Manchester attack: Government 'barking up wrong tree' with Prevent

Critics of the British government's Prevent programme have accused it of "barking up the wrong tree" after the home secretary on Wednesday reiterated a commitment to bolstering the counter-extremism strategy following the suicide bombing in Manchester.

The government has faced criticism from parliamentary committees, human rights organisations and campaign groups over concerns that Prevent, part of the UK's broader counter-terrorism strategy, is discriminatory against Muslims and potentially undermines free speech and civil liberties.

But Amber Rudd, speaking on BBC radio on Wednesday, said that she did not accept criticism of Prevent, describing it as providing a "system of support" for communties.

She said the ruling Conservative Party planned to go ahead with an "uplift" for Prevent, including more funding, if the party is re-elected in general elections on 8 June.

"There is an industry out there that doesn't like Prevent but I can tell you that 150 people were stopped because of Prevent activity from travelling to Syria last year, 50 of whom were children," she said.

Opposition parties have called for Prevent to be reviewed or replaced with an alternative scheme.

The government has also struggled to introduce a new counter-extremism strategy, announced as part of its legislative programme in both 2015 and 2016 because of its failure to settle on a legally satisfactory definition of extremism.

Rudd said the government was working with 142 community organisations through Prevent to "stop young people being radicalised".

"We will be going ahead with an uplift in Prevent and when we do that we will also be making sure that it also has an even more effective outcome in communities ... to keep us all safe."

Prevent was introduced by Tony Blair's Labour government and rolled out widely in the aftermath of the 2005 London bombings.

The strategy was revised by the subsequent Conservative-led coalition government, which in 2015 introduced the Prevent Duty, a statutory duty for public sector workers including teachers and doctors to "have due regard to the need to prevent people from being drawn into terrorism".

The strategy has been opposed by the National Union of Teachers, the National Union of Students and many university staff amid concerns that requirements for educational institutions to enforce the Prevent Duty undermines free speech.

Last month, MEE reported on how university staff were being advised to "risk-assess and manage" Palestinian activism on campus.

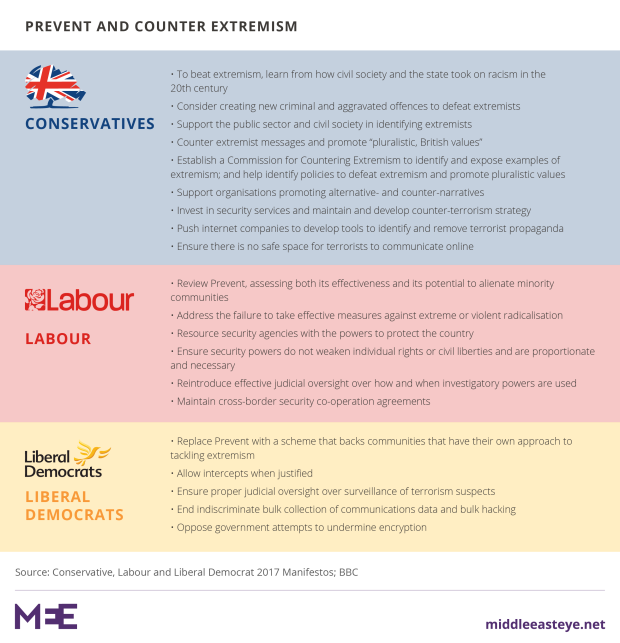

The Conservative Party's manifesto includes pledges to "support the public sector and civil society in identifying extremists" and to establish a commission for countering extremism to "help identify policies to defeat extremism and promote pluralistic values".

The opposition Labour Party has called for a review of Prevent, addressing both its effectiveness and potential to alienate minority communities.

Andy Burnham, a former Labour shadow home secretary who is now the mayor of Greater Manchester, said on Wednesday there was a danger of it casting a cloud of suspicion over a whole community and potentially damaging relations with police, drawing a comparison with the situation in Northern Ireland during the Troubles from the 1960s to the 1990s.The Liberal Democrat Party in its manifesto has called for Prevent to be replaced with "a scheme that backs communities that have their own approach to tackling extremism".

'Barking up the wrong tree'

Rizwaan Sabir, an acadmic specialising in counterterrorism, told Middle East Eye that Prevent was "barking up the wrong tree" by attempting to tackle ideology and ideas rather than the specific security threats and risked creating conditions in which political violence was more likely.

"Prevent has now been operational since 2006 and the question arises why are we still stood here in 2017 11 years later talking about ratcheting up a programme that has no community support, that is distrusted, that is considered to be toxic by many many law enforcement officers, officials and civil servants," said Sabir.

He said that Prevent had also compromised the police's and intelligence services' abilities to identify genuine security threats and gain communities' trust.

"In order to stop political violence you need people to be so trusting of law enforcement agencies and the state that they feel comfortable coming forward to report people. But they cannot do that if they are constantly under a cloud of suspicion which is what Prevent does," he said.

Abed Choudary, of the Islamic Human Rights Commission, told MEE: "The reality is that the government has no idea about how to tackle extremism. This is seen in the fact that that they cannot define or identify what extremism is.

"Prevent allows them to be seen to be acting tough on extremism. In reality, all they are doing is criminalising a community and giving themselves sweeping, draconian powers over the British public as a whole. In the meantime, the issue of how to tackle extremism remains unanswered."

Despite human rights concerns surrounding Prevent, the UK is exporting counter-extremism experience, with the head of Europol, the European Union's law enforcement agency, recently describing the strategy as a "best practice model" for countering radicalisation.

MEE this week also reported that a Prevent strategist had been appointed by a United Nations agency to develop counter-extremism programmes in Central Asia.

Middle East Eye propose une couverture et une analyse indépendantes et incomparables du Moyen-Orient, de l’Afrique du Nord et d’autres régions du monde. Pour en savoir plus sur la reprise de ce contenu et les frais qui s’appliquent, veuillez remplir ce formulaire [en anglais]. Pour en savoir plus sur MEE, cliquez ici [en anglais].