'Two classes left - rich and poor': Sinking Tunisia’s currency

TUNIS - Mouldi Mohamed Ali, who has run a corner store in the capital for close to a decade, spreads his arms and gestures to the various consumer products lined up against his walls: toothpaste, razors, biscuits, coffee and more.

"Almost 100 percent of what you see, their prices have increased since the new year," he said. "And those whose prices didn't increase, either their quality or their size decreased."

Almost 100 percent of what you see, their prices have increased since the new year

- Mouldi Mohamed Ali, shopkeeper in Tunis

Mouldi pulls out a local-brand chocolate bar which used to be much thicker, he said, rattling off products and their prices increases off the top of his head. His livelihood depends on knowing the prices, after all.

"Eighty percent of people who shop here, when they see the prices going up, they say, 'Ah, those were the days' under Ben Ali. Prices were more stable then. Now things cost double," said Mouldi.

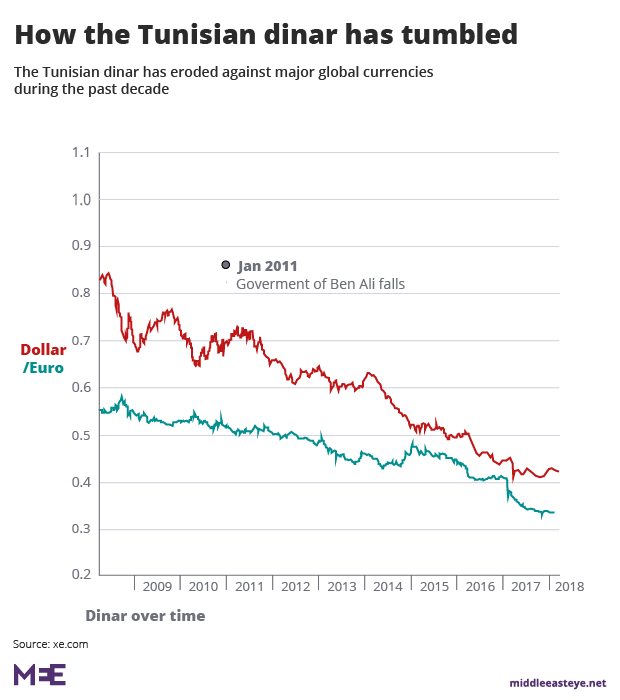

When Tunisia agreed to a four-year, $2.9bn loan with the International Monetary Fund in June 2016, it was still reeling from the shock to its tourism industry following two deadly terrorist attacks the previous year. At the time, the IMF stressed that the dinar was overvalued and had to be weakened in order to boost exports and invigorate the country's economy.

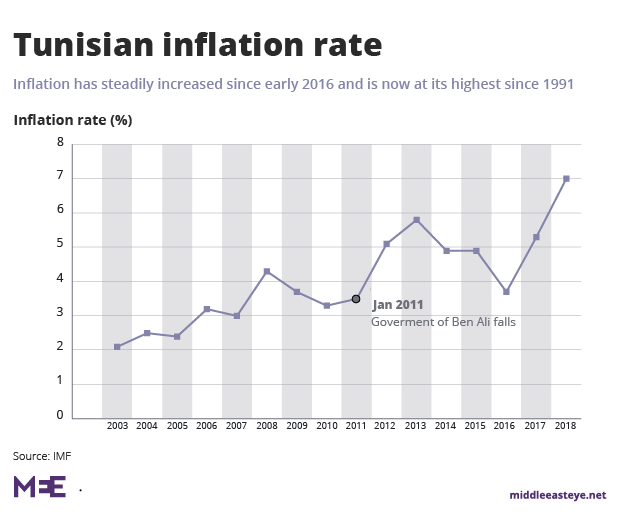

Two years since the deal was signed, Tunisia's currency has lost more than 15 percent of its value against the dollar and more than 23 percent against the euro; inflation reached 7.6 percent this March. Last month, the IMF said the dinar has even further to drop.The fall in the dinar's value - alongside other reforms, including wage freezes and subsidy cuts that are tied to a structural reform programme - is having a major impact on Tunisians. Prices have jumped as importers are forced to pass on their increased costs. Many blame the IMF for their hardships.

"Neither the depreciation of the exchange rate, nor the increasing of the interest rates, will help the Tunisian economy," said Aram Belhadj, assistant economics professor at the University of Carthage.

"The IMF have to understand that some recommendations will not help the people of Tunisia to get out from this difficult situation."

Clash of policies

The IMF has said that a "more flexible exchange rate ... will be instrumental in spurring job creation and supporting Tunisia's export sector, which has already improved in the first three months of this year".

But some Tunisian economists say the policies have actually wreaked havoc, causing inflation to rise and actually widening the trade deficit in a country heavily dependent on consumer product and food imports.

"The primary cause of inflation in Tunisia is the depreciation of the currency," said Belhadj of the University of Carthage.

"The IMF considers that the exchange rate of the dinar is overvalued and we have to let the currency float. This is flawed because Tunisia is a very open economy, so more depreciation of the dinar will cause very high import prices, and Tunisia imports a lot, so the trade balance will be aggravated."

Depreciation hurt Tunisia's trade balance by 1.1bn dinars in 2016 and a further one billion in the first half of 2017, according to Central Bank figures highlighted in an October 2017 report by the Tunisian Observatory of Economy (OTE by its French acronym)."Instead of alleviating trade deficits as expected by the IMF, the depreciation of the dinar has conversely increased it," Chafik Ben Rouine, co-founder and president of OTE, wrote.

Ben Rouine has also documented how IMF forecasts of the value of the dinar brought its worth down all on their own.

"Reviews after reviews, IMF constantly estimates an overvaluation of 10 percent. This estimation was used to put more pressure on the [Central Bank of Tunisia] in order to push it to consent to the drop of the value of the dinar," he wrote.

"When the dinar reaches the value desired by the IMF, the IMF comes up with a new forecast through which it estimates that the dinar must drop by 10 percent once more, and so on."

One person feeling the squeeze is Mokhtar M'Hiri. The chief financial officer at Toupack Group, a packaging company that imports machinery and raw materials and sells them on domestically, told MEE that his company has been forced to triple prices in some cases as a result of the depreciation.

One item that has been particularly pricey are boxes for a potato-chips manufacturer.

"We started selling the box two years ago. It was 0.6 dinars and today it's three times," or 1.8 dinars, he said. "So for him [the client], it's a very big part of the cost of his product."

The IMF concedes that inflation is partly fuelled by dinar depreciation and that Tunisians will feel the pinch.

But it has also suggested that the burden of the country's structural adjustment programme should be shared and actions should be taken to protect the "most vulnerable in society," including maintaining VAT exemptions and subsidies on basic food items.

'A very important signal'

Depreciation of the currency might seem like a technical issue, but the effects are all too real for ordinary Tunisians, whose wages aren't going up as prices increase and the power of the dinar tumbles.

At the beginning of the year, there was a swelling of spontaneous nationwide protests as a new budget law, authorising price increases and subsidy cuts, went into effect.

The favourable opinion of the IMF ... it gives a very important signal to the financial markets

- Taoufik Rajhi, state secretary of major reforms

Amid the unrest in early January, a hashtag protest movement called "Fech Nstannew?" or "What are we waiting for?" mobilised to repeal the law.

At that time, Ben Rouine's colleague and co-founder of OTE, Jihen Chandoul, wrote a widely shared opinion piece in the Guardian which argued that the IMF was playing a key role in Tunisia's austerity policies that went beyond depreciation and their effects on Tunisians.

"An escape from the submissions to the IMF, which has brought Tunisia to its knees and strangled the economy, is a prerequisite to bring about any real change," Chandoul wrote.

Some close to the policymakers in Tunisia said the government could have used the op-ed, published after major protests across the country, as a bargaining chip in negotiations with the IMF, but failed to do so.

While unions have been ready to criticise the IMF, the Tunisian government has stressed that it needs to be on the IMF's good side.

The IMF does not advocate austerity. We advocate well-designed, well-implemented, socially balanced reforms

- IMF statement in January

"The role of the IMF is very important for the rest of the international donors. It plays the role of country-rating agency for the rest of [Tunisia’s] donors ... This explains why Tunisia still wants to have the IMF on its side," the state secretary of major reforms at the prime ministry, Taoufik Rajhi, said in an interview this March.

"Not to mention that with the favourable opinion of the IMF ... it gives a very important signal to the financial markets, demonstrating that Tunisia is on a good trajectory for investors."

'Only two classes'

Some observers say the current situation in Tunisia shows the policymakers are caught between competing and contradictory development and trade policies.

"On the one hand, for very basic things - cereal, oil, milk, sugar - you have to protect the price of the Tunisian consumers. On the other hand, they believe in export-led growth," said Max Ajl, a doctoral researcher at Cornell University focused on Tunisia's political economy.

"And on the third hand, they believe in devaluation. And they believe in all these things simultaneously."

The result, he said, is a policy that exports the impacts of devaluation onto the working class.

"What the government is doing is effectively raising the inflation rate without raising wages for the taxi drivers, for example," he said.

"So what happens is that ... through devaluation, all kinds of purchasing goods will get more expensive given Tunisia's reliance on imports for a lot of the consumption basket."

The faith in specifically export-led growth by Tunisian policymakers comes from what Ajl calls "an ideological vacuum". With no alternative developmental models, many key Tunisian officials "accept the international financial institutions notion that devaluation is going to be helpful for Tunisian exports".

One alternative, which some scholars have suggested, would be to create jobs and raise salaries to get the economy rolling again. But Ajl said that is unlikely to be popular with Tunisian companies. "Capitalists never want to do that. They do it only under massive pressure usually," Ajl said.

In 2010, Tunisia used to have three social classes. Fifteen percent poor, 15 percent rich, and 70 percent middle class

- Mouldi Mohamed Ali, shopkeeper in Tunis

Meanwhile, pressure is building as austerity measures continue to ratchet up. According to the Tunisian Forum for Economic and Social Rights, a local NGO that conducts research and advocacy, 2,465 protests occurred across Tunisia over January and February alone, a plurality of them over economic and social issues and most of them over public services.

"Before, in 2010, Tunisia used to have three social classes. Fifteen percent poor, 15 percent rich, and 70 percent middle class, who could buy meat even twice a week," said Mouldi, the shopkeeper.

"Now there's only two classes: poor and rich ... the situation in the country is disastrous."

Middle East Eye propose une couverture et une analyse indépendantes et incomparables du Moyen-Orient, de l’Afrique du Nord et d’autres régions du monde. Pour en savoir plus sur la reprise de ce contenu et les frais qui s’appliquent, veuillez remplir ce formulaire [en anglais]. Pour en savoir plus sur MEE, cliquez ici [en anglais].