In a Middle East racked by turmoil Iranians have fallen in love with stability

Saeed Leylaz points to the small coffee table in front of the sofas where we are sitting in his living-room. “Imagine another table of the same size and put the two together. They just about cover the area of the cell where I was held,” he says with a rueful smile.

I make a mental calculation. His coffee table is about one and a quarter metres square. Double that in your head and you cannot help wincing at what it must have meant to be locked up in the resulting space for a few hours, let alone the four months that Leylaz spent in solitary confinement in Tehran’s Evin prison. He spent another eight months with other detainees.

They were among dozens of intellectuals, journalists, economists, activists and former government officials who were rounded up after protesters took to the streets against Mahmoud Ahmedinejad’s re-election as president in 2009. Leylaz is an economic journalist who founded and edited the newspaper Sarmayeh. It was closed and he was sentenced to 15 years in prison after being convicted of working to overthrow the government and keeping contact with foreigners. The sentence was twice reduced and he eventually came out after serving a year.

He is banned from appearing on Iranian TV and has had his passport withdrawn, but it is a sign of considerable courage that he is willing to meet a foreign journalist after all he has been through.

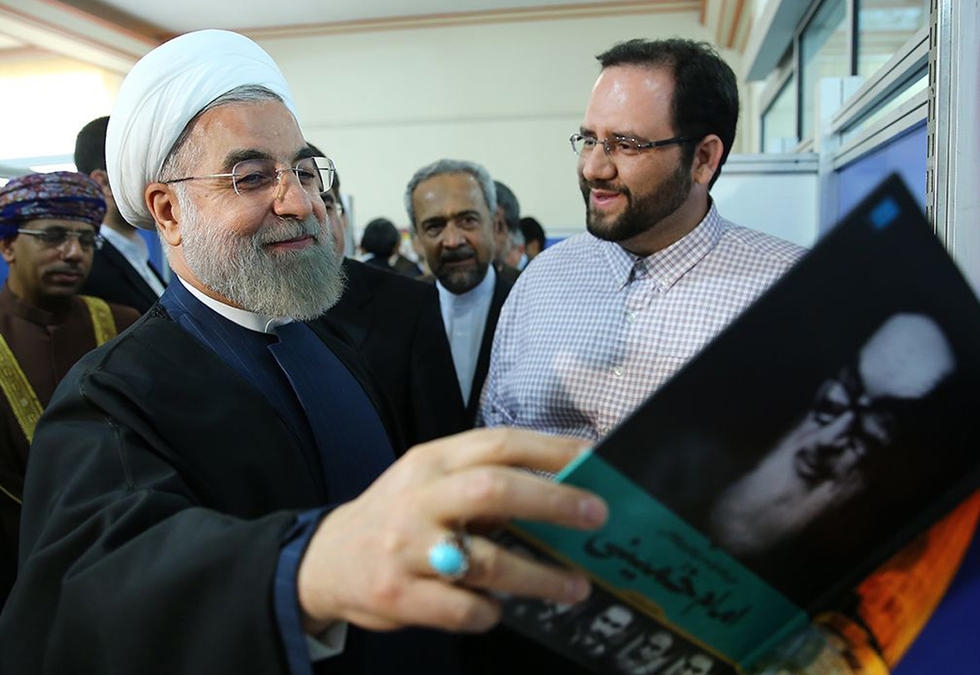

It is also a sign of the liberalisation that has come about since Hassan Rouhani succeeded Mahmoud Ahmedinejad as Iran’s president in 2013. Though the TV channels ignore Leylaz, he is regularly interviewed by Iran’s print media.

Many Iranians would have liked Rouhani to make deeper reforms in the two years he has already spent in power, including fulfilling his earlier promises to release Mir Hossein Mousavi and Mehdi Karroubi, two candidates from the 2009 presidential election who are still under house arrest, as is Mousavi’s wife Zahra Rahnavard.

“Rouhani tries to be freedom-minded and democracy-oriented, but he’s well aware of the nature of the system,” says Davoud Hermidas-Bavand, the Tehran spokesperson for the National Front of Iran.

The National Front is an old secular party, once headed by Mohamed Mosaddegh, one of the great icons of Iranian independence. He was democratically elected as Prime Minister in 1951, only to be overthrown by a British-organised coup after he tried to nationalise the Anglo-Iranian Oil Company.

In spite of Bavand’s critical views and the fact that his party is officially banned, he too can receive foreign and Iranian journalists without reprisals. He calls Iran’s complex political system with its regularly contested elections, while overriding power remains in the hands of clerics, as “open and secret”.

“Expectations were high and people wanted more,” Bavand says of Rouhani’s election, “but he’s concentrated all his energy on getting a nuclear deal. The opposition is trying further to restrict the political atmosphere in advance of a deal, so Rouhani has not taken any steps. He’s very conservative.”

Bavand describes the opposition as the Revolutionary Guard Corps, the judiciary and “some institutions around the Supreme Leader”. In February the judiciary issued a ruling which prohibited the media from quoting or even mentioning Mohammad Khatami, the president who led a reformist government from 1997 to 2005.

The word “reformist’ has gone out of favour since hardliners refer to them as “seditionists”, and claim the 2009 street protests that supported the reformers were orchestrated by Western intelligence agencies. If a nuclear deal is signed, Bavand believes Rouhani’s hand will be strengthened, as will that of those who used to be called reformists when parliamentary elections take place next February.

“The first impact of a deal will be psychological, the second economic and the third will be to allow Rouhani to focus more on the domestic situation,” he says. “If the Majlis elections are free, the hardliners will lose their position.”

A similar view is taken by Ahmed Gholami, chief editor of Sharq, a newspaper that has been banned three times since it was launched towards the end of Khatami’s administration in 2004. Gholami himself has been arrested more than once. He describes his paper as “a kind of opposition paper that criticises on domestic issues within the framework of the Islamic state.”

Iran’s foreign policy and its stance on the nuclear negotiations are taboos, which cannot be touched, as are several domestic subjects, including any analysis of the Supreme Leader’s decisions or his health, the requirement for women to wear hijab, and any criticism of the life-styles or wealth of top figures in society.

“The essentials haven’t changed since Rouhani replaced Ahmedinejad, and freedom hasn’t been extended. But the atmosphere is more logical and rational,” Gholami says.

“Once there is a deal, the hardliners will still criticise the government, especially by putting pressure on over the economy. We know the impact of lifting sanctions will take years and they will keep asking why the economy is still in a bad way," he says.

There is a theory among some Iranian analysts that the Rouhani government will compensate for Iran’s opening to the world after a deal is agreed by toughening up internally so as to resist any threats to the system. Gholami rejects that.

“If there’s less tension internationally, there’ll be more stability internally. People want to undermine the taboos quickly. The state has shown it will not clamp down on social pressures. Now they’re beginning to understand that because of the power of social media they need to manage outcomes rather than control inputs,” he says.

While the debate over the likely effect of Iran’s re-engagement with the West continues, perhaps the most remarkable aspect of Iran’s current political discourse is the emphasis on resisting extremes and broadening the country’s centre ground. One factor is the lessons that reformists and conservatives have drawn from the 2009 crisis when protesters clashed with police and revolutionary militias in central Tehran for several days. In a way Iran’s brief upheaval was a Middle Eastern precursor of the Arab spring of 2011. Yet unlike the Arab spring it did not lead to a dictatorial counter-revolution like in Egypt or a civil war like in Libya and Syria. The other factor is the rise and spread of the Islamic State group with its brutal violence.

The turmoil and bloodshed that Iranians see on their TV screens in Iraq, Syria and now Yemen have given them a stronger sense of the benefits they enjoy in their country. This acts as a counter-balance to their complaints about economic, political and other problems.

“Islamic State has helped Iran in a way. It’s shown people here that Iran has stability and freedom of movement,” said one analyst who wished to remain anonymous.

“People now think twice about taking action to change the system because they know change might result in disaster,” said Abbas, a local blogger.

“They see what’s happening in Iraq, Afghanistan and Syria. It’s not like being in the UK where you read about it in the newspapers. Here you really feel it because it’s close."

Hossein Kanani Moghaddam is a former commander of the Revolutionary Guard Corps who founded the Green Party which has five Majlis members. He describes it as a centrist party “between the fundamentalists and reformists”. The 2009 street protests would not have happened if Iran had strong political parties, he argues.

“Rouhani’s election has opened up the democratic atmosphere to make stronger parties possible. It was the fanaticism of the hardliners and the reformists which prevented the 2009 crisis being resolved peacefully,” he says.

Saeed Leylaz, the economic journalist who was sentenced to 15 years in prison, is a convert to Iran’s new discourse of centrism. Asked what the lessons of 2009 were, he replies: “We realise that if we want to emphasise our own points of view over those of our competitors within this system, the result will be another Syria. This is a great Islamic revolution and we have to sit round the table and try to solve problems step by step."

“Rouhani has been able to make two big changes: relations with the United States and economic growth,” he adds.

“This is a result of our gathering together on the centre ground. Rouhani and Khamenei share the same position on the nuclear talks and the country’s exit from economic difficulties. We and Turkey are the only stable and quiet countries in the region.”

Iran has a long history of absorbing and taming militancy from Tamberlaine to Genghis Khan, he claims. He remembers an article which he wrote a decade ago, likening the Islamic Republic of Iran to a factory. Radicals go in as raw material and the product which emerges are “Westernised gentlemen”.

“This country, this civilisation, is alive. It is thinking,” he goes on in a burst of enthusiasm.

He concludes with an astonishing tribute to centrism in the name of stability: “I prefer to have a strong and powerful Revolutionary Guard Corps rather than a weak one, even though they have done bad things to me.”

Middle East Eye propose une couverture et une analyse indépendantes et incomparables du Moyen-Orient, de l’Afrique du Nord et d’autres régions du monde. Pour en savoir plus sur la reprise de ce contenu et les frais qui s’appliquent, veuillez remplir ce formulaire [en anglais]. Pour en savoir plus sur MEE, cliquez ici [en anglais].