Seven years of death from the air: Who's bombing whom in Syria

It has been seven years since, amid the turmoil of the Arab Spring uprisings, a group of pro-democracy activists were arrested and tortured by Syrian President Bashar al-Assad’s security forces, prompting thousands to protest.

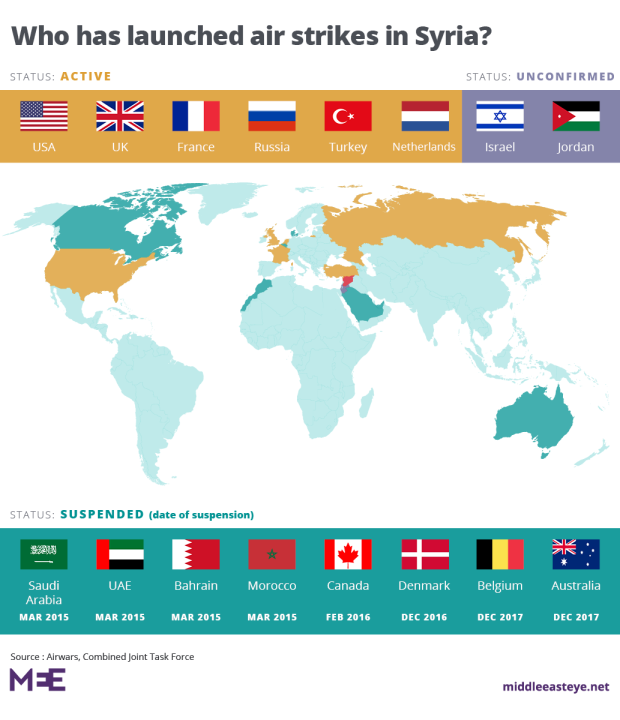

The ensuing crackdown ignited a full-blown civil war, which fuelled the rise of the Islamic State and other militant groups. In a dramatic internationalisation of the conflict, a grand total of 16 countries have since launched military campaigns in Syria, turning the embattled country into a staging ground for a multi-faceted proxy war.

Here’s a look at the competing interests in war-torn Syria, who bombed, and when:

The United States

The US military was the first external force to launch an air war in Syria in September 2014 and American warplanes have been striking Islamic State positions in the country ever since.

Initially its strikes focused on the Syrian-Kurdish city of Kobane and it did not target Assad’s forces or moderate rebel groups in the country, but the US has since conducted strikes against al-Qaeda-linked militants and in April 2017 it launched a massive cruise missile attack on a Syrian government airbase in response to Assad’s forces’ use of chemical weapons.

The US is the lead nation of the International Coalition for Operation Inherent Resolve, the coalition against Islamic State, which officials say is made up of 71 nations. A spokesperson for the coalition declined to “break down” the active members of the coalition or confirm which nations are currently engaged in military operations.

“What we can tell you is that each nation’s contributions are vital to the overall mission,” they told Middle East Eye.

For as long as states seek to destroy militant groups with air power, then civilians will be the ones who will suffer the most; a reality that not only is predictable but is also one that leads to more angry men joining militant groups in revenge

- Iain Overton, executive director at Action on Armed Violence

What is clear, though, is that the US-led coalition has launched more than 15,000 air strikes in Syria and, according to Airwars, led to the deaths of at least 6,136 civilians.

The US has been responsible for the vast majority of coalition air strikes in Syria; Airwars says it was responsible for at least 95 percent of the strikes in Raqqa and dropped at least 21,000 munitions in the battle for the city.

Under the watch of President Donald Trump and Defence Secretary James Mattis, a shift to “annihilation tactics” has reportedly contributed to a dramatic rise in civilian casualties.

“One of the reasons Syria has seen so much harm from air-dropped bombs is that, as well as becoming a battlefield for a much wider global struggle of ideology and geopolitics, it is a place where governments are unwilling to send their own troops to fight, and die, on the ground,” Iain Overton, executive director at Action on Armed Violence, told MEE.

He added: “Air strikes, no matter how framed in terms of precision and accuracy, are - when used in cities and towns - immensely harmful to civilians... For as long as states seek to destroy militant groups with air-power, then civilians will be the ones who will suffer the most; a reality that not only is predictable but is also one that leads to more angry men joining militant groups in revenge.”

Russia

Russia commenced strikes on Syria, in support of Assad, with strikes on Islamic State fighters in Homs, Hama and Latakia provinces in late September 2015. The strikes reportedly came at the request of the Assad government as Moscow states they would target militant groups.

But the US-led coalition quickly expressed concern it was also targeting anti-Assad rebel groups.

Moscow's intervention, after a military build-up in Assad’s coastal heartlands, added another dimension to the already complex web of countries striking Syria, stoking fears of a more deadly regional or international conflict.

No party to have joined the Syrian conflict has done so without killing civilians, but the scale of deaths caused by Russia’s campaign is far higher than that of the coalition. According to Airwars, it has killed at least 11,250 civilians amid claims it has, unlike the coalition, deliberately targeted civilians and the infrastructure of civilian life, including markets, hospitals and homes, especially in the battle for Aleppo in late 2016.

Assad's forces

Air forces loyal to Assad were mostly declared “inoperational” at the start of the conflict and operations were restricted to loyal pilots from the president's Alawite sect.

However, the battle for Aleppo in 2012 saw an all out air war wages by government’s air forces against rebel fighters with tens of thousands of air strikes, including using cargo planes and helicopters pressed into service to drop barrel bombs.

Today Assad’s air force is thought to have been reduced to fewer than 50 combat aircraft, primarily due to combat losses.

France

France was the first nation to join the US in its fight against Islamic State in Syria and Iraq in 2014, and remains the third most active member of the US-led coalition, according to Airwars. Paris launched its first air strike in Syria in late September 2015 after it opened a war crimes investigation against Assad, however strikes have been restricted to Islamic State fighters.

Nonetheless, France has been more forward than any other US ally. It was early in calling for Assad to step down and deployed its only aircraft carrier, Charles De Gaulle, to the region after Islamic State claimed responsibility for militant attacks in Paris and accused France of “striking Muslims in the lands of the caliphate”.

The United Kingdom

The British parliament initially blocked plans to send Royal Air Force (RAF) jets to bomb Assad’s forces over their use of chemical weapons, in what was a dramatic defeat for former Prime Minister David Cameron in August 2013.

However, when the war in Syria came before the House of Commons again in December 2015, MPs approved air strikes against Islamic State militants, expanding a campaign already being waged against the group in Iraq.

The intervention was opposed by Labour Party leader Jeremy Corbyn, but saw an impassioned speech from his then foreign affairs spokesman Hilary Benn, who said: “We are here faced by fascists. Not just their calculated brutality, but their belief that they are superior to every single one of us in this chamber tonight and all of the people we represent. They hold us in contempt.”

Since then, the UK has dropped more than 500 bombs and missiles on Islamic State targets in Syria, as the UK has become the second largest contributor to the US-led coalition. There is no sign that RAF jets and Reaper drones are set to return to the UK anytime soon.

We are here faced by fascists. Not just their calculated brutality, but their belief that they are superior to every single one of us in this chamber tonight and all of the people we represent

- Hilary Benn, Labour MP

In fact, there have been calls for an expansion of the RAF’s role to target government forces from Foreign Secretary Boris Johnson and some Labour backbenchers.

“I refuse to accept that it’s too difficult to intervene to protect civilians,” John Woodcock MP, vice chair of the Friends of Syria parliamentary group, told MEE.

“There is a window for a humanitarian mission across areas currently being terrorised by Assad’s forces. The UK and others could offer to protect those areas and say to Assad and Russia that this is happening, this is where aid is going and you must let them through.”

Woodcock said that “countries with the ability” to intervene have just as much a responsibility to act now, as they did when the conflict started seven years ago.

Calls to expand the UK’s air war in Syria come as ministers in Westminster continue to say there will be “no respite” in strikes and insist that the RAF has caused no civilian casualties in Syria or Iraq, despite an investigation by MEE revealing that British jets have dropped more than 3,400 bombs and missiles since 2014.

Chris Cole, a campaigner for Drone Wars, told MEE: “British air strikes have also dramatically increased in Syria over the last 12 months, yet there is little discussion in parliament or the media about what such strikes are achieving in the long term.”

Israeli strikes

Israel has acknowledged at least 100 air strikes on Syria since 2013, including strikes against military installations, Palestinian militants and Hezbollah fighters, although Tel Aviv largely does not confirm military attacks.

Last month, Israel said it inflicted huge damage on air defences and Iranian targets in Syria after one of its jets was brought down during a raid.

The downing of the jet followed an Iranian drone launch into Israeli territory, it said.

Turkey

A major opponent of the Assad government, Turkey conducted its first strikes against Islamic State in July 2015 after one of its soldiers was killed in an exchange of gunfire across the border.

Turkey is a key Nato member, the US makes heavy use of its Incirlik air base and it is officially part of the US-led coalition fighting Islamic State, but it has been an “ambivalent member” with few strikes being aimed at coalition targets, analysts say.

Instead, it launched a massive assault on Kurdish forces in January, amid warning that it was potentially putting itself in direct conflict with US-backed forces.

Up to 72 jets joined a ground assault on Afrin to “suffocate” the Kurdish-led People’s Protection Units (YPG) after Ankara condemned the US for supporting the group, which has worked alongside allied Arab fighters to drive Islamic State militants from tens of thousands of square kilometres of Syrian territory.

Australia

Canberra agreed to conduct strikes on Islamic State from September 2015 and kicked off its air campaign by targeting armoured vehicles in eastern Syria. Unlike the US, it has not targeted Assad or rebel groups, and in December 2017 it announced it was withdrawing its aircraft and ending its bombing operation.

Canada

Canada launched its first strikes against Islamic State - against positions near Raqqa - from a base in Kuwait in April 2015. However, an election promise by Prime Minister Justin Trudeau saw the country’s air force halt all bombing operations from February 2016. Its six jets were withdrawn that month after conducting 1,344 sorties in total.

Iran's role

Tehran’s antiquated air force has not launched strikes in Syria, but it has made use of armed drones in the conflict. Tehran has also sent military advisers, volunteer militias and, reportedly, hundreds of fighters from its Quds force, the overseas arm of the Iranian Revolutionary Guards Corps (IRGC), to support Syrian government forces.

It has also reported to have supplied thousands of tonnes of weapons and munitions to Assad’s forces and pro-Iranian Hezbollah, which is fighting on Syria’s side.

Denmark

Four Danish F-16s were deployed to the Middle East to strike Islamic State fighters in Syria from August 2016 after a request from the US-led coalition.

The first targets to be hit were militants in and around Raqqa by jets launched from the Incirlik air base in Turkey. Denmark's contribution rose to seven jets by the end of 2016, but was halted in December after suggestions that Danish forces were involved in a series of “unintentional human errors” and killed fighters aligned with the Syrian government instead of Islamic State militants.

By the time the Danish F-16s returned to their home bases, they had flown 547 missions and dropped 504 bombs on Syrian targets.

The Netherlands

The Netherlands agreed to join the US-led coalition in January 2016 with four F-16 jets. The jets were already in operation over Iraq and were redeployed despite the fact that foreign military interventions are especially sensitive in the Netherlands, which led a disastrous UN peacekeeping mission in Bosnia in 1995 during which 8,000 Muslim men and boys were massacred by Serb forces.

However, munitions data suggests that during an early deployment against Islamic State, the Netherlands may have been the fourth most active member of the coalition, after the US, UK and France.

Operations were paused in July 2016 when Dutch F-16s swapped out for Belgian jets. Its latest deployment came in January with the deployment of six F-16 jets from an airbase in Jordan.

Belgium

Belgium joined strikes against Islamic State in the summer of 2014 with six F-16 jets but temporarily suspended strikes in July 2015 citing “unsustainable” financial costs. It now burden shares with the Netherlands, and its most recent deployment of jets came to an end in December 2017. Both countries lurk at the bottom of the Airwars transparency table for coalition members, refusing to say where, when or what they bomb in Syria.

Jordan

Strikes by Jordanian jets started alongside the US in September 2014, but escalated from February 2015 in reaction to the capture and burning alive of a downed Jordanian pilot by Islamic State militants. More recently Jordan’s King Abdullah II has called for a “political solution” to the conflict, but his country’s jets continued to strike Islamic State targets in Syria as recently as February 2017.

Saudi Arabia, UAE and Bahrain

US Central Command announced in September 2014 that Saudi Arabia, UAE and Bahrain had joined the coalition striking Islamic State in Syria, and all three Gulf states deployed small numbers of fighter aircraft.

Along with Jordan, the three states participated in the first night of coalition strikes on Syria, on 23 September 2014. Approximately 135 air strikes were carried out by the Saudis, Jordanians and Emirates before the start of the war in Yemen saw their forces mostly re-deployed.

Morocco

Morocco deployed F-16s jets to the UAE in 2014 to join the US-led coalition against Islamic State. Its first strike was carried out that December, but the country re-focused its efforts on strikes in Yemen from March 2015.

Middle East Eye propose une couverture et une analyse indépendantes et incomparables du Moyen-Orient, de l’Afrique du Nord et d’autres régions du monde. Pour en savoir plus sur la reprise de ce contenu et les frais qui s’appliquent, veuillez remplir ce formulaire [en anglais]. Pour en savoir plus sur MEE, cliquez ici [en anglais].