Tunisian youth hold on to dreams of revolution despite lack of jobs

Buoyed by the 2011 revolution that brought down long-time president Zine El Abidine Ben Ali, 30-year-old engineer Ali Chimi el-Mekki decided to quit his well-paying job in Paris and return to Tunisia.

Like so many other young people, Mekki left home to study abroad because he felt that there were not enough opportunities in Tunisia, but the revolution changed that.

Five years to the day since the former strongman was toppled, however, Mekki says that “things have not really moved".

"In Tunisia, there are galling things which are happening in the political, economic and security spheres. There is a certain level of disenchantment regarding 2011. Tunisia still has to get out of the stagnation suffered under the 23 years of the Ben Ali regime,” he told Middle East Eye.

Tunisia’s disaffected youth were a key driving force behind the revolution. When 26-year-old fruit seller Mohamed Bouazizi set himself on fire to protest injustice at the hands of the authorities on 17 December 2010 in Sidi Bouzid, it was the country’s youth who rose up and refused to bow down until Ben Ali stepped down and the promise of a new era had begun. Yet, five years later, the youth is no better off.

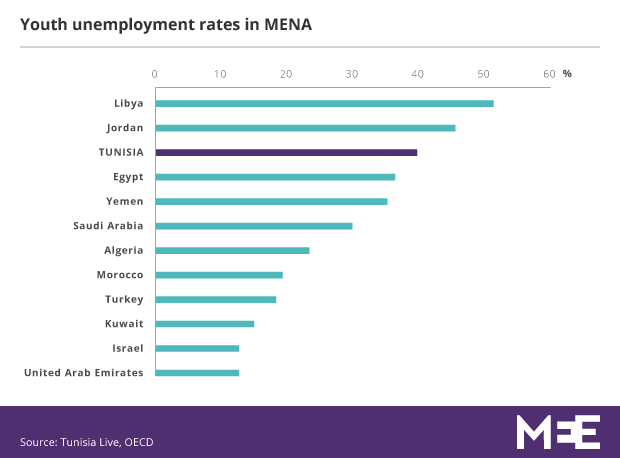

According to a 2015 Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) a "true social tragedy" is happening in Tunisia, with 40 percent of Tunisians under the age of 35 are unemployed and actively seeking work.

The figure does not include those in education, training and those not seeking work. Many of those deemed employed are also under-employed and work less than they would like or have been forced to take jobs in less-skilled sectors due to a lack of high-paying jobs.

Since the revolution, anaemic economic growth, weak job creation and a growing security threat have all worked to undermine the aspirations of Tunisians.

The difficulty of accessing the job market has also had political ramifications and has been blamed for a low level of participation in public life.

While turnout for the 2014 presidential vote was estimated at around 68 percent, young voters largely failed to show up, blaming political parties for hijacking the revolutionary movement.

But while there is ample cause for optimism, many continue to feel that the revolution is not dead and that change will come eventually.

Despite the challenges, Mekki says he still believes in the revolution and is determined to do what it takes to make his web and mobile application development firm succeed in the difficult climate.

"I am one of those who wanted this change and I am still convinced by this Revolution. The messages and ideas which have been transmitted from 17 December 2010 to 14 January 2011 are still relevant. I believe that the Tunisian Revolution is not yet over,” he said.

Activist Tareq Toukabri believes that the change has to first happen at a more grassroots level before radiating upward.

Toukabri set up an organisation Houmetna ("Our district") along with some friends in the town of Majaz el-Bab, a city of 20,000 residents located in the Governate of Beja, just southwest of the capital Tunis.

The group hopes to re-motivate young people in the city by engaging them in different parts of daily life. Houmetna says that its methods, which push young people to voice concerns about issues like exclusion, unemployment or violence, are slowly beginning to have results.

"We want to change mentalities so that they stop expecting the answer to always come from the state. They should take things in their own hands," Tareq told Middle East Eye.

"The educational sector is one of the most affected by the former regime of Ben Ali. We are combating the negativity of young people by encouraging and inviting them to reflect on their potential through dialogue."

Houmetna was particularly active during the October 2014 legislative elections, which saw an increase in violence in political discourse.

"Before this, we had the secular/religious divide. With the elections, political debate has consolidated divisions,” he said. “We have brought together members of various parties, workers' unions and students to create dialogue. It is Tunisia which matters!"

The group now plans to do the same for the local elections slated to take place later this year, and hopes that it will have even more success this time around.

"Young people were not present during the previous elections. This time, we want them to be involved,” he said.

Youth-oriented businesses flourish

For decades under Ben Ali, many felt that Tunisia’s economy was being mismanaged and its middle class undermined by corruption and state heavy-handedness. New shops and enterprises would be set up, but any larger businesses needed to be run in cooperation with the ruling family.

Since Ben Ali’s fall, however, some rules have been relaxed and state corruption and intervention have become less blatant. As a result lots of businesses aimed at Tunisia’s large youthful population have sprung up in towns and provinces alike and there has been a mushrooming of culture cafes, co-working areas, and blogging networks.

"Tunisia is well-placed to become a regional champion in innovation and entrepreneurship if it recognises the potential of young people aspiring to become entrepreneurs," the World Bank said in a report issued before the revolution.

Many young people are well educated, speak more than one language and have shown a willingness to branch out. Despite the difficulties in getting funding, one in 10 young people have launched a small business since the revolution, employing between one and 10 people.

This new-found dynamism, coupled with the relaxation of freedom of speech and freedom of association since the revolution, has breathed a new lease of life into the country, even prompting some emigres, like Mekki, to return home.

Able to dream again

Ghofran Ounissi, a young political analyst for the Jasmine Foundation, a Tunisian think tank dedicated to monitoring political and democratic freedoms in the country, says that the revolution allowed her to dream of a life back in Tunisia – something she didn’t think would ever happen.

“For me, the Revolution was the end of a forced exile, the opportunity to replant roots which had been ripped out," she told MEE. "Naturally, the reality was much more complex. Beyond the collective euphoria, we realised the scale of the damage and the amount of work awaiting the Tunisian people to complete the dream".

According to Ounissi, transitional justice is the main challenge facing post-revolution Tunisia with not enough being done to expose human rights breaches committed under Ben Ali.

"It is the most ambitious and most fundamental work in the next five years in Tunisia,” she said. “Unfortunately, we can only observe that the issue is of little interest to Tunisians. There is, however, the possibility of turning the page of the former dictatorship, and laying the foundations of a society without stigma inherited from decades of repression and a closed society."

Other issues are also causing deep tensions. The new constitution guarantees fundamental rights, but the institutions that monitor there are not yet operational, such as the Constitutional Court, and there have been many human rights breaches.

In recent months, there have been many cases of police abuse, torture and arbitrary arrests targeting mostly young people, including many artists. In late December, a young 17-year-old student, was arrested for things he wrote on Facebook.

Yet many young Tunisians are refusing to give up hope.

Samah, now 26, became an activist during the revolution when she discovered videos of young people being killed by police officers in Kasserine.

"Today, and with hindsight, the ‘revolution’ is still a miracle,” she said. “When I was small, I believed Ben Ali was immortal, that we would always live in the same way.”

She still believes that the "moment of grace [the revolution] has changed, albeit marginally, the relationship between citizens, the state and authorities.

“Today's youngsters still struggle with hierarchy, the image of a father and rhetoric, which have been inherited from the former regime, [but] the definition of politics is changing for young people,” she said.

“They no longer want talk, they want actions. But how can you become an entrepreneur in a country where the most basic individual freedoms are threatened? Where people go to prison for smoking a joint or being with a partner. Old people, who are so keen on absolute control, are afraid of this overflowing energy and new vision."

A version of this article was originally published on Middle East Eye's French page.

Middle East Eye propose une couverture et une analyse indépendantes et incomparables du Moyen-Orient, de l’Afrique du Nord et d’autres régions du monde. Pour en savoir plus sur la reprise de ce contenu et les frais qui s’appliquent, veuillez remplir ce formulaire [en anglais]. Pour en savoir plus sur MEE, cliquez ici [en anglais].