'I would go tomorrow': Inside Kirkuk after the changeover

KIRKUK, Iraq - "We want liquor!" It's an honest assessment from Farideen Yaseen, a father of four, queuing at Ashour Yakoub's salad bar in Kirkuk city centre.

Yakoub has owned the takeaway restaurant and a neighbouring spirits shop in Kirkuk for 20 years.

"Whisky was very popular. People used to buy a mixture of salads to go with their drinks," he said, pointing to the red cabbage, pickled carrots and hummus in the chiller counter.

"No, these are better," chimed a smartly dressed customer, sporting polished black shoes and a trim moustache, and pointing at the pickles.

The mezze on sale are clearly popular – but Kirkuk residents are missing a drink.

After the Kurdish military forces, the peshmerga, pushed back an Islamic State (IS) group advance and took over the city's administration in 2014, alcohol was widely available.

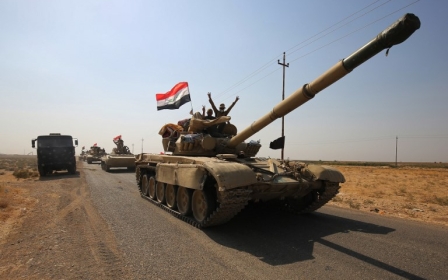

But on 16 October this year, in the wake of Iraqi Kurdistan's controversial independence referendum, the Iraqi army and Shia armed groups of the Popular Mobilisation Forces (PMF) retook the contested, oil-rich city. Since then, there has been hardly a drop of alcohol available for love nor money.

A cluster of stores, including Yakoub's, have plastic emblems for the Turkish beer Efes outside, but their shutters are firmly down.

Beyond the alcohol

Yakoub shut up shop on the day the city changed hands and tried to reopen three days later. But he quickly thought better of it.

"Guards came to tell us to shut the liquor store. They appeared to be army soldiers, but they might have been working on orders of the PMF," he told MEE.

"We are losing out," said Yakoub. "People used to buy food and drink together, and we are suffering now."

In reality, of course, safety has weighed more heavily on residents' minds than the availability of whisky and arak.

I might stay here in my house, or try to move my family to Turkey. If any country gave me asylum, I would go tomorrow.

- Yaseen, regular at Yakoub's salad bar in Kirkuk

"We are upset about the fact there is no liquor," said the customer Yaseen. "But it is not about alcohol, rather the security situation here.

"Up until now, things have been safe, so we will have to see. I might stay here in my house, or try to move my family to Turkey. If any country gave me asylum, I would go tomorrow."

Insecurity and insurgency

Alcohol aside, Kirkuk has undergone significant changes since federal Iraq reasserted its control on 16 October.

On 5 November – a week after MEE spoke with Yakoub's customers - two suicide bombers detonated their explosives in Kirkuk, killing five people and injuring 20 more. No group claimed responsibility for the attack, but Iraqi security forces believe IS cells may try to wage an insurgency after losing 90 percent of the territory they once held in Iraq and Syria.

Conflict analysts say PMF units involved in the Kirkuk assault alongside the Iraqi army include the Badr Organization, Kata'ib Hezbollah, and Asa'ib Ahl al Haq. They believe these Tehran-backed groups will remain operative in Kirkuk and its lucrative oil-rich surrounds, with reports of Iranians given significant roles in local security operations.

"Iran's proxies will capitalise politically and militarily on their role in Kirkuk," according to an analysis by the Institute for the Study of War, a US-based policy research organisation.

Some checkpoints in Kirkuk remain topped with the PMF's white, green and black flags, and the words "Asa'ib Ahl al-Haq" (the league of righteous people) were seen scrawled in graffiti on a wall approaching the city centre.

But there are signs that armed groups may be handing over security duties in Kirkuk to the army. After the double bomb attack on 5 November, Shia cleric Muqtada al-Sadr ordered Saraya al-Salam, a PMF brigade answering to him, to leave the city within 72 hours.

Religious insignias are more apparent in the city than before. Street lamps – from which Kurdish sunburst flags fluttered like bunting – are now naked. Instead, large flags bear representations of the face of Imam Hussein, grandson of the Prophet Muhammad, who is widely revered as a martyr by Shia Muslims.

'Where is your ear?'

Kirkuk, home to around one million people, has long been multi-ethnic, with Arab, Kurdish and Turkmen populations. Until recently, the different ethnicities generally co-existed peacefully.

But Kurdish authorities say 150,000 people have been displaced from Kirkuk and other areas assaulted by federal Iraqi forces since 16 October.

Kurds suffered ridicule at the hands of the Iraqi army and PMF fighters now in charge, according to one Kirkuk resident interviewed by MEE.

"At a checkpoint, guards knew I was Kurdish, so they pulled me over for questioning," said Aram, who gave his first name only.

"They said, 'where is your ear?'" – a derogatory question suggesting stupidity. "I felt very upset, but I couldn"t do anything."

“I feel safer now with the Iraqi army and the Hashd in control," said Alaa Jamal, who runs a fish restaurant in Kirkuk, referring to the PMF by its Arabic name.

Next to Jamal's restaurant stands the shell of the Kurdistan Democratic Party (KDP) Kirkuk office, which was burnt down as federal Iraqi forces retook the city.

"The KDP was not behaving well here, and that's why people burnt this building," said Jamal. "Under the Kurds, we felt discriminated against because we weren't Kurdish. Opening a shop was impossible without a Kurdish sponsor. I felt under pressure, and I did not like their governance."

Political battlefield

Masoud Barzani, leader of the KDP, has tried to frame the takeover of Kirkuk as an Iranian plot. "The operation to take over Kirkuk was led by the Iranians with the knowledge of the US and British officials," he told Newsweek magazine earlier this month.

Barzani, the former president of Iraqi Kurdistan who resigned last Wednesday amid post-referendum turmoil, has blamed the PUK, another major political party in Iraqi Kurdistan, for agreeing to cede authority of Kirkuk to federal Iraq.

In his resignation speech, Barzani accused opponents of a "national betrayal" over Kirkuk, by "co-operating with the PMF against the people of Kurdistan".

The PUK has historically been closer to Baghdad and Iran than the KDP – a point of contention between the two Kurdish parties. Fuad Masum, the present PUK party leader, is also president of Iraq, while the Talabani clan, central to the party’s leadership, has historically been close to Iran.

The KDP also framed the takeover as an "Arabisation" of Kirkuk, inflammatory because it likens the current operation to the Baath Party's mass population displacements of Kurds, Turkmen and Assyrians in the 1970s.

Although some within the PUK have denied a handover of Kirkuk, analysts believe the party played a central role, under Iranian pressure. The party "allowed Baghdad to take large sections of Kirkuk without a fight by negotiating a deal that saw PUK peshmerga simply hand their positions over to Iraqi forces," according to The Soufan Group, a New York-based intelligence firm.

'In my heart'

That may explain why the PUK still appears welcome in Kirkuk. Posters of Jalal Talabani, the president of Iraq from 2005 to 2014 and who died on 3 October, line the city streets. On one roundabout, his face flanked three of four exits. Black banners carrying mourning messages to "Mam," meaning uncle, Jalal remained scattered over the city.

"The PUK is still supported here," said Ahmed Adeeb, whom MEE interviewed alongside Alaa Jamal, the fish-restaurant manager. "The Iraqi army and the Hashd are okay with them, but not with the KDP."

Kirkuk residents feel it is too early to judge how life will continue in the city. Even if it does so without a drink to ease things along, Ashour Yakoub will stay.

"Some people fled Kirkuk, but if you run away the people who are looking for you will come to get you anyway."

His customers know they can no longer buy a drink, but they want to keep supporting the business. Their loyalty to the store seems to reflect a wider faith to a diverse Kirkuk.

"I will keep coming here," said the man in the shiny shoes, who declined to give his name. "This place is in my heart."

Middle East Eye propose une couverture et une analyse indépendantes et incomparables du Moyen-Orient, de l’Afrique du Nord et d’autres régions du monde. Pour en savoir plus sur la reprise de ce contenu et les frais qui s’appliquent, veuillez remplir ce formulaire [en anglais]. Pour en savoir plus sur MEE, cliquez ici [en anglais].