Osama bin Laden casts long shadow, 5 years on

NEW YORK, United States – Upon learning of Osama bin Laden’s death, New Yorkers headed to the site of the toppled World Trade Center towers and cheered the killing of a bogeyman with raucous renditions of the Star Spangled Banner and chants of “USA, USA!”

The raid on bin Laden’s hideout in Pakistan took place on 2 May 2011. US President Barack Obama’s televised address, nail-biting scenes from inside the White House Situation Room and the street mayhem in Washington and New York are all etched in the national memory.

Five years on, life at the World Trade Center – a target of bin Laden’s al-Qaeda group on 11 September, 2001 – has returned to normal. It bustles with workers; tourists marvel at the footprints of the two toppled towers, elegantly refashioned as abyss-like black granite fountains.

“I’m glad they got him, but I don’t think about it much,” Dan Lawless, 61, a non-profit worker from Texas told Middle East Eye, as visitors to the memorial took photos and left rosebuds atop the etched names of some 3,000 victims.

“I don’t think he looms very large. He seems small with everything going on with ISIS,” he added, referring to the Islamic State (IS) group that both hails from and eclipsed bin Laden’s radical Islamist ideology.

Navy Seals flying to bin Laden’s compound in Abbottabad, Pakistan and delivering a fatal headshot marks as a milestone. The 53-year-old had been Washington’s top public enemy for the decade after the 9/11 attacks and the global face of hardline militancy in the name of Islam.

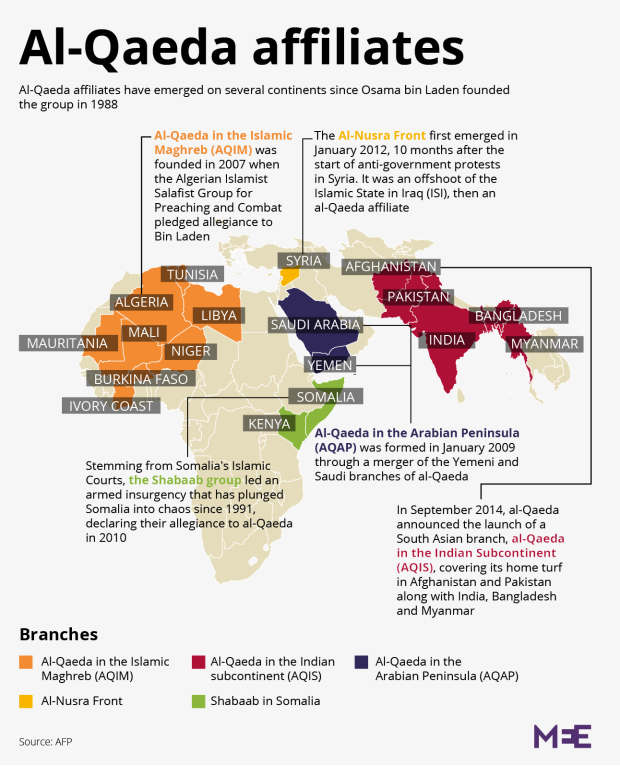

Five years on, the administration is upbeat. Bin Laden “no longer threatens the American people,” White House spokesman Josh Earnest said this month. Al-Qaeda’s core is “decimated” and US-led counter-terror efforts traverse the Middle East, Africa and Asia.

Lingering legacy

But the Saudi-born multimillionaire still casts a shadow over Washington.

The events around his killing remain contested. US relatives of 9/11 victims are causing a diplomatic spat by pushing for compensation from Saudi Arabia, home to 15 of the 19 hijackers. Anti-Muslim rhetoric in the 2016 White House race traces back to bin Laden.

More significantly, bin Laden’s dream of building his version of an Islamic utopia by hitting Western targets and ousting Arab autocrats has inspired the IS group, al-Nusra Front and other rebels in Iraq, Syria, Egypt, Libya and down through sub-Saharan Africa.

“Bin Laden is a ghost. He can haunt us, but his relevance has waned,” Jennifer Loewenstein, a scholar at Pennsylvania State University told MEE. “We’ve slain our dragon, yet nothing much has changed in the world of terrorism, fundamentalism and Wahhabi extremism.”

The circumstances around the raid on Abbottabad, a Pakistan army garrison town, remain contested. Seymour Hersh, a reporter who broke the My Lai and Abu Ghraib stories, released a book this month called The Killing of Osama Bin Laden that disputed the official US record.

The way Hersh tells it, bin Laden fought the Soviet Union as a fighter in Afghanistan and was familiar to Pakistani intelligence. He lived at the hideout in Abbottabad for about five years with the knowledge of Pakistani and US agents.

In the White House version, his compound was found by tracking couriers in an elaborate manhunt, and the Seals had to shoot their way to bin Laden, who used one of his wives as a shield. Hersh, who quoted retired US military intelligence officials, said this story was made up.

Saudi involvement?

It is not the only bin Laden conspiracy. Half-baked theories about 9/11 being an inside job persist, and recent weeks have seen renewed interest in 28 pages of a government report into the attacks that remain classified.

Relatives of 9/11 victims seeking to sue the Saudi government for damages have called for the release of the contentious pages, which, according to lawmakers who have read them, outline official Saudi involvement.

The Office of the US Director of National Intelligence says it is reviewing the material to see whether it can be declassified.

Bin Laden also impacts US politics more subtly. Donald Trump, the frontrunner for the Republican nomination in the 2016 White House race, reopened 9/11 scars in November by saying “thousands of people” in New Jersey had cheered as the towers came down.

The coiffed property mogul went on to call for a bar on Muslims entering the US.

“September 11 remains a feature in US presidential politics. Trump’s repeated lies about US Muslims celebrating is part of his reasoning for a moratorium on Muslim immigration,” Jonathan Cristol, an analyst at the World Policy Institute think tank told MEE.

“Democratic frontrunner Hillary Clinton’s presence in the famous Situation Room photo during the raid on bin Laden’s compound plays to her claim to have the most foreign policy experience, and to her hawkish bona fides.”

But it is through the deadly strikes of IS-linked militants in Paris, Brussels and San Bernardino, California – as well as the myriad religious militants warring in Syria, Iraq and across the region – that bin Laden’s legacy is felt most potently.

'Spiritual grandfather of jihadism'

While IS has stark ideological and tactical differences to al-Qaeda, and many other rebels have local rather than international goals, bin Laden remains the “spiritual grandfather of jihadism,” said analyst Barak Barfi.

“Bin Laden was creative, innovative and ahead of his time. He left one of the world’s wealthiest families to tread a humble, softly spoken path in Afghanistan, reminiscent of the prophet,” Barfi, from the New America Foundation think tank, told MEE.

“Much of the Islamic world still views him as a defender of Muslim rights that are trampled by the West. Americans cannot see beyond his magnum opus of 9/11 to understand the grievances that gave rise to his brand of fundamentalist religious militancy.”

The bloodiest sectarian and religious war currently raging is in Syria, where moderates, Kurds, religious militants, government forces and others fight in a five-year-old conflict that has claimed some 500,000 lives and sent millions fleeing from their homes.

According to Leeds University scholar Hasan Hafidh, the US faces a challenge in defeating IS and sidelining Syrian President Bashar al-Assad without turning to the al-Qaeda-linked groups that could help achieve those goals.

“The US needs to acknowledge that its most imminent problem isn’t necessarily combating al-Qaeda on the ground but rather to devise a foreign policy strategy where they don’t effectively become an asset in such protracted conflicts as Syria and Yemen,” Hafidh told MEE.

Others see different problems in the crystal ball.

“IS may be the greater threat today, but IS believes in the fierce urgency of now. One day, hopefully soon, it will be defeated. Bin Laden had a longer time horizon, and with IS gone, al-Qaeda will again top the headlines,” said Cristol.

“Patience among bin Laden’s followers may be the part of his legacy that comes back to haunt us in the long run.”

Middle East Eye propose une couverture et une analyse indépendantes et incomparables du Moyen-Orient, de l’Afrique du Nord et d’autres régions du monde. Pour en savoir plus sur la reprise de ce contenu et les frais qui s’appliquent, veuillez remplir ce formulaire [en anglais]. Pour en savoir plus sur MEE, cliquez ici [en anglais].