Beach graveyard: Libyan town seeks dignity for thousands who died on its shores

ZUWARA, Libya - Sadiq Jiash can barely hide his emotion as he sketches out his plans for the first "real" resting place for hundreds, perhaps thousands, of victims of Libya's people-smuggling industry.

"It will be evenly spaced, with bodies buried in groups of 100 which will be numbered," he says, "There will be paths, a surrounding wall, and there will also be a guard. It will be a real cemetery, you know?"

We cannot leave them there. The sea will eventually bring the corpses to the surface

- Sadiq Jiash

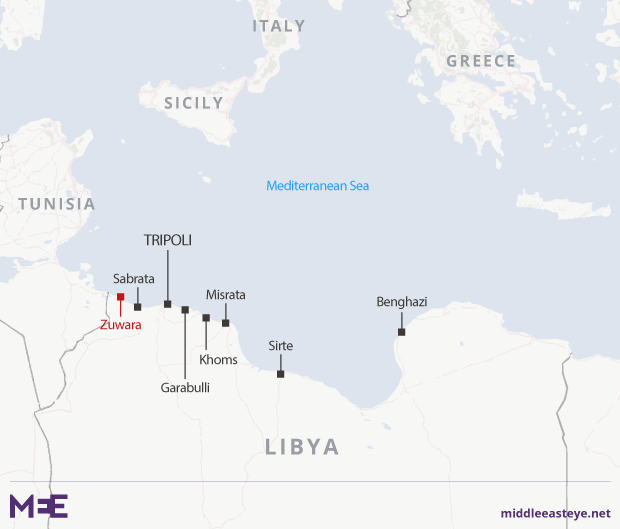

This is Zuwara, 100km to the west of Tripoli, where discovering the dead on the shoreline was once a daily reality, and where an emergency committee is trying to create a final resting place for the 2,000 already interred in a makeshift mass grave over the last three years.

Jiash admits his volunteers have a difficult, tragic and horrifying task ahead. But it must be done, and fast.

The original site near the beach is waterlogged, and regularly gives up its contents when the weather turns. Very few people were buried in shrouds, let alone coffins. Wild, hungry dogs prowl the site.

"Everything started in 2014, when we found more than 100 bodies on our beaches," says Jiash, as he explains how the temporary site began.

"At first we wanted to bury them in the local cemetery but many people said some of the dead might not be Muslim. The locals said they could not mix."

Burying them on the outskirts of the city was also opposed. Arable land is scarce, and locals do not want their gardens turned into graves. "Who could possibly blame them?"

"We cannot leave them there," says Jiash. "It is very close to the coast and the sea will eventually bring the corpses to the surface.

"It gets waterlogged when it rains. The dogs are attracted by the smell."

But with little money, few resources and the logistical nightmare of dealing with three governments - two in Tripoli and one in Tobruk - this is but one emergency the committee must confront.

Near the temporary graveyard is an abandoned petrochemical plant which, the emergency committee says, leaks mercury, ethylene and other toxic substances into the ground and sea. "It's a massive health threat for all of us but we have no means to tackle it," says Jaish.

In October, thousands of Sub-Saharan migrants arrived in the city fleeing clashes in nearby Sabratha.

Zuwara's mayor, Hafed Bensasi, admits his task is overwhelming.

"We have to attend those and many others because they are human beings, but in doing so we are also putting in danger our own survival," he said, noting that half his budget goes on security.

The town is Libya's only coastal Amazigh enclave, and is surrounded by an arc of Arab villages where loyalists to the dead leader Muammar Gaddafi are still dominant.

The fallout from Sabratha, a former stronghold of the Islamic State group and Libya's largest human-trafficking hub, must also be contained.

"We have no means. We can only put out fires," says Bensasi. "We can only plug holes in a boat that does not stop sinking."

In spite of this, Zuwara has gained a grip on the biggest cause of its troubles: it is no longer a focal point for human-trafficking, its leaders say.

A "special brigade" of volunteers, created by the emergency committee after 200 people washed up on the beach in August 2015, has stymied the gangs of people-smugglers.

Today, only Libyans depart from Zuwara, and in their own fishing boats.

Jonah, a 26-year-old Nigerian and one of hundreds of migrants in Zuwara's martyrs' square, is looking for work, not a boat to Europe. The town is the safest place for him at the moment in the turmoil that is Libya.

"You see that guy over there listening to music on his mobile phone? You would never do such a thing in Tripoli; someone would give you a beating and take it from you straight away."

But he knows he will have to move elsewhere when he gathers the amount to buy a passage on a raft.

And the town cannot stop the industry in other areas, such as Sabratha, and must continue to deal with appalling results - the bodies continue to pile up on its beaches.

According to the UN, more than 140,000 people have arrived in Europe from Libya so far this year. Many others do not make it, and every body retrieved in Zuwara is processed by the local branch of the Red Crescent.

Ibrahim Atushi, the head of the NGO's Zuwara branch, says DNA tests are taken, pictures are taken for their database and interviews are also conducted with migrants to gather "as much information as possible" to identify those who have died.

While Atushi praises collaboration with Zuwara's emergency committee, he complains about the "lack of support from outside Zuwara".

Doctors Without Borders and the International Organisation for Migration have supported them with body bags and some basic equipment, he says, but he insists that they rely mainly on volunteers to handle the crisis.

In the last four days, Jiash and his team have buried 80 more people in the makeshift graveyard.

A field of tombstones

A drive out to the site takes 30 minutes. The area around it resembles an orchard, but the only things that grow are "tombstones" for the dead - breeze blocks planted every time a body, or multiple bodies, are buried.

"Every now and then we've been forced to dig mass graves so the bricks won't give you an idea of the real amount of people buried here," says Jiash.

"There are 43 on our left and 21 on the nearby parcel; 19 women a bit further; 10 children buried in a row..." he says, sticking to a map which, very likely, only now exists in his mind.

We've been forced to dig mass graves so the bricks won't give you an idea of the real amount of people buried here

- Sadiq Jiash

He points to the area nearby which will soon become the permanent, huge, 18-hectare site, and admits to the terrible ultimatum the committee had to give to get the money needed.

"We left several bodies on the beach for four days until the local authorities agreed to our demands," he says.

He understands the myriad problems Zuwara faces, but giving the thousands of people their dignity in death, "will be money well spent".

Middle East Eye propose une couverture et une analyse indépendantes et incomparables du Moyen-Orient, de l’Afrique du Nord et d’autres régions du monde. Pour en savoir plus sur la reprise de ce contenu et les frais qui s’appliquent, veuillez remplir ce formulaire [en anglais]. Pour en savoir plus sur MEE, cliquez ici [en anglais].