Party in a hard place: Turkey’s HDP and the peace process

ISTANBUL - Tuncer Ozdogan is a sober, unassuming man of 56. His coat had hung about him like a too-short turtle shell as he came in the cafe from a wintry Istanbul morning.

He spoke freely but his only laugh seemed to be reserved for a question about whether he was angry at being jailed for a total of eight years for his politics - the first time for his Marxist sympathies in the 1980s and, more recently, for his work with the Peoples’ Democratic Party, or HDP.

“No,” he said with a shrugging smile. “Everyone has a role to play.”

In 2011, Ozdogan was a philosophy teacher at the ‘Politics Academy’, a further education institution run by the HDP (then better known as the BDP), when police arrested him at home in a 4am raid.

Turkish authorities had been bugging his classroom and tapping his phone, which later allowed prosecutors to say that Ozdogan “expressed sympathy” for the PKK in his lectures. Under Turkey’s expansive terrorism laws he was charged as a “leader of an armed terror organisation”.

Ozdogan was one of approximately 8,000 members of Kurdish civil and political groups jailed between 2009 and 2014 on similar grounds. In 2012, these prisoners went on a dramatic hunger strike - an event that proved to be the curtain-raiser for the government’s revelations it had begun negotiations with Abdullah Ocalan, the Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK) nominal leader who is currently held in a Turkish prison.

A triangle of power

The HDP’s role in general is to represent the Kurdish national movement in the Turkish parliament. Through this, it has also been playing a central role in one of the most consequential government policies in the Turkish Republic’s history - the efforts to negotiate a political settlement to the PKK insurgency and will also be facing a major test in the upcoming June elections when it is hoping to make a large impact on the electoral scene.

Forty-thousand guerrillas, conscripts, commandos and civilians have been killed since the PKK first attacked Turkish soldiers in August 1984. With general elections scheduled for this summer and the Syrian civil war greatly increasing tensions in Turkey - especially in the country’s predominantly Kurdish southeast - negotiations are at a crucial stage.

A joint government-HDP declaration outlining negotiation terms was expected last week after days of intense meetings. But no statement was made, leading to recriminations on both sides.

The HDP has so far occupied a somewhat odd spot in these peace negotiations. Though it is a legal, parliamentary party, it remains a junior partner to the outlawed PKK.

“There is a triangle of authority in the Kurdish movement,” Mustafa Akyol, a Turkish writer and journalist, said in a phone interview.

At one apex of the movement there is the HDP, at another is the PKK leadership-at-large based mostly in northern Iraq’s Qandil mountains, and at the third is the PKK’s nominal leader Abdullah Ocalan, who has been incarcerated in a Turkish prison since his dramatic capture in 1999.

“So who do you talk to? Ultimately the PKK makes the decisions, and that means that everything ultimately comes down to Ocalan. The government has clearly determined that Ocalan is the key,” Akyol said.

So far in the negotiations, HDP leaders have served most conspicuously as messengers between Ocalan, Qandil and sometimes the government. But as the public face of Turkey’s Kurdish movement, the HDP must wade deeply into the harsh, public polemics that characterise parliamentary politics and, in particular, what is known in Turkey as the “Kurdish question”.

The talks have been stalling and lurching forward since 2012. The current hope is that the two sides will come to a compromise agreement that Ocalan will be able to announce an end to the PKK’s armed insurgency from his prison cell on Newroz (21 March, the Middle Eastern New Year). Last week’s breakdown of talks, however, put this timeline in doubt.

Peace plan

In late November 2014, Ocalan gave a HDP delegation a draft of his negotiation plan. The details are still secret, but it is widely believed that the key issues include amnesty for PKK fighters, the prospect of freedom for Ocalan himself and - most importantly - political autonomy for the Kurds.

Though Kurdish leaders no longer demand their own country, many Turks remain suspicious of the bargain being driven by Ocalan and the government.

“About half the population believes there is a hidden agenda,” said Professor Hakan Yilmaz of Istanbul’s Bosphorus University and leader of a recent survey on public opinions on the talks.

“This [suspicion] is quite alarming. Normally a ‘peace process’ should appeal to everybody. But because the government couldn’t sell it to the [whole] public the peace plan is perceived not as a state policy but as a party policy,” Yilmaz said in the telephone interview.

HDP and governing Justice and Development Party (AKP) voters are generally for, and other voters generally against the negotiations, Yilmaz explained.

And there is a significant split between the two negotiating sides, the HDP and the AKP, Yilmaz added. Both Turks and Kurds in the general population have “pretty limited” expectations regarding what a peace settlement should deliver, namely, an end to the armed conflict, economic development, with a “significant minority” demanding some improvements in the areas of cultural rights, Yilmaz said.

Knowing this, the AKP government might be tempted to deliver a “minimum package”, that is, a settlement that does not address demands for amnesty, Ocalan’s status, or autonomy, and “buy [themselves] five to ten years of time,” Yilmaz said. “For the HDP such a minimum package could be perceived as a defeat.”

In or out of parliament?

The HDP recently announced its plans to contest June’s election as a party. The strategy could give the party greater leverage over the government and the peace process, and significantly, over its PKK comrades.

In Turkey, political parties getting under 10 percent of the total vote cannot enter parliament. Until now, politicians from the HDP and the party’s predecessors have circumvented this obstacle by running as independents, to which the rules don’t apply. But with no guarantee that the party can surpass the 10 percent threshold, questions have been raised about the gamble. Others see it as a smart move.

“For the first time a [legal Kurdish political party] will show its real strength as a political force,” Hakan Yilmaz said. “Getting nine percent of the vote as a party - even if they do not enter parliament - will provide more leverage in negotiations than having 30 independent seats with six percent of the vote,” Yilmaz said.

Getting nine percent and being barred from parliament would also serve the HDP in powerfully challenging the legitimacy of parliamentary power, something that no doubt worries the government.

“The HDP’s power is not only in parliament but its power is also in the streets,” Yilmaz said. Failing to surpass the threshold also carries the implicit threat that the Kurdish movement could unilaterally declare autonomy in predominately Kurdish areas of Turkey.

At the same time, passing the threshold is not unimaginable.

In last year’s presidential election, HDP candidate Selahattin Demirtas performed better than expected, collecting almost 10 percent of votes by appealing to voters beyond the Kurdish movement.

“There is a legacy of sympathy among Turkish leftists and many liberals for the Kurdish movement,” Akyol said.

“Demirtas further increased that sympathy by identifying himself as the [2014 presidential] candidate that will defend all the oppressed in Turkey. He used language that was not just pro-PKK but broader.”

Inclusive or Kurdish?

The HDP is now home to nearly two dozen activist groups. Environmental, labour, and LGBT rights are central to party rhetoric. Kurds, Turks, and Armenians all fill party ranks.

Sirri Sureyya Onder, a HDP member of parliament and Abdullah Ocalan’s primary interlocutor is a Turk, not a Kurd. In last year’s local elections, the HDP contested every mayors’ chair with co-candidates - one man and one woman on each joint ticket.

For Ozdogan, his party’s emphasis on diversity is more than electioneering. It reflects an evolution from what was initially a separatist, dogmatic Marxist movement.

“In the 1970s, the Kurdish movement emerged as a Marxist movement, and was thus plagued by the same problems as Marxism was … Marxism ignores diversity,” Ozdogan said.

The HDP of the 21st century is trying to change that, he added. “Kurds want to live with everyone.”

However, the HDP’s broadening of support presents a potential dilemma that has not been missed by observers.

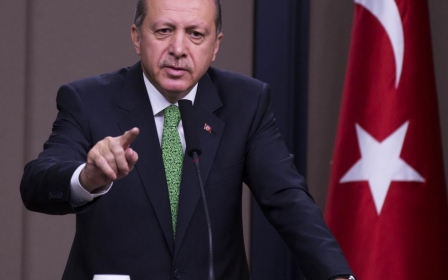

The HDP can make it into parliament only with the support of voters not directly tied to the core Kurdish movement. Once in parliament, the AKP government will want the HDP to pass a new constitution - which is expected to give Turkish president Recep Tayyip Erdogan executive powers - in exchange for Kurdish concessions. Such powers for Erdogan is anathema to those non-core supporters that will have empowered the HDP, leading observers to question if the HDP will be able to stay true to its broadened appeal.

Diversity and division

At the same time, the HDP’s inclusive rhetoric has not bridged deep divisions within Kurdish society. Surprising to some, most Kurds do not vote for the HDP, but for the governing AKP. (Also the AKP would sweep up all the HDP’s parliamentary seats if the party fails to top the 10 per cent threshold in June.)

In addition, the Syrian civil war has fuelled more dangerous divides in Kurdish society. Mirroring the Kurdish-Islamic State conflict in Syria’s Kobane, HDP and PKK supporters have clashed in Turkey with Islamist Kurds that belong to the (Turkish) Hezbollah and its affiliate the Free Cause Party (Huda-Par).

Late last year, HDP co-leader Selahattin Demirtas warned of a possible civil war in Turkey. A new security bill tabled by the government threatens to antagonise Kurds further.

Today Ozdogan is a free man. His trial as a “terrorist leader” continues, but it is this precariousness that concerns him most.

“What’s happening in Syria can happen in Turkey,” Ozdogan said. “Go look at the psychology of the people. Go look at how people feel in Yuksekova, in Sirnak [cities in predominantly-Kurdish southeast Turkey],” he said.

“Turkey is really on the edge of a high cliff.”

Middle East Eye propose une couverture et une analyse indépendantes et incomparables du Moyen-Orient, de l’Afrique du Nord et d’autres régions du monde. Pour en savoir plus sur la reprise de ce contenu et les frais qui s’appliquent, veuillez remplir ce formulaire [en anglais]. Pour en savoir plus sur MEE, cliquez ici [en anglais].