Britain's forgotten army of Muslims fighting in WWI

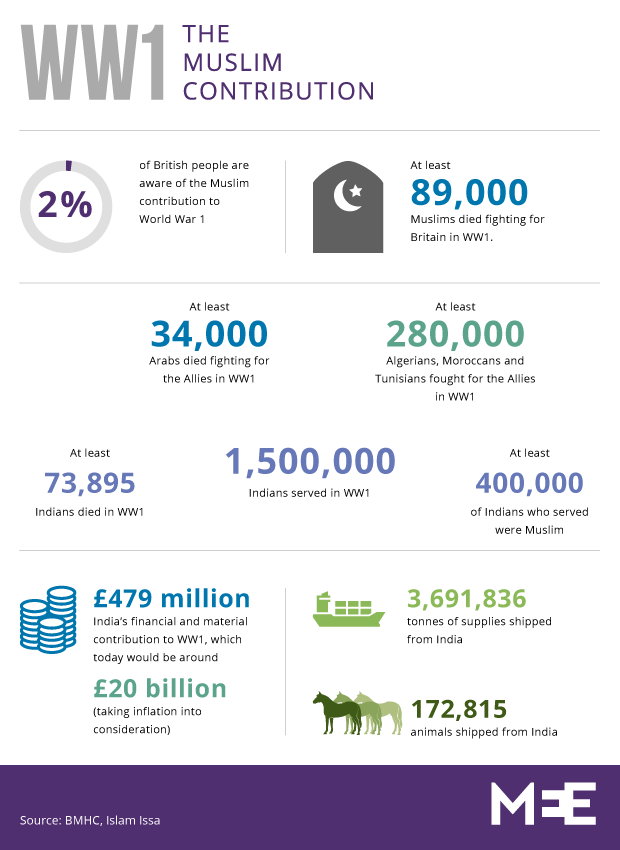

Over twice as many Muslims fought - or supported - Britain, France and the Russian Empire during World War I than was previously thought, according to new research.

The research also reveals the surveillance techniques used by army authorities to detect what they were already calling “Islamic fanaticism” and to prevent Muslim soldiers from defecting to the Ottoman-allied German forces.

The findings stem from research commissioned by the British Muslim Heritage Centre, a Manchester-based centre that is hosting an exhibition detailing the contribution of Muslims to the Allied war effort.

At least 885,000 Muslims were recruited to fight for the Allies - including Britain, France, the Russian Empire and the Kingdom of Hejaz (now western Saudi Arabia) – against Germany, the Austro-Hungarian Empire and Ottoman Empire.

Of these, over 89,000 are known to have been killed during more than four years of a grinding war of attrition.

The contribution of Muslim soldiers, mostly from India but also from other colonised countries like Egypt, Algeria and Tunisia, to the eventual Allied victory had until now been much less well-known than their role in the World War II.

Islam Issa, a lecturer in English Literature at Birmingham City University who led the research, told Middle East Eye he had sifted through “thousands" of letters and secret internal army documents to find archival traces of the tens of thousands of Muslim soldiers.

Letters sent by Indian soldiers on the Western Front to family back home provided much of the material for the research.

Many of these letters are now available to researchers thanks only to a strict censorship regime that was set up to monitor Muslim soldiers and stop them from defecting to forces fighting alongside the Ottomans, who at the time “represented Islamic power,” Issa said.

“Interesting letters originally in languages other than English would have to be translated for the censors. Some were from people who had deserted, trying to get their former comrades to do the same. [The censors] were basically on the lookout for what they called ‘Islamic fanaticism’."

“Looking at it and the bureaucracy surrounding it, you realise that not too much has changed.”

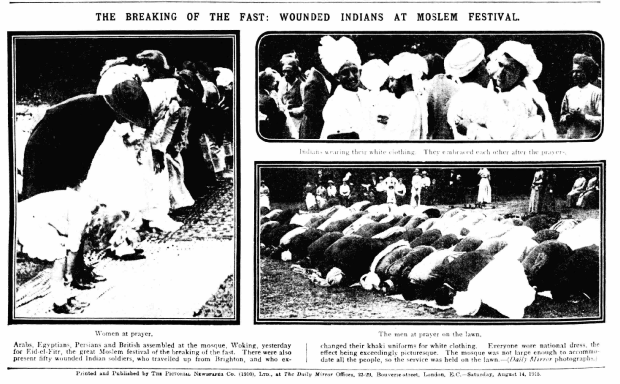

Though the justifications for state surveillance of Muslim lives resemble those of today - namely countering "Islamic fanaticism" as it was then called - the documents revealed a very different approach to countering it: army authorities and the British press at large went to great pains to court Muslims who were supporting the Allied war effort.

“[Army authorities] realised it was a huge amount of manpower - having Muslim soldiers on side would be a massive asset. There were examples of them trying to be culturally sensitive and offer them space to complete their religious rites.”

Regimental diaries from battalions with predominantly Muslim soldiers note efforts to make sure the men had space to pray and enough Islamic books. On some occasions soldiers were given special permission to pray en masse on the decks of warships.

The British press - an integral propaganda arm of the British war effort - was “interestingly tolerant [of Muslims] for the time,” Issa said.

While the British press was generally positive about the Muslim contribution to the war effort, he said, “there are some overlaps with modern coverage. The word terror was used – but it was intended to be positive. They were said to be invoking terror on ‘our’ enemy.”

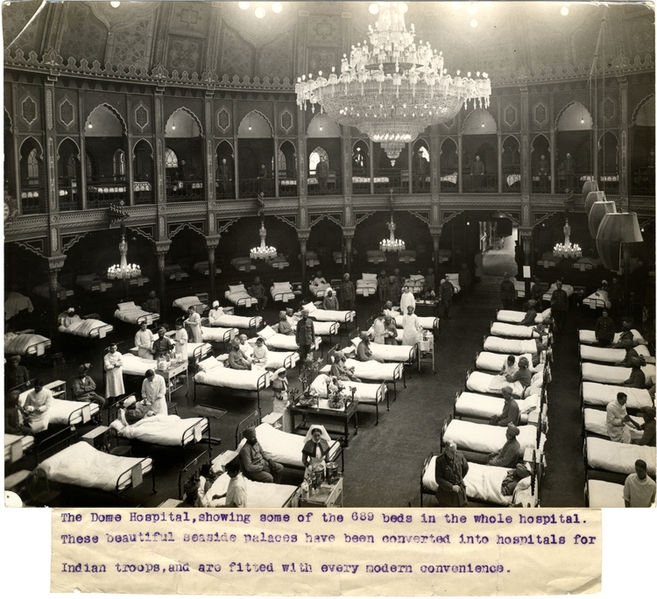

The British authorities, and their press, took great interest in the good treatment of wounded Muslim soldiers. King George V would regularly visit Brighton Pavilion, an ornate seaside palace - styled on the Taj Mahal – that had been turned into a makeshift 722-bed hospital for Indian soldiers. A separate kitchen prepared halal meals for the Muslim soldiers, and pork products were banned from the grounds. By the end of the war, the army had sold 120,000 commemorative postcards depicting the soldiers convalescing in their decadent temporary surroundings.

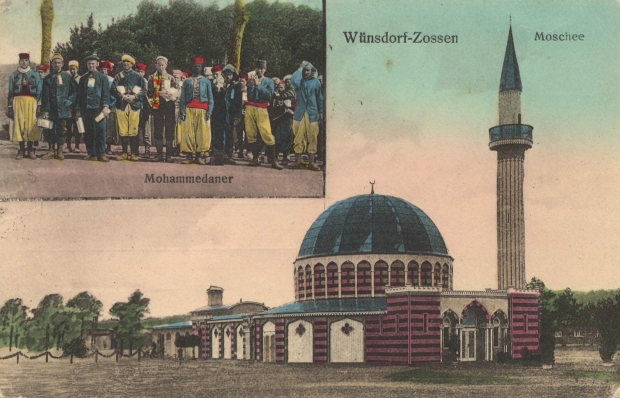

British efforts to court Muslim soldiers were matched by those of arch-rivals Germany. In 1914, just months after the outbreak of the war, authorities built the Half Moon Camp. Some 30 kilometres south of Berlin, the camp was specifically designed to house thousands of Muslim prisoners of war from the Allied side. It was also the site of the first purpose-built mosque in Germany. Based on Jerusalem’s iconic Dome of the Rock mosque, the wooden building was completed in July 1915.

A decade later, the once-ornate structure would be torn down due to disrepair. While it was in use, though, the mosque served as a focal point for German-sponsored Islamic preaching aimed at convincing the POWs that being a good Muslim meant fighting for the Ottomans.

An account from 1982 notes that the Tunisian mufti Salih al-Sharif al-Tunisi – who also served in the Ottoman intelligence services - arrived to preach djihad (sic) and attempt to persuade the camp’s “inmates” to switch sides and start fighting the French. Tunisi went so far as to start a newspaper, al-Djihad, aimed specifically at the Muslim POWs. Tunisi’s support was so much in demand that, after his return to Istanbul, German authorities set about finding ways to convince him to return to the camp to continue preaching.

As a result of initiatives like these, says Issa, “the British had no option but to increase their propaganda and court the Muslim soldiers”.

By the end of the war, at least 89,000 soldiers listed as Muslim in army records had been killed. The largest memorial to them in the UK is in the small Surrey town of Woking. Britain’s War Office established a special burial ground for Muslim soldiers at the site – close to the UK’s only purpose-built mosque at the time – after rumours spread among troops that those killed were not being buried according to proper Islamic rituals.

Many of those who survived the war returned to their homes and slipped from the Western historical record – with their letters no longer subject to army censorship, archival traces of their lives mostly dried up.

Even to relatives, said Issa, many of the soldiers spoke little about their experiences during the war. “One person told me they never heard any stories from their grandparent who had fought in WWI - he said he just wanted to forget it.”

Some survivors, though, would end up back in army uniform two decades later, fighting for the Allies again in World War II.

The Stories of Sacrifice exhibition will be open until 1 July 2016 at the British Muslim Heritage Centre's site in Manchester

Middle East Eye propose une couverture et une analyse indépendantes et incomparables du Moyen-Orient, de l’Afrique du Nord et d’autres régions du monde. Pour en savoir plus sur la reprise de ce contenu et les frais qui s’appliquent, veuillez remplir ce formulaire [en anglais]. Pour en savoir plus sur MEE, cliquez ici [en anglais].