How paralysed London cleric uses social media to help families flee Islamic State

The sun is low in northern Syria near the Turkish border. The growing cold makes Amina and her young sons tremble even more than they already are.

A recent convert to Islam, she travelled east with her family to make a fresh start in what she thought would be a new utopia - Islamic State’s [IS] self-declared caliphate, an attempted revival of the hallowed institution which ran Islam for more than one thousand years.

Or that’s at least what he told her.

Eventually he confessed: he had found another woman. Abandoned, Amina was left to fend for herself and her children in a country she did not know, reliant on a group responsible for multiple and repeated instances of murder, rape, torture and brutality. Now single, she has been confined to an all-woman dormitory by the IS authorities and kept under close guard.

Amina tried to escape before – and failed. She knows that if she is caught again, then her captors will likely show no mercy and kill her.

Later, she will learn that she and her sons are narrowly heading into one of the many minefields that dot the region

But the guards are not always vigilant. Amina sees an opportunity. She takes a risk, and she and her three children flee on foot late one afternoon into the gathering dark.

“I ran like hell,” she later tells MEE. “I did not see many houses, just open land.”

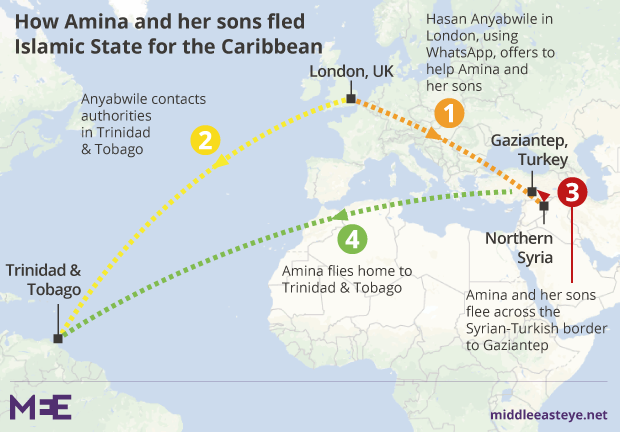

Three hours later, as night falls, they approach the Turkish border close to Gaziantep, a city in western Anatolia.

Soon, Amina can hear the Turkish soldiers calling out to her, and runs towards them in a last dash for freedom. Later, she will learn that she and her sons narrowly avoided heading into one of the many minefields that dot the region. The sentries were trying to warn her to slow down.

Amina will stay in Turkey for a few months, then head home to Trinidad and Tobago – some 6,000 miles away. She is one of more than 100 young Trinidadians who left for IS’s "caliphate" since it was declared in 2014.

That Amina and her sons were able to escape - indeed, are still alive - is because of Hasan Anyabwile, a wheelchair-bound cleric who resides in London.

The room of books

I find myself at the door of a large semi-detached house in a leafy west London suburb.

It's a two-hour journey across the metropolis to get here. The last leg of my journey, a bus ride, takes me past Victorian-era brick factories, repurposed chemical plants and a town centre whose skyline comprises the beehive domes of Hindu temples and the soaring minarets of hulking mosques.

The room is darkened by heavy curtains, which block out the afternoon sun, and adorned with artefacts. It is as though I have stepped into an underground cavern somewhere in Africa, the home perhaps of a seasoned hermit.

The man I have come to see tells me that he usually hibernates in here throughout the English winter which is harsh, certainly by the standards of the Caribbean from where he originally comes.

The confined space is dominated by high-rise shelves that cover a wall. As per Islamic custom, its heights are reserved for volumes of sacred scripture whose covers are embossed with golden, swirling Arabic calligraphy.

Immediately Hasan Anyabwile starts talking. I scramble for my notebook as he begins to read off a charge sheet against Islamic State, his eyes intense

Below them are a scrum of books, ranging from Olivier Roy, the French terror expert, to Said Nursi, the 19th-century Kurdish theologian. Black prayer beads have been draped around the handle of a wheelchair that sits beside the bed. I move some papers from a chair to make space to sit down.

On a bed at the far end of the room my host, Hasan Anyabwile, is lit under a lamp, his full lips giving way to a tuft of salt and pepper hair beneath his chin. He heaves his slender legs around so that he can sit upright, propped against several pillows while he clutches a sheet over his slim frame.

Immediately Anyabwile starts talking. I scramble for my notebook as he begins to read off a charge sheet against IS, his eyes intense.

“IS are false,” he says in a well-spoken but characteristically melodious Trinidadian accent. “Targeting of churches goes against the Quran.”

From Caribbean to caliphate

Trinidad and Tobago is perhaps best known for its annual carnival and as the birthplace of calypso.

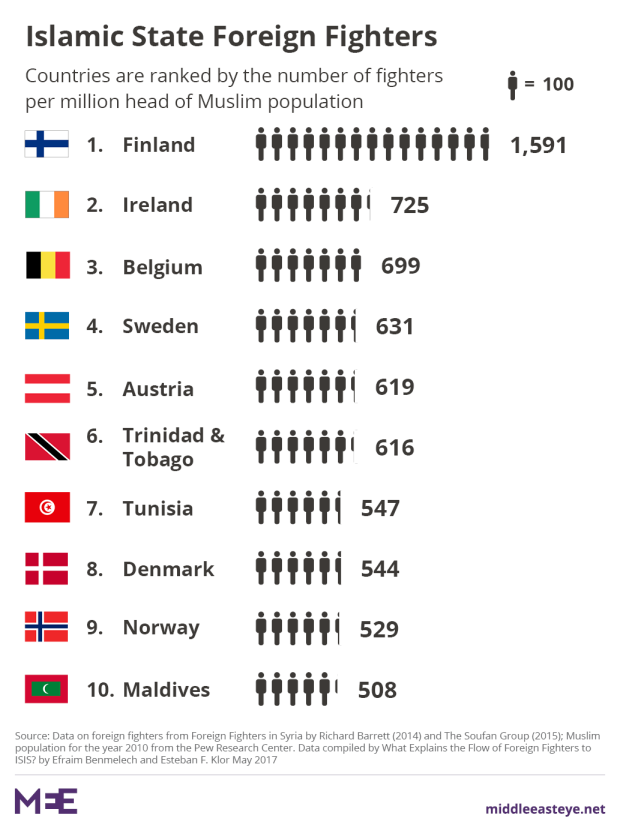

But in recent years the twin-island nation, which has a population of 1.4 million, has earned a reputation for one of the highest rates of IS recruitment per capita (see chart below).

Corruption, murder and inequality have all soared as Trinidad and Tobago’s petroleum-addled economy continues to stall amid low oil prices. And so IS, through its media arm, has tapped into a rich vein of disillusionment among the islands' Muslim community, which makes up five per cent of the population.

Trinidadians have lined up in IS videos to decry the supposed ills of their western society, and encourage their compatriots to join them in their supposed Islamic shangri-la.IS poster boy Shane Crawford sent shock waves through the country in 2016 when he appeared in the group’s flagship Dabiq magazine and called on IS sympathisers to attack non-Muslims.

Crawford is said, like others who have joined IS, to have been involved in Trinidad and Tobago’s gun-toting gangs, many of whom took on an Islamic identity. He said he left as “one of our goals was to...join the mujahidin [fighters] striving to cleanse the Muslims’ usurped lands of all apostate regimes.”

Shane Crawford is now dead.

Almost 30 years ago, Anyabwile was one of the masterminds behind an attempted coup in Trinidad and Tobago, before he was shot and left paralysed from the waist down after his group descended into chaos.

Like Amina, Anyabwile too was forced to flee - but this time from Trinidad to the UK. His story is a chronicle of political Islam in the Caribbean state.

The conversion to Islam

1974: Beville Marshall - as Anyabwile was known as a boy - arrives at his neighbourhood mosque in Victoria Village, a neighbourhood in the country's industrial heartland of San Fernando, clutching a letter addressed for the imam. It bears a signature from his parents, permitting him to undergo a small - but life changing - religious ceremony.

But the imam is nowhere to be seen.

Some men sitting in the mosque are members of the Tablighi Jamaat - a global Islamic faith renewal movement. They break the news: the imam died during the night.

After Marshall shows the letter, one man steps forward and asks him to repeat the Arabic words of the shahadah, which will convert the boy to Islam. Anyabwile is 12 years old.

Anyabwile joined the Black Power protests which brought the country to a standstill through worker strikes, an army mutiny and guerilla attacks. But he refused to join the Nation of Islam because he could not accept their theology, and instead accepted Sunni Islam.

Anyabwile’s family, who were Christians, began to cook halal meat and sew him a “jalab” gown. His grandmother would even make fried bread for his Ramadan fast. “I became a Muslim before I was a teenager, so I understand a lot of the problems we face in a non-Muslim society,” he says.

Islam in Trinidad and Tobago had always been the preserve of the descendants of Indian indentured servants who came during the 19th century to replace emancipated black slaves in the sugar-cane fields.

But the Islamic Party, which Anyabwile joined in 1977, brought a fresh approach, proselytising among poor, urban black communities and explaining that their forebears, African slaves, might have been Muslim.

He refused to join the Nation of Islam because he could not accept their theology, and instead accepted Sunni Islam

The party wanted to build a new Madinah, based on the Prophet Muhammad’s original Muslim community. But their attempt to obtain land in Guyana was turned down by the government, which became nervous after the Jonestown mass suicide in Guyana in 1979 left more than 900 people dead.

In 1982, Anyabwile joined the Jamaat al-Muslimeen (“the community of Muslims”), led by Yasin Abu Bakr, a charismatic student of Black Power and his group began making plans for a Muslim village on the edge of Port-of-Spain.

Anyabwile had a quick rise through the ranks of the Jamaat, which Danjuma Bihari, a London-based scholar, likens to that of Malcolm X's ascent through the Nation of Islam.

Anyabwile’s family connections may have helped: his wife is the sister of fellow jamaat leader Bilal Abdullah. She was once married to Darcus Howe, the London-based Trinidadian black civil rights activist who died earlier this year.

Kwesi Atiba, a Trinidad-based imam, first met 14-year-old Anyabwile in the 1970s. “I've seen a lot of young people over time, they come in, they're young, they get distracted. They want to go play football, go play cricket.

"He thought you need to be doing something to improve the condition of people.” He describes Anyabwile today as “very, very active, extremely active.”

The coup that rocked a country

During the 1980s, the Jamaat filled in for government failures in poor black communities, cracking down on drugs dealers, providing medical care and fighting gang violence.

The Jamaat’s reputation saw it come into conflict with the authorities, which said that its compound - now a thriving village - was illegal. The group insisted that the land had been given to them by a previous government.

Police raided the land, seized weapons and killed Jamaat members.

Footage shows a lawmaker interrupted by loud banging mid-speech, holding a paper in his hand. He continues, then freezes. Politicians scramble beneath tables or behind pillars. Gunshots ring out. A man dressed in fatigues jumps into view, shouting and waving a rifle.

After six days of violence, 24 people were dead, the Jamaat’s village was reduced to rubble and the coup leaders were in prison.

In 1992, Abu Bakr and his co-conspirators were freed – but on release found a very different Jamaat al-Muslimeen. Former gang members had taken over the rudderless group, promoting the sort of behaviour - drug trafficking, extortion and further extortion - it had tried to eradicate during the 1980s.

To wrest back control, Anyabwile became the Jamaat’s head of security. He also taught himself Arabic and took only a year to complete a three-year course and become a qualified Islamic scholar at a local Deobandi seminary, an Islamic movement based in India.

Daurius Figuera, a Trinidadian scholar, says: “He started to speak as a trained Islamic scholar - that was the major difference between the Anyabwile before 1990 and the Anyabwile after.”

But Anyabwile's rise through the Jamaat brought him into conflict with Yasin Abu Bakr.

'The Jamaat is like Hotel California - you can never leave'

- Danjuma Bihari, London-based scholar

Bihari, who has known Anyabwile since the 1980s, regularly appears at Speakers’ Corner in Hyde Park, wearing a west African Dashiki and kufi cap. In 2002, when Anyabwile came to London, he urged him to leave Trinidad and further his studies in Africa.

“I think whatever you can do for Trinidad is exhausted,” his friend advised. “As far as Yasin is concerned you are not only a threat, you are a rival.” Anyabwile was tempted, but said he was needed back home.

And then his life changed.

One July morning in 2002, Anyabwile rose early to pray at his home in Belmont, a warren-like neighbourhood on the fringes of Port of Spain. As he passed a window, he spotted a man stood on a church balcony outside, taking aim.

Anyabwile immediately killed the lights and fled into another room but was still hit four times. He has not been able to walk since.

He eventually sought treatment in London and was granted asylum in 2003, after he gave assurances to security services that he would not oppose the British government.

Anyabwile says the Jamaat were behind the shooting (it has not been proven in court). “I know it’s them. It’s political violence,” he says. “I’ve gone past that now. I leave it in the hands of Allah.”

Bihari adds: “The Jamaat is like Hotel California - you can never leave.”

The social network

Anyabwile is still living in London, yet social media allows him to remain active in Trinidad. IS has thrived globally. Traditional Islamic scholars struggle to reach a generation who spend more time on Snapchat than in mosques.

And so Anyabwile, plain-taking and social media savvy, garners a following in Trinidad that conventional scholars could only hope for.

He appears in one of his YouTube videos in a baggy white jubba with a neckline embroidered in gold thread, saying that the jihad in Syria is not rooted in the Islamic tradition.

“Don’t get involved,” he warns from behind dark-tinted glasses. “Even the Pentagon groups are fighting against the CIA-backed groups.”

His Facebook page, peppered with posts on African culture and history, is a reminder of his appeal to young, black converts to Islam, who are over-represented among those who have left for Syria. A black person travelling to Syria, he says in one video, “is like being a cockroach in a fowl’s party.”

Bihari borrows a term coined by Olivier Roy to describe Anyabwile: "He understands that what we're seeing today with IS is the islamisation of radicalism, rather than the radicalisation of Islam."

When IS declared its caliphate, Anyabwile used Islamic holy texts to question its authenticity. He concluded that it could not exist because it advocated excommunicating Muslims and did not prove it had the consent of the people to govern.

His concern grew as a slow-drip of mostly male Trinidadians heading for Syria became a steady stream of whole families, including women and children. Anyabwile heard of young children killed by mishandling weapons or walking over mines. “It was still effectively a war zone and unsafe for women and children to be living in,” he says.

When those who left Trinidad and Tobago wanted to come home, Anyabwile's service soon became much more urgent

Idealistic adventurers from rich families; ex-offenders converts in search of personal redemption; rum-drinking ravers who seldom prayed - all were taken in by IS’s message and left the Caribbean

They were prodded along by “sheikhs” – as Anyabwile calls them - inhabiting the dark corners of the web. “Those who went had good intentions, but were sincerely wrong,” he says.

To stem the flow and smoke out their recruiters, Trinidad and Tobago’s government has proposed tough counter-terrorism laws, although it is still not illegal to join IS.

Through Whatsapp, Anyabwile first intended to offer religious clarification for why they should not go. He only managed to persuade one person to stay. But when those who left wanted to come home, his service soon became much more urgent.

Anyabwile’s followers put him in touch with Amina in 2015 just before she left Trinidad and Tobago. Much to her husband’s annoyance, they kept in contact when she arrived in Syria. After urging Amina to flee, Anyabwile used his contacts to find her birth name. He next sought help from a woman who had escaped IS before, then liaised with a government contact in Port of Spain to get Amina out.

Amina has returned to the Caribbean, although is finding life hard. “I am yet to settle back in ‘life’ as they call it,” she says.“Brother Hasan has been a great support for me, being there for me to talk to.” Her ex-husband remains in Syria, although Anyabwile does not know if he is still alive.

A Trinidad and Tobago government source told MEE that women like Amina are treated as trafficked victims, not criminals. After they are discreetly flown home they are screened, interviewed and counselled before re-integrating back into society.

Gary Griffiths, the former minister of national security, told MEE last year: “There are many who have returned from Syria who are not terrorists. It doesn't mean they are enemies of the state.”

'Those who didn't go idealised those who went'

Then there were those Trinidadians who left for Syria but stayed in touch and offered Anyabwile insight into everyday life in IS-held territory.

They include Abdul Hakim, not his real name, 25, who was repeatedly jailed on the island for weapons-related offences. Faced with a court case he thought he could not win, Hakim fled to Syria.

Despite having memorised the Quran, he was prepared to look for religious rulings from scholars who would validate his thinking. "He ended up in Syria and when the reality hit him and everything was not as it seemed, he tried to leave,” Anyabwile says.

IS refused to return his passport. Trinidadians in Syria accused him of spying. Abdul Hakeem was in danger. He turned to Anyabwile for advice but had to take care, concealing lengthy conversations by regularly switching phones, keeping ahead of the IS authorities and coalition forces.

News also reached Anyabwile that Trinidadians in Syria resented his influence. “They’re talking about you, they don’t like you,” Hakeem told the west London cleric.

Eventually Hakeem paid smugglers to get him into Turkey, where he was detained by the authorities.

The Trinidad and Tobago authorities would not let him come home – but his family wired enough money for him to bribe prison guards and buy a false passport to get out of Turkey.

Where is he now?

“I heard he went into Africa,” says Anyabwile.

Do men like Abdul Hakim pose a threat if they return home?

Anyabwile acknowledges that some Trinidadians “are still seeking martyrdom,” but says that Abdul Hakim and others he spoke to “never went there to fight.”

News also reached Anyabwile that Trinidadians in Syria resented his influence. 'They’re talking about you, they don’t like you'

"Some of them are still seeking martyrdom so are staying there for the long haul."

But what about the likes of Abdul Hakim?

“He went there to start a new life but couldn’t go forward with putting his life behind the movement.”

Instead, the bigger threat, he says, could come from IS sympathisers who were unable to leave for Syria and who are still at home. “Those who didn’t go [to Syria] idealised those who went.”

Did the coup spark the exodus to Syria?

Anyabwile tells me that his current activities are a continuation of his work in the Jamaat, when he would counsel newlyweds, teach school dropouts and arrange football matches. “Those who go to join IS are my people, I know them,” he says.

“They know there is one person who they can come and ask anything. I do it because I’m a Muslim. It’s just a different type of work.”

Faris al-Rawi, Trinidad and Tobago’s attorney general, told MEE last year: “The jihad cause is romanticised by persons leaning towards Islam of the type seen in the 1990 [coup attempt].”

And Griffith, the former minister of national security, has said that today’s foreign fighters share “the same ideological vein” as coup participants.

This point is underlined by the modern-day inner-city gangs which take on an Islamic identity, young bearded men strutting the streets in flowing “jalabs”

Dion Phillips, a sociologist at the University of the Virgin Islands, told MEE that the 1990 coup was "terrorism", adding: “Despite Anyabwile’s fall-out with the Muslimeen, his incessant fear for his life and alleged denunciation of violence, he is still seen as an extremist to this day,”

Phillips says that an an inquiry into the coup blamed Anyabwile for organising explosives to blow up the police HQ and left a car bomb outside the state TV station.

'Despite Anyabwile’s fall-out with the Muslimeen, his incessant fear for his life and alleged denunciation of violence, he is still seen as an extremist to this day'

Dion Phillips, sociologist

In contrast, Daurius Figueira, a Trinidadian scholar who has written about the coup, says that people headed for Syria because of the Jamaat’s failures. “Some Trinidadians have felt a need to embrace IS because they no longer see the Jamaat as the exemplars of jihad because their coup failed,” he explains.

Anyabwile is more circumspect about the coup and his role, saying that it resulted from political necessity and self-defence, rather than an attempt to rule.

“It was a war. They attacked us and we attacked them. We didn’t go out looking for war with them.”

He says that the majority of those who went to Syria are from prominent Indian Trinidadian families who were more secretive about their actions, and therefore less reported on.

But while he does not regret his part in the coup, he regrets what the Jamaat could not achieve. Had the Jamaat invested in more in young people, “far fewer people would have left for Syria."

The future back home

The final time I meet Anyabwile is shortly after the July anniversary of the 1990 coup. I find him embroiled in a war of words with the Jamaat that has made headlines in Trinidad and Tobago.

In an open letter posted on Facebook, Anyabwile describes the Jamaat compound as “a place that will ensure a future for our youths who don’t have to run to Syria behind a false flag”.

The compound, he adds, belongs to members of the Muslim community and not to one family.

“Envy and jealousy are the tools of the devil,” he writes on Facebook in response, “as much as you mask it in pretty words and Islamic rhetoric.”

Anyabwile’s post also reveals how disability has changed his life. “The pain plus being a paraplegic is very difficult,” he tells me. "It affects everything. It affects your social life, family life, everything. It’s difficult to work. ”

It took him three years to physically heal from the cuts and sores from the shooting.

“I think the mental adjustments haven’t really stopped as yet,” he says in a low voice. “It’s not an easy road.”

'The pain plus being a paraplegic is very difficult. It affects everything. It affects your social life, family life, everything. It’s difficult to work'

- Hasan Anyabwile

Back in the 1990s, Anyabwile had risen to become one of the pre-eminent political operators of his day. He dared to take on the powers that be. But the shooting forced him into a unceremonious retreat - to London, where his life has become increasingly isolated.

In 2015, UK press seized on Anyabwile’s links with the Jamaat, alleging he was appointed imam at the An-Noor mosque in west London after the previous office-holder, Abdul-Hadi Arwani, was killed in a hit organised by the mosque owner Khalid Rashid in 2016.

Anyabwile denies the claim and says that while he was a director and taught at An-Noor, he distanced himself from it shortly after the killing. But press reports have caused teaching opportunities to dry up over the last few years. Once at the centre of events, he is mainly confined to his bedroom, peering at the world through the cracked screen of his iPad.

There is a bitter-sweet irony: in the years that his disability and exile have forced him to channel his message through social media, young people have flocked to the likes of WhatsApp.

He uses the platform to help – and keep in check - his young followers, Skype and Youtube as replacements for the Jamaat classroom, and Facebook Messenger to resolve marital disputes

But he has faced difficulties making contact on the ground in recent months. Back in Trinidad and Tobago, the Jamaat still remains the nominal leader of the country’s black Muslims but its influence is waning, as indicated by the diminishing rows of men who line up to pray behind Abu Bakr each Friday.

Now in his mid-70s, Abu Bakr is taking on less work and pushing his son, Fuad, to the fore. Yet wily pretenders are waiting in the wings, Trinidadians have told me, and are acutely aware that a power vacuum is expanding as Abu Bakr’s age advances. A vicious succession crisis could soon loom.

Some may see him as a successor to Abu Bakr, but Anyabwile is instead reviving an educational institute he set up in southern Trinidad shortly after leaving the Jamaat.

It will teach Islamic studies, history and culture, he says, giving young Trinidadians a sense of purpose and keeping them away from the likes of IS.

He says that while living in the UK has helped him to internationalise his outlook, he still wants to feed his experience back to Trinidad, returning home despite his physical constraints to lead the group. “I’m not really an armchair scholar. I bring knowledge alive in forming a community and helping people.”

He reflects again on the coup and his life since. “I am not a violent person,” he says. “But if something calls for violence, then…”

He breaks off and pauses.

“I would rather peace rather than war.

Middle East Eye propose une couverture et une analyse indépendantes et incomparables du Moyen-Orient, de l’Afrique du Nord et d’autres régions du monde. Pour en savoir plus sur la reprise de ce contenu et les frais qui s’appliquent, veuillez remplir ce formulaire [en anglais]. Pour en savoir plus sur MEE, cliquez ici [en anglais].