time of new beginnings: "We were so expectant. He had been feeling so lonely, but I could see the clouds clearing."

In his last Washington Post piece, which was published on Wednesday, Khashoggi remained focused on free speech, which he believed, until the end, would catalyse real change.

"Through the creation of an independent international forum, isolated from the influence of nationalist governments spreading hate through propaganda," he wrote, "ordinary people in the Arab world would be able to address the structural problems their societies face."

Middle East Eye propose une couverture et une analyse indépendantes et incomparables du Moyen-Orient, de l’Afrique du Nord et d’autres régions du monde. Pour en savoir plus sur la reprise de ce contenu et les frais qui s’appliquent, veuillez remplir ce formulaire [en anglais]. Pour en savoir plus sur MEE, cliquez ici [en anglais].