Peshmerga push towards Mosul with eyes on a greater Kurdistan

KHAZER, Nineveh, Iraq - The sun has risen in the morning sky and the moon has yet to fade away. The column of armoured vehicles and white pick-up trucks stretches as far as the eye can see, towards a hill clouded with dust and morning fog.

Perched on a peak, nameless silhouettes watch from behind sandbags as they prepare to send rockets towards enemy lines.

The red, white and green flags of Iraq's Kurdish region flap in the wind atop the rolling combat vehicles. Then the rhythmic hum of their engines is drowned out by the staccato scream of machinegun fire, the thud of mortar bombs and the roar of coalition jets across the sky.

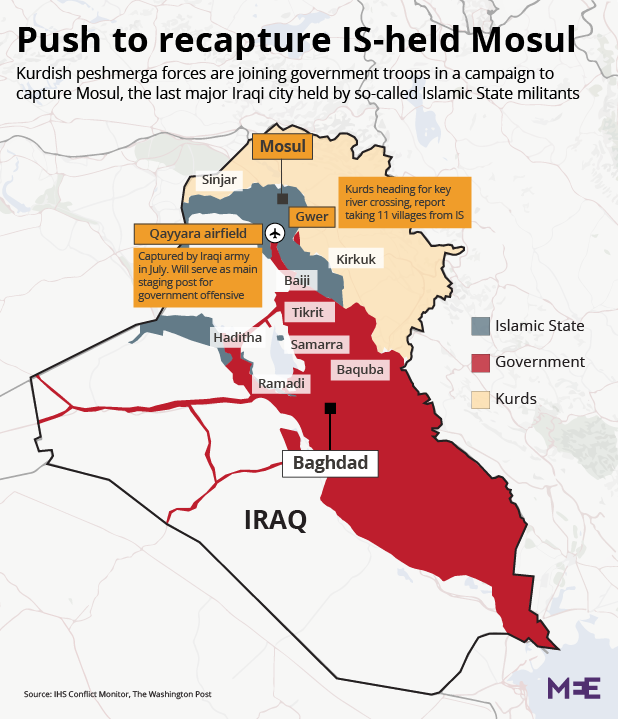

This is the start of the second phase of the Peshmerga's offensive from Khazer to retake territories east of Mosul, the Islamic State (IS) group’s de facto capital in Iraq and the largest city under its control.

It is an operation that the Kurdish forces hope will pave the way to lay siege to the city in cooperation with the Iraqi army and the US-led coalition.

Kurdish authorities say they have taken 11 villages from IS, pushing farther into the group's territory and closing on Qaraqosh in Nineveh province, a Christian stronghold with a pre-war population of 75,000.

“This successful operation will tighten the grip around IS's stronghold Mosul,” Masrour Barzani, chancellor of the Kurdistan Region Security Council, said in a statement.

On day three – Tuesday - clashes were ongoing. Several Peshmerga were wounded by IEDs, while IS fighters launched a series of suicide and car-bomb attacks.

While the Kurds are often eager to say they fight the world’s enemy for the sake of humanity, they do not shy away from talking about their other goal: gaining territory for a greater Kurdistan.

By seizing territory from IS, the Peshmerga establish control over “disputed territories” - areas claimed by the autonomous Kurdish region of Iraq and by the central government in Baghdad.

General Hama Rashid Rostam told Middle East Eye that ground seized by his men is rightfully Kurdish.

“We are fighting IS, but at the same time we have ambitions for Kurdistan, the Kurds as a nation and a people like everybody else,” he said in the freshly captured village of Qarqasha.

"We are ambitious. It’s our right and we are going to get it.”

Home to not only Kurds but also minorities including Turkmen, Assyrian and Chaldean Christians, Yazidis, Kakais and Shabaks, the disputed territories across the Nineveh Plain – where the Peshmegra offensive is taking place - were “Arabised” by consecutive Iraqi governments that expelled hundreds of thousands of local inhabitants from their homes to settle ethnic Arabs.

The Kurdish population says they have faced systematic persecutions, including large-scale massacres during the reign of Saddam Hussein.

Arif Tayfur, the commander of the Khazer sector and a senior KDP official - the political party of the Kurdish president Massoud Barzani - told MEE that Kurds had had every intention of keeping what has historically been theirs.

“The areas we are capturing now, we say it belongs to the Kurdistan region. But they (Baghdad) say it belongs to Iraq. Well, we will not abandon these territories,” he said.

“We sacrificed our blood for our land,” he added, referring to 14 Peshmerga fighters who had died in the offensive so far. “These areas all belong to Kurdistan, but Arabs are living there. We will not give them back."

The rhetoric is sharp, but it is also supported by Iraqi law.

Article 140 of the country's constitution deals with “disputed territories”, and outlines steps that should be taken in order to resolve the territorial arm-wrestling. They include negotiations between Baghdad and Kurdish officials and referendums “to determine the will of the citizens”.

Through negotiations, Kurdish authorities may try to maintain their grip on the areas they seize, or use them as bargaining chips with Baghdad to gain preferred areas such as oil-rich Kirkuk, according to Renad Mansour, a fellow at the Carnegie Middle East Centre.

“In Nineveh Province, they will be able to say: ‘OK, we will give it back, but what do we get in return?’ So they are viewing it as an opportunity as well,” Mansour said.

“But of course, there are certain areas, cities and villages, that they won’t give up or that it would be hard for them to give it up, like parts of Nineveh and Kirkuk.

“The reason they want a referendum is so they can say it’s not an occupation, it’s the will of the people,” Mansour said, adding that after decades of Arabisation campaigns by previous Iraqi governments, “there are definitely concerns that you would have a 'Kurdification'.

“I don’t see them having any sort of aggressive policies of Kurdification, like explicit ones, but again the fears are that there might be more implicit ways of favouring Kurds over others,” he said.

Since the fall of Saddam, Kurdish authorities have relied on “intimidation, threats, and arbitrary arrests and detentions” to secure support of minority communities for their agenda regarding the disputed territories, according to a Human Rights Watch report published in November 2009.

The report said that Kurdish leaders had sometimes pressed minorities living in Nineveh to identify as Kurds.

“The victims of Saddam Hussein’s Arabisation campaign deserve to be able to return to, and rebuild, their historic communities," the report said.

"But the issue of redress for past wrongs should be separate from the current struggle for political control over the disputed territories, and does not justify exclusive control of the region by one ethnic group."

Indeed, it is something with which commander Tayfur agrees. Local minorities should be allowed to choose their loyalties: “If they decide to belong to Baghdad, we would immediately pull back."

Inside Qarqasha, gun shots and mortar explosions could still be heard late in the afternoon.

Resting next to stormed houses, Peshmerga fighters smoked cigarettes and napped, taking cover from enemy snipers.

Behind them, dozens of yellow and orange excavators were already carving out new trenches, coincidentally defining the new borders of their growing region.

“We have a right to fight for a greater Kurdistan,” General Rostam said.

This article is available in French on Middle East Eye French edition.

Middle East Eye propose une couverture et une analyse indépendantes et incomparables du Moyen-Orient, de l’Afrique du Nord et d’autres régions du monde. Pour en savoir plus sur la reprise de ce contenu et les frais qui s’appliquent, veuillez remplir ce formulaire [en anglais]. Pour en savoir plus sur MEE, cliquez ici [en anglais].