Refugee tide refuses to subside as hundreds land in Lesbos

LESBOS, Greece - They came in their hundreds, despite EU warnings they would be sent back - yet another wave of humanity washed up on the shores of this tiny island in the Aegean.

Fifteen boatloads reached Lesbos on Sunday, all of them from Turkey, with a cargo of more than 800 people joining thousands already here seeking sanctuary and a better life in Europe. Several other boats were stopped by Turkish coastguards as they attempted to reach Greece.

Men, women and children reached the beach soaking from their journeys, clutching meagre possessions, glad to have reached safety where others had died.

And it seemed that an EU deal to send new arrivals back to Turkey, struck last week and in force from midnight on Saturday, did nothing to persuade them otherwise. It may even have encouraged them.

For those now on the island, the task ahead was to reach the Greek mainland before European border officials organised themselves to start enforcing the EU deal.

This weekend, thousands left Lesbos on ferries destined for newly constructed refugee camps in northern Greece, but not everyone was as lucky.

Sitting at Mytilini port, Ahmed Ali waited for his turn as he watched ferries load and unload.

"I wanted to take the ferry to Greece today, but they are full," said the 26-year-old Syrian dentist from Deir Ezzor.

"They can’t send Syrians back to Turkey - it’s wrong. But Greece can’t help us either. My brother is in Germany. He loves it, I have to go there."

No papers, no rights

At Moria refugee camp, where arrivals in Lesbos must now register, several hundred Pakistanis waited to be told of their fate under the new deal - they are not being given registration papers that they need to get on ferries to the mainland.

"The police are closing all the camps, taking people to Kavala but telling us to stay here," said Fesi Ershed, a 22-year-old from Sialkot. "I don’t know what they will do with us."

Gatan, a Syrian who had just arrived with his wife and two children, said he chose to ignore warnings about the EU deal.

"In Turkey they told us not to go to Greece, that we risk arrest," he told the AFP news agency. But he added: "We could not stay in Turkey. We want to go to Germany or France."

Moria camp was cleared over the weekend and many of its residents shipped to the Greek mainland. Many volunteers spoken to by MEE believed it would be transformed into a detention centre in line with the EU deal that would deport "irregular" migrants back to Turkey.

Officials said it would take time to start sending people back, as Greece awaited thousands of European staff needed to take on the daunting task of mass repatriation.

The Athens' coordination committee SOMP, in charge of implementing the EU deal, insisted however that those arriving from Sunday faced certain removal to Turkey.

"They will not be able to leave the islands, and we are awaiting the arrival of international experts who will launch procedures for them to be sent back," the agency said.

The EU deal

Under the EU deal, for every Syrian among those sent back from Greece to Turkey, the EU will resettle one Syrian from the Turkish refugee camps where millions of people are living after fleeing their country's brutal civil war.

The EU will also speed up talks on Ankara's bid to join the 28-nation bloc, double refugee aid to $6.8bn, and give visa-free travel to Turks in Europe's Schengen passport-free zone by June.

The aim is to cut off a route that enabled more than a million people to pour into Europe last year, fleeing conflict and misery in Syria, the wider Middle East and elsewhere.

Realistically, migrants will likely not start being returned to Turkey until 4 April, according to German Chancellor Angela Merkel, a key backer of the scheme.

EU officials have stressed that each application for asylum will be treated individually, with full rights of appeal and proper oversight.

The deal also plans major aid for Greece, a country now struggling not only with a debt crisis but with some 47,500 migrants stranded on its territory.

The EU has said its new plan will stop refugees attempting dangerous Mediterranean crossings which have already killed thousands since the outbreak of the Syrian civil war.

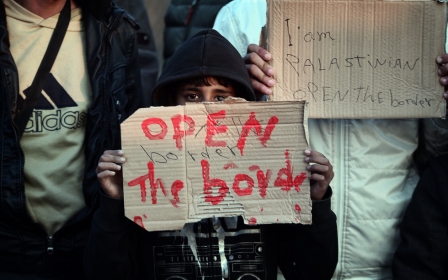

But many believe it marks a closure of borders and reflects growing anti-immigration rhetoric among EU states.

Eastern European countries have refused to accept those who arrive on their borders, building fences, turning back thousands of people and severely restricting entry conditions.

Hungarian Prime Minister Viktor Orban has said refugees threaten Europe’s Christian identity, while Slovakia's Prime Minister Robert Fico recently said his country would "never make a voluntary decision that would lead to formation of a united Muslim community in Slovakia".

Germany, which was praised by rights groups for accepting a million people by the end of 2015, has also apparently shifted its policy and was central to striking the EU-Turkey deal.

Following incidents including a spate of sexual assaults on New Year's Eve in Cologne, anti-immigration parties have pressed Chancellor Merkel to “change course” on the open door policy.

"The federal government has completely changed its refugee policy, even if it does not admit that," Horst Seehofer, leader of the Christian Social Union, the Bavarian sister party to Merkel's Christian Democrats, told Bild am Sonntag.

"There has been a creeping withdrawal from the unconditional welcoming culture. No German politician today says: 'The borders are open, let everyone come to Germany'."

Rights groups have raised concerns about the status of refugees in Turkey.

Turkey has been accused of deporting Syrians back to their home country and abusing some of those allowed to stay. Turkey is also not a full signatory to the UN’s Refugee Convention and does not recognise non-European refugees.

In addition, Turkey’s low-level war with Kurdish militants in the southeast has threatened to destabilise the country further.

Amnesty International called the deal a "historic blow to human rights," and on Saturday thousands of people marched in European cities including London, Athens, Barcelona and Amsterdam in protest.

* Alex MacDonald and the AFP news agency contributed to this report.

Middle East Eye propose une couverture et une analyse indépendantes et incomparables du Moyen-Orient, de l’Afrique du Nord et d’autres régions du monde. Pour en savoir plus sur la reprise de ce contenu et les frais qui s’appliquent, veuillez remplir ce formulaire [en anglais]. Pour en savoir plus sur MEE, cliquez ici [en anglais].