Perilous summer for Tunisian migrants

“It’s not easy for migrants to just get on a boat and just go to the sea. You hand yourself to death,” Mohammed Haj Frej says at a cafe in the coastal Tunisian town of Monastir.

Frej knows only too well the risks young Tunisians are taking to try and reach a better life in Europe. Perilous journeys he has attempted in recent years have left him physically injured and mentally shaken.

He tried his first and second crossings in 2008 when he was just 23 – one of a sea of young and often educated Tunisians who attempt the trip. Frej has a degree in IT, but like many other says he didn’t have the right connections to get a job.

While his first two attempts failed, in 2011 an apparent window of opportunity opened. Following the overthrow of President Zine Abidine Ben Ali, rumours began circulating that Tunisian security forces had stopped patrolling the waters and the path to Europe was clear.

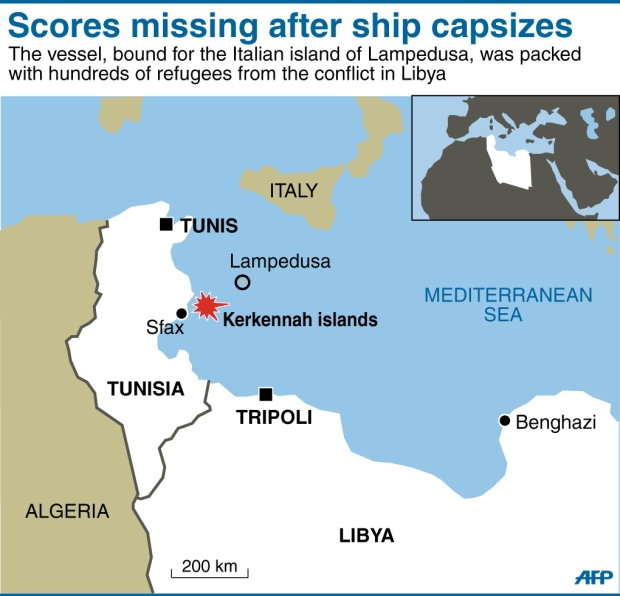

Emboldened by the reports, Frej scrounged 1,500 dinars ($950) and paid the captain of a seven-metre boat to take him from the Tunisian town of Zarzis to the Italian island of Lampedusa. Nearly 200 other Tunisians made the journey with him.

When Frej arrived in Lampedusa on 8 April, 2011, he was placed in a holding centre where rumours quickly swirled that the group would be sent back to Tunisia. In despair, some set fire to their mattresses and revolted.

Authorities then rounded up the detainees and put Frej into the cargo section of a ship with dozens of others. Frej says they remained there for about 10 days. He slept on the floor and occasionally food was thrown down.

“At some point we didn’t really know how many days had passed. We couldn’t tell whether it was night or day,” he says.

Hundreds of migrants have died in recent years as people from across Africa brave the sea passage to Europe, often departing from Tunisian and Libyan shores. Europe has tried using more maritime patrols, but this does nothing to address the poverty fuelling the migration and dozens have already perished this year.

The harraqa

People like Frej are known as “harraqa,” or literally “burners”. The phrase derives from French slang for people who drive through red lights, and refers to those who cross illegally into Europe by ship.

Frej says that after his stint in the cargo section, he was sent to Naples, where he spent three days. On the second day, he tried to run away, but an Italian policeman beat him so badly that his leg required surgery.

On the third day, Italian authorities escorted him to a Tunisia-bound plane but “there was a lot of provocation from police,” says Frej, “so I hit an Italian policeman on his nose and he was bleeding.”

When the pilot refused to let him on the plane, Frej was sent to Gorizia, on the border with Slovenia. He spent nearly seven months in prison there before eventually being shipped back.

Frej’s tale reflects those of thousands of others in Tunisia, and the problem shows no signs of easing.

After the January 2011 popular uprising, the government created a special new migration department under the Ministry of Social Affairs. However, the new government that took power earlier this year disbanded it, leaving civil society groups struggling to fill the void just as the warm weather heralds a new season of migration.

Human-rights groups have also repeatedly criticised Italy for its treatment of migrants. Amnesty International’s 2013 report on Italy noted that “migrant workers were often exploited and vulnerable to abuses,” while a 2012 ruling by the European Court of Human Rights rebuked Italy for its policy of sending asylum seekers back to their country of origin.

Frej claims that during his incarceration he was denied medical attention for his leg, while migrants of European descent received good care.

“For seven months I was sleeping on a metal bunk. My brother came to visit and he was prevented from seeing me,” says Frej, who claims he was racially discriminated against by the guards and can now recite various Italian swearwords and insults which he says were repeatedly hurled at him.

“I think [the Italians] are the most racist people I’ve ever met… We had people from Albania, Poland, from Slovenia but they don’t treat them with as much cruelty, Sometimes I would stay in the cell a week, 10 days, then they would put me in solitary confinement, just like that.”

Despite the hardship though Frej managed to make it back alive and considers himself one of the lucky ones.

Fatima Cherni, from the interior town of Kef, says that her brother Mohammed left for Italy without telling his family in March 2011, 10 days before Frej made his trip. After three years of seeking news of her brother, including from the new newly formed Ministry of Migration, Cherni and her family are still waiting.

“We haven’t received any response from the Tunisian government or the Italian government as to the state of our boys, despite the evidence we presented to them showing his arrival, along with five others, to Italy on 30 March,” she says, referring to a video she watched that she claims shows her brother.

“I’m not speaking only in my own name for my brother, but on behalf of 510 mothers who lost their sons over the last three years,” she says.

Just one tale of many

The numbers of Tunisians attempting to get into Europe has spiked in recent years, with many sub-Saharan Africans also using Tunisia as a jumping off point to Europe. In 2008, at around 7,000 Tunisian citizens represented the largest group of arrivals at Lampedusa.

Following the 2011 uprising, however, these figures soared with about 20,000 attempting the crossing in the first quarter, according to Frontex, the body charged with securing the EU’s maritime borders.

“I think it was due to the despair in the revolution, because people thought that with the revolution everything was going to be solved quickly,” says Messaoud Romdhani, a director at the Tunisian Forum for Socio-Economic rights (FTDES), which advocates on behalf of migrants and their families and co-sponsored the recent migration conference in Monastir.

Romdhani also notes that borders had lax security at the time, and said that weather in the spring of 2011 was well-suited for making the journey.

In 2011, Italy tried an experiment whereby Tunisians who had arrived between 15 January and 5 April 2011 were a six-month residence permit and freedom to travel across the Schengen Zone. But the policy was quickly spurned by other EU countries with France - Tunisia’s former colonial power - in particular denouncing Italian "laxity".

Europe has since responded by beefing up its Frontex force which has become the main line of defence.

But border control can only ever be a part of the puzzle. European demands that North Africa act as the “guardian of the borders of Europe” is a superficial solution, explains Romdhani

“The partnership between Europe and Tunisia is based most of the time on externalisation of frontiers rather than trying to find a solution, a partnership,” says Romdhani. “This [will not work] without any economic cooperation or trying to find a solution for these people.

“People will continue to go anyway, because now the economic and social situation is in a state of total despair. The number of unemployed is increasing, the number of university graduates is also increasing. Poverty is reaching an alarming state - [it is] a total economic crisis.”

Until a more holistic approach is enacted, Frej and other like him will keep on coming.

Many Tunisians yearn for the freedom to travel and work in Europe which their parents and grandparents had and it is not uncommon to hear tales about migrant workers who travel to Italy and other parts of Europe to help in seasonal work, such as harvest.

Frej says that he regularly meets young men who want to go to Italy. Only once he warns them of his harrowing story do these youngster sometimes begin to reconsider, he says, although some will still likely take their chances over the coming summer months.

Middle East Eye propose une couverture et une analyse indépendantes et incomparables du Moyen-Orient, de l’Afrique du Nord et d’autres régions du monde. Pour en savoir plus sur la reprise de ce contenu et les frais qui s’appliquent, veuillez remplir ce formulaire [en anglais]. Pour en savoir plus sur MEE, cliquez ici [en anglais].