Mosul's desecrated museum: 'IS smashed up our history'

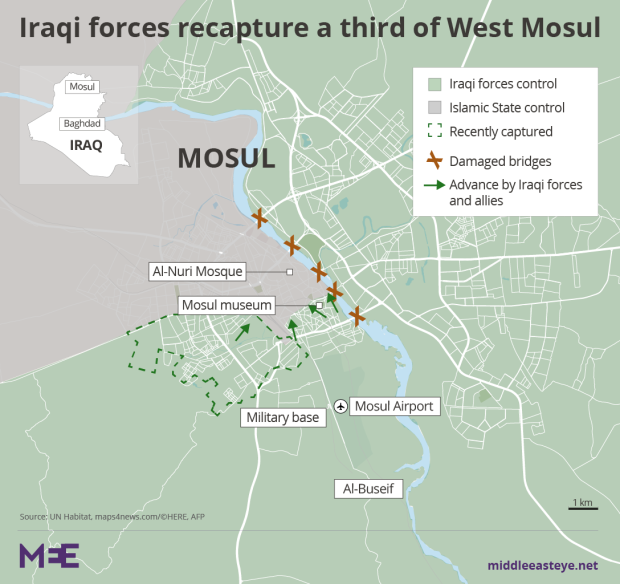

MOSUL, Iraq - Lying just inside the front lines against the Islamic State, the newly liberated Mosul Museum can only be reached by clambering across the roof of the city's courthouse, flattened by a coalition air strike, and sprinting across a road still under threat from IS snipers.

Clambering through a narrow side window beside the locked wooden doors, inside, the museum stretches out as a vast dust-coated emptiness. The rubble of thousands of years of history still lie beneath displays from which every exhibit has been ripped.

IS militants released a video in February 2015 showing themselves destroying ancient Assyrian and Hatrene artefacts in the museum with sledgehammers and pneumatic drills.

Daesh made that video of themselves smashing up our history. They have destroyed everything

- Abdul Emir al-Mohamed Alwi, historian

In the footage, a militant decried the ancient treasures as idols worshipped by pre-Islamic peoples, claiming their assault followed instructions issued by the Prophet Muhammad to destroy such idols in newly-conquered lands.

Despite claiming religious legitimacy for the widely-publicised destruction, IS members appear to have looted hundreds of other historic items from the museum. Soldiers say these would have been smuggled out of Iraq and sold on the lucrative European black market for antiquities, helping to fund further IS activities and operations.

Artefacts in the museum, formerly the second largest in Iraq, had charted the thousands of years of regional history, including the multiple invasions the country has endured.

"Mosul has been taken 21 times in the course of history and every successive invader has taken control with very little fighting," said lieutenant colonel Abdul Emir al-Mohamed Alwi, also a historian.

"The last one was Daesh and, as with the invasions in the centuries before, the citizens of Mosul just handed them the keys to the city. And look what happened!"

When he stepped into the gallery formerly filled with Assyrian artefacts dating back thousands of years, his shoulders sagged. Shaking his head in despair, Alwi sat down heavily on a podium where one of those statues once stood.

"This was the Assyrian room, where Daesh made that video of themselves smashing up our history. They have destroyed everything."

Only parts of the museum's collection were shown in the 2015 video, but the recent liberation of the area has dashed archaeologists' long-held hopes that other artefacts might have escaped unharmed.

Today, only a single museum piece remains in tact; a decorative wooden chest, richly-carved with a verse from the Quran in Arabic script.

Standing in what was formerly the Islamic Hall - one of four galleries, each dedicated to a separate era of Iraq's rich history - the chest only sustained damage to its lid, half of which has been caved in. But the displays for Islamic artworks behind the chest have been stripped of their exhibits.

"When I climbed through that window today, my heart clenched and I started weeping," admits Mosul resident Suhaib, 33, one of the first journalists to enter the museum after its liberation. "This is my city, this is my country and this was our history."

"A giant statue of a winged bull with the head of a man stood right there," he says, pointing to an empty wall. On the floor beneath is a heap of rubble - all that remains of a sculpture of the protective mythological figure of the Lamassu, the destruction of which also featured in the IS video.

Some of the chunks of rubble show the relief work of feathered wings from the Lamassu. Two of the beast's paws have survived the desecration, beside which lies the finned tail of a mortar round. "It was the biggest and nicest thing in the museum," Suhaib says. "There used to be two but the Americans took one away in 2004 and sold it somewhere in Europe. That was the last one we had left."

A pile of instructions for correct Islamic bedtime prayer rituals, printed on green paper bearing the IS logo, lie on one unrecognisable chunk of a Lamassu.

Suhaib managed to escape from Mosul a year after IS seized control of the city, on his second attempt. Colleagues at the local TV station where had he worked, a stone's throw from the Museum, were amongst tens of journalists abducted shortly after IS arrived and, fearing for his life, he tried to sneak out of the city.

The IS militants who caught Suhaib punished him by smashing in his front teeth and pistol-whipping him around the face, the scars from which are still visible.

He then spent a year in hiding, biding his time until he could make another attempt to escape.

When a coalition air strike hit his neighbourhood in 2015, throwing IS fighters into a state of confusion, Suhaib managed to slip out of the city unnoticed.

His parents remain trapped inside IS-occupied west Mosul and, although he kept in touch with them via a forbidden mobile phone they kept hidden in their house on pain of death, he has not been able to speak to them for more than a fortnight.

The museum's extensive storerooms for the safe-keeping of additional historic objects had also been looted.

One blackened basement storeroom stands empty, illuminated by sunlight from a segment of wall blown out by an air strike.

The only thing to have survived a blaze ignited by the air strike is a metal exercise bike, the charred frame of which stands in a corner, indicating that IS militants used the room as their personal gym.

"This was where artefacts not currently on display were stored. I remember last time I was here, maybe five years ago, it was full of valuable historical items," said Alwi. "Everything has been stolen, everything, and I doubt these things will ever be recovered."

As soldiers scoured other basement areas, which have not yet been checked for unexploded ordinance or IEDs, a cry of delight emanated from beneath the floor of the museum, heralding the discovery of a salvaged item.

Everything has been stolen, everything, and I doubt these things will ever be recovered

- Abdul Emir al-Mohamed Alwi, historian

Iraqi soldier Ashraf climbed out of a gaping hole blown open in the floor of the museum, carrying on his back a framed illustration of Mosul's Nouri mosque.

Once famous for its unusual leaning minaret, in recent years it gained notoriety for having been the location where self-proclaimed IS "caliph" Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi announced the establishment of a 21st century Islamic State.

After wiping the picture clean, Ashraf slings it onto his back and heads out into the sniper fire, climbing through a hole IS fighters smashed through the wall of the museum, to enable themselves to move quickly and inconspicuously between buildings.

After seizing control of Mosul, IS destroyed numerous historic sites, as well as churches and mosques. One of the most serious losses in east Mosul, liberated by Iraqi armed forces earlier this year, was the Nabi Younis mosque, purportedly built around the tomb of the shared Christian and Muslim prophet Jonah (Younis in Arabic).

When Iraqi forces entered IS tunnels beneath the mosque, blown up with explosives in 2014, they discovered a historical gem - a previously undiscovered ancient palace. With the hillside around the palace deemed dangerously unstable, archaeologists have not yet been able to explore the valuable find.

This article is available in French on Middle East Eye French edition.

Middle East Eye propose une couverture et une analyse indépendantes et incomparables du Moyen-Orient, de l’Afrique du Nord et d’autres régions du monde. Pour en savoir plus sur la reprise de ce contenu et les frais qui s’appliquent, veuillez remplir ce formulaire [en anglais]. Pour en savoir plus sur MEE, cliquez ici [en anglais].