The military: Sisi's real political support base

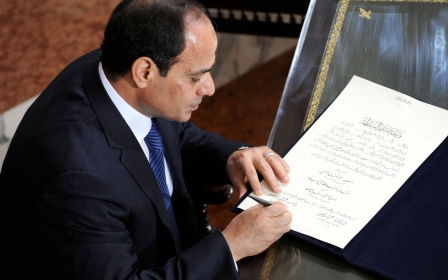

After a shockingly low turnout for Egypt’s first round of parliamentary elections, observers say one of President Abdel Fatah al-Sisi’s top priorities is to legitimise his government.

In a series of visits to influential Western European countries, most notably Germany and the UK, Sisi has sought to actively engage with the the global community in an effort to establish his power and normalise relations with international powers.

With the first phase of the elections bringing a political faction strongly backed by Sisi into parliament, analysts expect the second phase of the polls scheduled for November to bring similar results.

Even with a supportive parliament, however, experts believe Sisi plans to consolidate his political base through the military.

Parliament with no power

Electoral observers have already noted the elections had instances of vote-buying, reported Al-Monitor.

Furthermore, the three electoral coalitions permitted to run in the first phase of the polls - The Call of Egypt, For the Love of Egypt and Independent National Re-Awakening Bloc - have generally supported Sisi. These coalitions are headed by several former intelligence and military leaders, reported Al-Ahram Online on 7 October.

“The parliamentary coalition is led by a former intelligence officer, while the rest of the list includes many ex-military and ex-intelligence men,” said Omar Ashour, senior lecturer in Middle East politics and security studies at the University of Exeter.

For the Love of Egypt is led by former intelligence officer Sameh Seif Al-Yazal, who also ran the state-owned Al-Gomhouria newspaper's Centre for Political and Strategic Studies.

At the same time, Sisi passed a new election law in August that dramatically limits the influence of Egypt’s political parties by alloting 80 percent of parliamentary seats to individuals.

According to Mohamed Elmasry, an assistant professor at the University of North Alabama’s department of communications, the new election law is a return to legislation used by former president Hosni Mubarak to help him consolidate power in the 1980s and 1990s by privileging wealthy elites with ties to the Egyptian establishment.

Unlike Mubarak, however, Sisi is unlikely to rely exclusively a compliant parliament to back him. With potential fractures within the establishment possibly affecting his rule, Sisi has indicated in public statements that he wants to amend the constitution to reduce the parliament’s power, wrote Elmasry on 20 October.

According to Egyptian security expert and former military general Abdel Hamid Omran, “Unlike in democratic countries where a government’s support base comes from the electorate, non-democratic regimes need – apart from military power – an alternative base of support.”

“This support base usually includes individuals whose financial interests are linked to the government such as people in the media and film industries as well as the many corrupt and influential individuals,” Omarn told MEE.

The military as a support base

While Sisi will continue to establish a parliament that provides his government with a level of credibility, analysts say the military and its various bodies are the real powerful institutions that provide Sisi with the power and support he needs.

“The whole country has always been militarised, but what has changed significantly is that the most powerful economic and political player has become the Supreme Council of Armed Forces (SCAF) – removing two presidents (Mubarak and Morsi) and appointing another (Sisi) - and its brains or think tank is the military intelligence,” added Ashour.

Until the 2011 revolution, Egypt had been ruled for more than 60 years by a military presidency. Presidents Gamal Abdel Nasser, Anwar al-Sadat and Hosni Mubarak had all been military leaders before running the country.

It was only in 2012, with the election of the Muslim Brotherhood linked Mohamed Morsi to power, that Egypt was run by a civic government.

Many observers have therefore drawn close links between the return of a military government with Sisi - a former army general - coming to power and the government of Mubarak which was supported by a political class composed of the National Democratic Party (NDP) and the party's affiliated business elite.

“While the military and the security forces more generally are the bedrock of the Egyptian regime, the NDP elites are also part of the regime coalition and despite their differences with Sisi, they are still broadly supportive of the government,” said Shadi Hamid, senior fellow at the Brookings Institution and author of author of Temptations of Power.

But according to Ashour there is a stark difference between the government of Mubarak and that of Sisi.

“Sisi lacks the support of a class like that of the NDP which under Mubarak, won a significant percentage of votes, even if the polls were rigged,” explained Ashour.

“Instead Sisi’s main support is through guns and the army’s institutions. His support base comes form his allies within (SCAF) and the military intelligence which dominates other – previously more powerful - institutions such as the general intelligence.”

While the military has always been powerful in Egypt even during the interim period between the 2011 uprisings and the military coup on 3 July 2013, its intelligence unit was relatively marginal in political affairs.

This has changed since Sisi came to power however, with the military intelligence becoming a leading power within the country and a main support base for the president.

“Under Mubarak the military intelligence’s role was marginal. Its role was mainly to spy on military officers making sure they stayed in line. Every now and then the military intelligence might have tired to push its boundaries a little, but it would be pushed back by the general intelligence or state security investigations unit,” said Ashour.

“One indicator of this change is what happens in political prisons. The most authoritative figure used to be a state security officer… now however the state security officer is topped by a military security officer,” he added.

Middle East Eye propose une couverture et une analyse indépendantes et incomparables du Moyen-Orient, de l’Afrique du Nord et d’autres régions du monde. Pour en savoir plus sur la reprise de ce contenu et les frais qui s’appliquent, veuillez remplir ce formulaire [en anglais]. Pour en savoir plus sur MEE, cliquez ici [en anglais].